8th Tactical Bomb Squadron

(1964-1969) |

Acknowledgment: B-57B: Special thanks to Joe Baugher sites for its detailed information on the B-57B in Vietnam. Special thanks to Marquis Witt and his B-57 Canberra.org site for its exceptional materials dealing with the B-57B. (Special thanks

for the Doom Pussy story by Bob Galbreath; The Guns of Tchepone story by Larry Mason, Jere Joyner, Bob Mikesh, and Joe Rup, Jr. and weapons

loader narratives by Dan English.) Special thanks to Gene Bonham for his photos and narratives on the B-57s at Phan Rang. A-37B: We are extremely grateful to A-37 Association website for its stories and photos. Thanks to Dennis Selvig for his A-37 anecdotes. Thanks to Richard Dutcher and James Lamb for their

photos on the A-37 Association website. Thanks to the AGE Ranger site (Darryl W. Clark, CMSgt, USAF) for its photos of the 8th AGE Shop at Bien

Hoa. Thanks to Wavelen Wayne Fielder at Det 6 600th Photographic Squadron for his photos of Bien Hoa (APPROVAL PENDING). Other sources include: Air War College: 25th ID After Action Report; Easter Offensive: by W. R. Baker; Paper: They were Good Ol' Boys; VNAF.net,. Lastly we are deeply indebted to the historical information found at Air Force Historical Research Agency (AFHRA) on line.  8th Bomb Squadron insignia 8th Bomb Squadron insignia

Approved June 21, 1954 (KE 8387)

B-57s to Vietnam: The following is from Historical Text Archive: Don Mabry: President Kennedy decided to stand behind Diem. He sent more military advisers

and Special Forces to the country. And the economic support increased

dramatically. By 1963, there were 16,700 advisers in South Vietnam. Although

these advisers were not supposed to engage in combat but some did. The US and

the South Vietnamese army adopted the strategic hamlet program, an effort to

beat the guerrillas by destroying villages which supposedly harbored them. In

addition, Diem attacked Buddhists who opposed his anti-Buddhist repression.

Some responded by immolating themselves to draw world attention. The US began

to think about withdrawing it support of Diem. There were indications that he

might negotiate a peace with North Vietnam. When South Vietnamese generals

began talking of overthrowing him, the US did not demur. He was overthrown and

murdered in November, 1963. It wasn't long before the new government was also

overthrown.

Lyndon Baines Johnson, who became President when Kennedy was murdered,

increased support for South Vietnam, for he saw US honor at stake. In early

1964, the Vietcong controlled almost half of the country. The US began a secret

bombing campaign in Laos in an effort to destroy Vietcong supply roots. On

August 2, 1964, the warship the U.S.S. Maddox was attacked. Then on August 4th,

the Maddox and another destroyer moved into North Vietnamese territorial waters

in the gulf of Tonkin, a violation of international law and an act of war. They

were fired on. Johnson, however, hid the truth and reported to Congress that

the incident constituted an attack on the United States. Congress by a vote of

466-0 in the House and 88-2 in the Senate passed the Gulf of Tonkin resolution

on August 7th, gaining the President of the United States the right to respond

to attacks as he saw fit. This was the legal basis for the Vietnam War. When

Congress repealed the resolution in 1970, the US continued to fight the war.

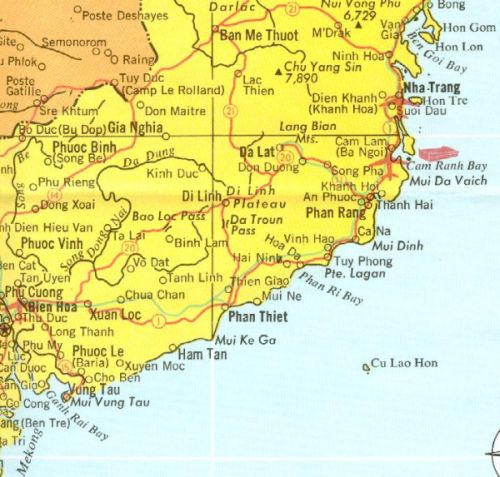

1968 Map of Vietnam & Chronological History (1964-1960)

Bien Hoa and Phan Rang Location in Vietnam (1968 Map)

- 1964

- Aug. 2: U.S. destroyer Maddox reports attack by North Vietnamese patrol boats

in Gulf of Tonkin.

- Aug. 4: U.S. destroyer Turner Joy reports attack.

- Aug. 7: Congress passes Gulf of Tonkin resolution, giving Johnson broad

authority to conduct war.

- Nov. 1: Viet Cong attack Bien Hoa Air Base, destroying six B-57 bombers.

- 1965

- March 8-9: First American combat troops land in Vietnam.

- April 6: Johnson authorizes use of U.S. ground combat troops for offensive

operations.

- April 7: Johnson offers North Vietnam aid in exchange for peace.

- April 8: North Vietnam rejects offer.

- April 17: Students for a Democratic Society sponsor anti-war rally in

Washington.

- Oct. 15-16: Anti-war protests held in about 40 cities.

- Nov. 14-16: First major engagement between U.S. and North Vietnamese forces.

- Dec. 25: Johnson suspends bombing of North Vietnam to push for negotiations.

- 1966

- Jan. 19: Johnson asks Congress for $12.8 billion more for the war.

- Jan. 31: Bombing of North Vietnam resumes.

- May 1: U.S. forces shell communist targets in Cambodia.

- June 29: Johnson orders bombing of oil installations at Haiphong and Hanoi.

- Sept. 23: U.S. military says it uses defoliants to destroy communist cover.

- Oct. 26: Johnson visits troops in Vietnam.

- 1967

- Feb. 22: Operation Junction City, largest operation in Vietnam to date, begins.

- April 15: 100,000 war protesters rally in New York; 20,000 in San Francisco.

- May 19: U.S. planes bomb power plant in Hanoi.

- Sept. 3: Nguyen Van Thieu elected president of South Vietnam.

- Sept. 29: Johnson modifies position, saying the United States will stop bombing

if negotiations begin.

- Oct. 21: "March on the Pentagon" by tens of thousands of anti-war

demonstrators.

- October: U.S. public opinion on war shifts; polls say more Americans now oppose

Johnson's policies in Vietnam than support them.

- 1968

- Jan. 30: Viet Cong and North Vietnamese mount major offensives, catching South

Vietnamese Army offguard, celebrating Tet, the new year holiday.

- Jan. 31: Attack on U.S. embassy in Saigon repulsed. North Vietnamese capture

Hue.

- Feb. 10-17: U.S. casualties set a one-week record 543 killed in action.

- March 16: My Lai massacre of Vietnamese civilians by U.S. servicemen.

- March 31: Johnson announces de-escalation, says he will not run for

re-election.

- April 26: 200,000 demonstrate in New York City.

- May 12: Peace talks begin in Paris.

- Aug. 28: Anti-war protests and riots at Democratic National Convention in

Chicago.

- Oct. 31: Johnson halts bombing.

- 1969

- March: President Nixon announces "Vietnamization" plan to withdraw U.S. troops,

shore up South Vietnamese defenses.

- April 30: U.S. military personnel in Vietnam peak at 543,400.

- May 14: Nixon peace plan proposes mutual troop withdrawal.

- June 8: Nixon announces withdrawal of 25,000 troops.

- Oct. 15: National "moratorium" anti-war demonstrations attract huge crowds

across nation.

- Dec. 1: First draft lottery since 1942 is held.

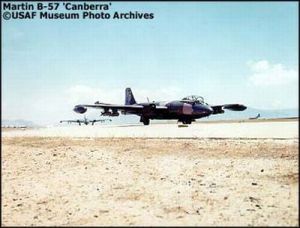

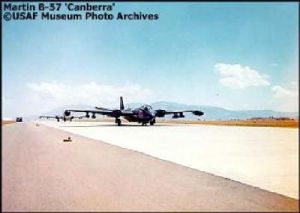

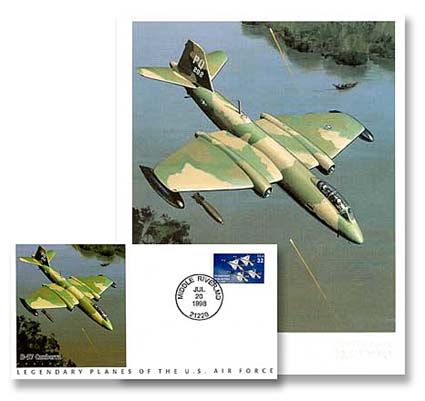

B-57B History

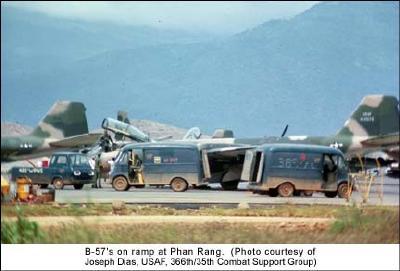

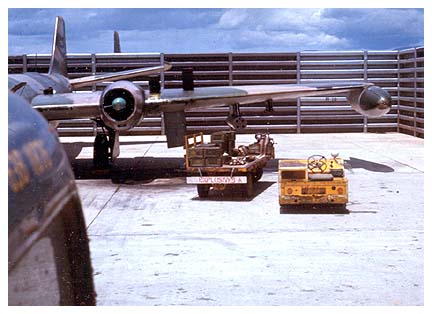

Aircraft 567 and 898 at Phan Rang (Bob Mikesh)

Note the "PQ" tail code of the 8th TBS and "PV" of the 13th TBS.

The following writeup of the B-57B is from Baugher site:

This would ordinarily have been the end of the service of the B-57B with the

USAF, with the 3rd BG being inactivated and all its planes being transferred to

the Air National Guard. However, the worsening situation in Indochina led to orders for the 8th and

13th Bomb Squadrons of the 3rd BG to deploy to Clark AFB in the Philippines for

possible action in Vietnam. As it happened, this move did not take place until August 5, following the

Gulf of Tonkin incident in which North Vietnamese gunboats clashed with US

destroyers.

According to the initial plan, 20 B-57Bs of the 8th and 13th BS were to be

deployed to the Bien Hoa air base near Saigon. This would mark the first

deployment of jet combat aircraft to Vietnam. This was technically a violation

of the Geneva Protocols which forbade the introduction of jet combat aircraft

to Vietnam, but the Gulf of Tonkin resolution which had just been passed by

Congress was taken as a pretext to remove all such restrictions.

The initial deployment to Vietnam got off on the wrong foot. The first two

B-57Bs to land collided with each other on the ground and blocked the runway at

Bien Hoa, forcing the rest of the flight to divert to Tan Son Nhut Airport on

the other side of Saigon. One of the B-57Bs dived into the ground during

approach at Tan Son Nhut and was destroyed, killing both crew members.

During the next few weeks, more B-57Bs were moved from Clark AFB to Bien Hoa to

make good these losses and to reinforce the original deployment. Things got so crowded at Bien Hoa at that time that some of the B-57s had to be

sent back to Clark AFB. Initially, the B-57Bs were not cleared for actual

combat missions, the aircraft being restricted to unarmed reconnaissance

missions that were mainly designed to boost the morale of the population.

However, actual combat was not to be delayed very long. On November 1, 1964,

Viet Cong squads shelled the airfield at Bien Hoa with mortars, destroying five

of the B-57s parked there and damaging 15 others. Further Viet Cong mortar

attacks led General William Westmoreland on February 19, 1965 to release B-57Bs

for combat operations. The first such mission took place on that same day, a strike against suspected

Viet Cong guerrillas near Bien Gia, about 30 miles east of Saigon. This strike

was, incidentally, the first time that live ordnance had been delivered against

an enemy from a USAF jet bomber.

The B-57Bs hit North Vietnamese territory for the first time on March 2, some

25 miles north of the DMZ. This was the first of a series of interdiction

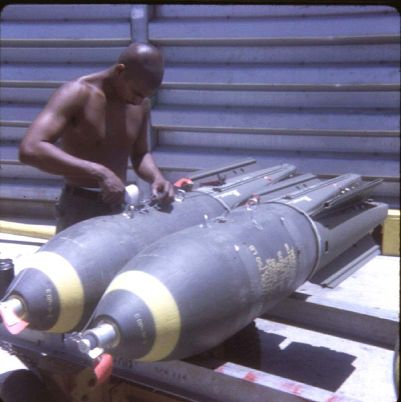

strikes that came to be known as Rolling Thunder. The usual bomb load on these operations was nine 500-lb bombs carried in the

main weapons bay and four 750-lb bombs on the underwing pylons.

In April of 1965, B-57B crews began night interdiction strikes against enemy

supply lines along the Ho Chi Min Trail. Operations were carried out in cooperation with C-130 or C-123 flare-deploying

aircraft that illuminated potential targets and with USMC EF-10B Skyknight

electronics warfare aircraft that jammed radar-controlled AAA and detected

enemy missile sites that were preparing to launch. Eventually these night

interdiction missions extended into North Vietnam, the first such attack taking

place on April 21, 1965. However, it was considered too dangerous to fly C-130

flare-deploying aircraft into North Vietnamese airspace, so each B-57B carried

a set of MK-24 flares in addition to bombs.

On May 16, 1965, while waiting to takeoff on a mission, a B-57B exploded on the

ground at Bien Hoa, setting off a whole chain of secondary explosions. The

resulting conflagration destroyed ten B-57s, eleven VNAF A-1H Skyraiders, and a

US Navy F-8 Crusader. The surviving B-57s were transferred to Tan Son Nhut and

continued to fly sorties on a reduced scale until the losses could be made good. Some B-57Bs had to be transferred to Vietnam from the Air National Guard, and

12 B-57Es had to be withdrawn from target-towing duties and reconfigured as

bombers to make good these losses.

In June of 1965, the 3rd Bomb Group moved to Da Nang to carry out night

interdiction operations over North Vietnam and Laos. Principal targets were

trucks, storage and bivouac areas, bridges, buildings and AAA sites. When deployed at Da Nang, the 8th and 13th Squadrons came under operational

control of the 6252nd Tactical Fighter Wing which became the 35th TFW about a

year later.

Combat attrition in the B-57 force plus the increasing availability of higher

performance fighters to carry out the air war against the North caused the 3rd

BG to be withdrawn from operations against the North in October of 1966 and

relocated to Phan Rang, just south of Nha Trang and Cam Ranh Bay. However, it

appears that B-57 night missions over North Vietnam did continue until at least

Oct 1967. It carried out attacks against Communist forces in the Central

Highlands and supported US ground troops in the so-called "Iron Triangle".

While there, the B-57s operated alongside the Canberra B. Mk. 20s of No. 2

Squadron of the Royal Australian Air Force.

In January of 1968, the 13th Bomb Squadron was deactivated, and the 8th BS was

left in permanent residence at Phan Rang. The main emphasis was again on night

interdictions against the Ho Chi Minh Trail. By July of 1969, the 8th BS's

strength was down to only 9 aircraft, and it was decided that it was time to

retire the B-57B from active service. The surviving aircraft were sent back to

the USA in September and October and put into storage at Davis-Monthan AFB. The

identity of the 8th BS was transferred to another unit at Bien Hoa to become

the 8th Attack Squadron, which was equipped with Cessna A-37s.

Article "On Strike Mission with B-57...the Weapon Reds Fear Most" from "The Buffalo Evening News," Buffalo, NY. in 1965.

(Courtesy Norman Hartman) Out of the 94 B-57s that were assigned to the Southeast Asia theatre, 51 were

lost in combat (including 15 destroyed on the ground). 11 were withdrawn early

to support the B-57G program.  8th TBS Bomber configuration: photo- Mark Witt 8th TBS Bomber configuration: photo- Mark Witt

Note: PQ Tail Code of 8th TBS

(Courtesy Marquis Witt www.b-57canberra.org)Top L: Four napalm under the wing; Top R: Loading napalm

Bottom L: Maintenance Bottom R: Pilot view of bomb sight.

According to Canberra.org: B-57 in Vietnam, The Mission

During the Vietnam War, the B-57 was chosen as the first jet aircraft to strike

North Vietnam. Its long range and loiter capability with a large payload made

it the logical choice as the "Night Intruder" for interdiction on the Ho Chi

Minh Trail. The use of fire bombs, hard bombs up to 1000 pounds, 20 millimeter

and 50 caliber guns made the B-57 a formidable weapons delivery system against

the transfer of supplies through Laos and Cambodia into South Vietnam. With the

aid of C-130's, OV-10's and Ov-2 aircraft as Forward Air Controllers (FAC), the

B-57 was the most effective system used against transporting war goods into

South Vietnam through Laos and Cambodia.

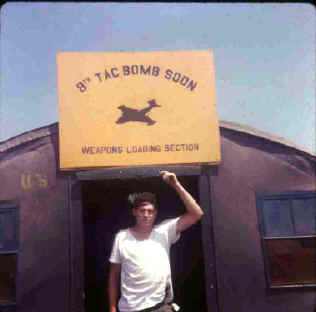

The Eighth and Thirteenth Tactical Bomb Squadrons (8TBS, 13TBS) stationed at

Clark Air Base, Philippines initially launched sorties from Bien Hoa. Later,

Danang Air Base near the DMZ became the base of operations. The final station

was Phan Rang (Happy Valley) where the 8TBS, as the oldest continuously

operating bomb squadron in the Air Force (World War I), continued the mission

until 1969.

B-57 assigned to the 8th Bomb Squadron, 35th Tactical Fighter Wing (PQ) at Phan

Rang AB, South Vietnam in March 1969. (USAF Museum)The pilot was responsible for the 250 knot dive run and bomb release, but the

back seat navigator was a second pair of eyes, spotter, observer, navigator and

radio operator. On the pullout, the aircraft and crew were under a four "g"

stress without the use of special equipment. Several crews were lost in midair

collisions, target fixation and ground fire during the night missions. The most

sophisticated piece of equipment in the aircraft was the rheostat which lighted

the manually operated bomb sight. Interdiction Mission (1965) In the early 1960s, the A-26 (B-26 Invader), T-28, and B-57s were the planes

of choice for the interdiction campaigns. Later the F-4, F-105s and AC-130

Spectres became the weapons of choice. According to Thomas Pilsch: Interdiction, "A key part of the U.S. strategy in Southeast Asia was the interdiction of the

supply lines to the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) units in

South Vietnam. These supply routes ran through neighboring Laos and Cambodia and have been

collectively referred to as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In fact, there was no

official "trail." Rather, it consisted of a series of roads and footpaths of

varying condition depending on terrain, weather and level of U.S. interdiction

effort. Where possible, the North Vietnamese used trucks to transport supplies. These trucks became a primary target of the air war over North Vietnam and Laos

(Operations Rolling Thunder, Steel Tiger and Tiger Hound)."

"Some supplies were brought into the western areas of South Vietnam (especially

the A Shau Valley) by truck , but the last part of this supply chain in the

south was conducted by porters using trails cut through the jungle and over the

mountains under difficult conditions. FACs spent a significant amount of effort

looking for signs of movement in these border areas. The further down the Trail

supplies were moved and dispersed, the more difficult it became to locate and

destroy them. Throughout the war, South Vietnam and the United States also used

covert forces to monitor and interdict supply opeations along the Ho Chi Minh

Trail."

The following is from The Role of Airpower in Viet-Nam by Gen John P. McConnell, Chief of Staff, U.S. Air Force, in an address before

the Dallas Council on World Affairs, Dallas, Texas, 16 September 1965. The idea of nuclear umbrella seems antiquated now and the "wishful thinking"

in the speech is self-evident. But in 1965, this message to most people was

reasonable. Strategic Aerospacepower in Viet-Nam?

The question has been raised why we are not using this powerful strategic

capability to force an end to the war in Viet-Nam. There can be no doubt that we could destroy all of North Viet-Nam virtually

overnight. But while this might end the war in Viet-Nam, it could easily spark

a general nuclear war—the very contingency we are determined to avoid and deter. Moreover, such drastic action is neither necessary nor in accord with the declared

intentions and policies of this country.

Our policies in this respect were spelled out by President Johnson in his

historic address at Johns Hopkins University last April when he declared: "We

have no desire to devastate that which the people of North Viet-Nam have built

with toil and sacrifice. We will use our power with restraint and with all the

wisdom that we can command. But we will use it."

And use it we do, but only to the extent necessary to achieve our declared

aims. Toward this end, our strategic capability is utilized in two ways. First, our full nuclear strategic capability must continue to act as a deterrent, that is, provide us freedom of action in

taking whatever military measures are required in Viet-Nam without risking escalation

into nuclear war. Second, our conventional strategic capability is being applied, as the President said, with restraint and discrimination until the rulers of North Viet-Nam become

persuaded to agree to negotiations on an equitable basis. That point will be reached when these rulers recognize that the price of

continued aggression is higher than they are willing and prepared to pay.

It is evident, therefore, that the principle of "strategic persuasion" is not

meant to achieve total military victory, as all-out strategic airpower helped to achieve in World War II. Rather, it

is designed solely as an instrument of foreign policy for the attainment of a

diplomatic objective. The great advantage of such strategic persuasion lies in its flexibility. Under the protection of the nuclear umbrella, its pressure can be increased in measured steps, as may be necessary, while still being kept well below the

level uncontrollable escalation. By the same token, the pressure can be decreased if warranted by a reduction in the intensity of the enemy's aggressive

actions, as Secretary of Defense McNamara indicated in a TV interview a few

weeks ago. Finally, the pressure can be discontinued altogether at any time if it has achieved its purpose or if such action is expected to

foster its achievement.

There are indications that this measured application of the principle of

"strategic persuasion" in Viet-Nam is beginning to take effect. This is not surprising if it is realized that, in the past six months, South

Vietnamese and U.S. aircraft have flown over 15,000 sorties against carefully

selected targets in North Viet-Nam and dropped more than 14,000 tons of bombs

on them.

The targets included primarily lines of communication and military facilities

such as bridges, railroads, highways, barracks, ammunition depots, radar sites

and the like. Most of the targets in North Viet-Nam were attacked for the added

or principal purpose of helping to impede the flow of reinforcements and

supplies to the Viet Cong in South Viet-Nam. And this brings me to the second

new area of aerial operations in that war, namely, the use of airpower against

guerrillas.

Use of Aerospacepower Against Guerrillas

Offhand, it may seem futile to employ airpower in trying to combat extensive

guerrilla activities, especially under conditions as they exist in Viet-Nam.

There are no well defined fronts; virtually all of South Viet-Nam is the

battlefield and combat operations shift rapidly and unpredictably from one

locale to the other. Hiding in the jungle or mixing with the civilian

population, the Viet Cong normally strike in relatively small numbers and

whenever they have the advantage of surprise.

Moreover, the Viet-Cong continue to receive sizable reinforcements and an

incessant flow of materiel from the Hanoi regime. Deputy Secretary of Defense

Cyrus Vance stated in a talk a few months ago that the bulk of the Viet Cong

weapons—at least 60 to 70 percent, including almost all the heavy and modern

weapons—come from external communist sources. But therein lies also one weakness of the Viet Cong which airpower is well suited

to exploit, and that is through what is known as "interdiction" or attacks

against the lines, means and sources of supply.

As you will remember, our initial aerial interdiction effort was limited to

targets in South Viet-Nam in the hope that the conflict could be kept at the

lowest possible level of intensity. But in granting the North Vietnamese a

sanctuary where they could safely collect and store any amount of supplies for

the Viet Cong guerrillas, we found ourselves in the same position as a

narcotics squad that is trying to smash a dope ring by going after the pushers

but has no warrant to enter the ring headquarters from where the pushers are

directed and supplied.

When we began striking targets in North Viet-Nam last February, we not only

added greatly to the effectiveness of our efforts to impede the flow of

supplies to the guerrillas but we also made it increasingly costly for the

North Vietnamese to engage in the provision of these supplies. A bridge and a highway which carry a flow of military supplies to the

guerrillas in the South, normally serve local needs also, and when they are

destroyed as interdiction targets, all other traffic is disrupted at the same

time. This is the direct price which we are now exacting from the North

Vietnamese themselves for their active support of the guerrillas in South

Viet-Nam.

There can be no doubt that aerial interdiction, in combination with naval

surveillance of the sea supply routes, has greatly reduced the support which

the Viet Cong are receiving from the outside and that it will have an

increasing impact on their guerrilla operations throughout the remainder of the

war. But because of geographic conditions, these actions cannot cut off outside

support entirely; they can only reduce it and make it more costly. Nor is

reduction of outside support sufficient, by itself, to defeat the guerrillas

because they will continue to capture weapons and ammunition and to take

whatever else they need from the civilian populace.

Left: Col. Yeager preflighting his B-57 prior to taking off from Bien Hoa Air

Base, South Vietnam, September 1966.

Right: A B-57 from one of Yeager's squadrons flying over Phan Rang Air Base,

South Vietnam. | Col. Chuck Yeager "took command of the 405th Fighter Wing. With his

headquarters at Clark Air Base in the Philippines, Yeager commanded five

squadrons and detachments scattered across Southeast Asia: two tactical bomber

squadrons flying B-57s out of Clark and Phan Rang Air Base in South Vietnam ...

Yeager made an effort to visit and fly with each of these units once every

10-12 days. Flying primarily close air support and interdiction missions in a

B-57, he added 127 flights and 414 hours to his combat record." (Bud Anderson: Yeager Display) |

Canberra.org: Vietnam has a picture of a crew that was one of the first in Vietnam. However, if you

look at the hats closely, you'll see the second man from the right in the rear

row (Ken Blackwell) is wearing the 8th Bomb Squadron Liberty eagle hat.  | (photo courtesy of Ken Blackwell) These men were among the very first to see

action in Vietnam in the Doom Pussy Squadron.

They have been identified as:

Back Row

"Smash" Chandler; (Bear?) "Nails" Nelson; Ed Cook; Jerry Russell; Ken

Blackwell; and Bill Breedlove.

The others are unidentified and believed to be photographers who wanted to "go

on a combat mission". |

8th TBS Assigned to 405th Fighter Wing (1964) In 1964, the 3rd Bombardment Wing was rotated to the States and the 3rd

Bombardment Group was deactivated in 1965 -- after 46 years of continuous

service. However, the 3rd Bombardment Wing changed designators to the 3rd

Tactical Fighter Wing and relocated to England AFB, Louisiana on 8 January

1965. See the 3rd Wing History.) Its three squadrons, the 8th, 13th and 90th Tactical Bomb Squadrons (TBS)

were split.

The 3rd Tactical Fighter Wing kept the 90th Bombardment Squadron, redesignated

as a Tactical Fighter Squadron (TFS) in 1965, and gained the 416th, 510th and

531st TFS. While at England AFB, the 3rd TFW was brought up to full strength

and equipped with the North American F-100 Super Sabre. (Later in 1968 when it

switched to the A-37B it would be reunited with its old sister squadron, the

8th, under the 3rd TFW.)

After this the 8th and 13th Tactical Bomb Squadrons were attached to the 41st

Air Division and later to the 2d Air Division as they mulled over the fate of

the squadrons.

The 8th and 13th TBS were realigned under the Thirteenth Air Force on 24 Apr 1964. At first, the squadrons were scheduled for deactivation --

and in fact, were the last active duty B-57s in the Air Force. However, the

increasing demands for aircraft in Vietnam caused the Air force to reconsider

the deactivation. The aircraft to be moved to Clark AB, Philippines. First

the units went to the 33rd Tac Group (18-28 Jun 65); then to the 2d Air

Division (28 Jun-7 Jul 65); then finally to the 6252nd Tactical Fighter Wing (8

Jul-7 Apr 66) with rotations back to Clark. The Gulf of Tonkin incident was

the impetus to move the Canberras of the 8th and 13th on a rotational basis to

Bien Hoa -- to take on the role of Night Intruder on the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Then both the squadrons were placed under to the 405th Fighter Wing (24 Apr 1964 - Apr 1966) but attached to a number of units over the next four

years. In 1966, the 35th TFW moved to Phan Rang and took over the units until

Jul 68 when the decision was made to deactivate the B-57s. Though the

historical accounts state that the 3rd BG was removed from missions over the

North after their move to Phan Rang in 1966, it appears that the night missions

continued until at least Oct 1967. In 2004, John Hurley wrote, "In the history of the 8th, I found a small discrepancy concerning the

8th's move to Phan Rang AB. It stated that after the 8th moved to Phan Rang, it

did not continue operations in North Vietnam. Actually the 8th did continue

night missions in the North until after October 1967. I do not know when they

were discontinued. I was a pilot in the 8th for two different periods:

1959-1963 and 1966-1967. I'm in the 1000hrs accident free flying picture. No

hat left side."

The 405th's initial deployment to Vietnam was a catastrophe hit. The first two

B-57Bs to land collided with each other on the ground and blocked the runway at

Bien Hoa forcing the rest of the flight to divert to Tan Son Nhut Airport. One

of the B-57Bs dived into the ground during approach at Tan Son Nhut and was

destroyed, killing both crew members. But its woes didn't end there. Mark

Witt stated, in Cat of Doom Story, "November 1, 1964: Two days before the U.S. presidential election, Vietcong

mortars shell Bien Hoa Air Base near Saigon. Four Americans are killed, 76

wounded. Five B-57 bombers are destroyed from the ensuing explosions. Fifteen

were damaged. Whether or not the mortars caused the explosions or faulty bomb

fuses, as some have suggested. the result was devastating to the B-57 force.

It led to the relocation of the force to other bases and finally the

installation of revetments at Phan Rang." (SITE NOTE: People: Chronology states, "October 30: In a Vietcong attack on the US airbase at Bien Hoa, six B-57 bombers are destroyed and five Americans are killed.")

B-57 (probably a -B model) at Da Nang AB,

South Vietnam taken in December 1965. (USAF Museum)

This incident also convinced General Westmoreland to allow the B-57s to enter

combat on February 19, 1965 -- despite qualms that it would violate the Geneva

Convention. This incident is still used as the model of how a small,

well-trained force can inflict serious damage with a hit-and-run mortar attack.

The Viet Cong, in less than five minutes, wiped out an entire squadron of

aircraft.

In February, 1965, a Vietcong attack on the US military airfield at Pleiku

brought a carrier attack on North Vietnam. The US launched Operation Rolling

Thunder , bombing north of the 17th parallel in an effort to get them to quit

aiding the Vietcong and/or fighting in South Vietnam. The first U.S. Air Force

jet raids were flown against enemy concentrations in South Vietnam. B-57

Canberras and F-100 Super Sabres flew against the Viet Cong near An Khe. The US

would drop more bombs on Indochina than it has dropped in World War II. Johnson

increased the US ground troops. The Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN)

suffered great losses through desertions. By the end of 1965, there were

184,000 US troops there; then 385,000 at the end of 1966; and, finally, the

peak number of 543,400 in 1969.

The following is from Historical Text Archive: Don Mabry: By early 1966, Senator J. William Fulbright (Democrat from Arkansas) began to

hold hearings on the war. As they progressed and Fulbright found more of the

truth of the matter, he became a vocal critic of the war and delivered a major

address about "The Arrogance of Power.". Johnson realized that the US needed to

negotiate an end and, by 1968, negotiations had begun with Averill Harriman

leading the US effort. Johnson announced in early, 1968 that he would not seek

re-election so that he would not be an obstacle to the peace talks.

In November, 1968, North Vietnam had responded to the start of negotiations in

Paris by withdrawing 22 of 25 regiments from the northern 2 provinces of South

Vietnam. President Johnson kept up the bombing pressure, and the withdrawals

ceased. Thieu of South Vietnam stalled at sending delegates; he was afraid the

South would lose. When his delegates finally arrived, they stalled for five

more weeks by arguing over the shape of the table.

Richard Nixon, Republican, who narrowly beat Johnson's vice-president Hubert

Humphrey, and US policy changed. In Guam in July 1969, the US said that it

would not try to solve all the problems of all world. This presumed retreat

from overseas activity reflected the national mood for US citizens were tired

of the Vietnam War and feared that the country was trying to do too much. By

1971, however, Nixon was warning of the danger" of "under involvement" and

emphasized that the Nixon Doctrine did not mean the precipitate shrinking of

the US role in the world. The Nixon doctrine seemed to apply primarily to Asia.

Nixon had campaigned that he had a "secret plan" to end the war. Wits said that

he should reveal the secret immediately so as to save lives but, of course, he

waited until he took office in 1969. It turned out that he was going to reduce

US casualties by having the South Vietnamese assume the responsibility of

fighting their own civil war. Nixon proposed to "wind down" the war through

this Vietnamization. US ground troops declined from a high of 543,400 (April

1969) to a low of 60,000 (September, 1972). This move resulted in lower US

casualties and fewer draftees in Vietnam; thus sharply diminishing the domestic

political impact. According to Smithsonian NSAM: While the B-57 possessed superb performance at the time of its introduction, it

had several traits that made the aircraft difficult, and at times dangerous, to

fly. Unlike other early jets, it did not need ground-starting equipment because

a starter cartridge charge, utilizing a powerful propellant, turned a small

turbine that, in turn, brought the compressor rpm of the engines up to a

sufficient level to sustain ignition. This feature, intended to aid in

dispersal to forward airfields produced a heavy, toxic smoke and was

cumbersome. The B-57 did not have control boost to assist the pilot during

maneuvering, which was unusual for an aircraft of its size and speed range.

Combined with limited rudder authority, this omission made loss of control

likely, should one engine fail during a critical phase of flight.

B-57Bs flew more than 31,000 operational sorties in Vietnam and Laos between

February 1965 and October 1969. RB-57s also participated in thousands of

reconnaissance missions during the conflict. The B-57 was not the only Canberra

in Vietnam - the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) also operated the type.

Although it was hardly the most numerous USAF combat aircraft in Vietnam, the

Canberra nevertheless proved itself on missions that were usually much

different from the high-altitude level bombing missions originally envisioned

for the aircraft. As the Vietnam War widened in scope, from lower-intensity

counter-insurgency operations to aggressive air campaigns against an enemy with

the latest Soviet weaponry, the USAF committed larger numbers of front-line

aircraft, previously reserved for their deterrence value against the communist

bloc. Supersonic strike aircraft such as the F-4 and F-105, better suited to

low-altitude weapons delivery, replaced the increasingly obsolescent Canberras,

as did B-52s, which could carry a bomb load more than eight times that of the

2,722 kg (6,000 lb) carried by the B-57. Assistance to RVNAF B-57 Program (1964-1965) "Vietnamization" was the latest catchword in 1964 and its intent was to

turning over more of the fighting to the Vietnamese. According to Joe Baugher: RVNAF B-57, "In 1964, the United States secretly agreed to supply a few B-57Bs to the

Vietnamese Air Force. The United States had initially been reluctant to equip

the Vietnamese Air Force with jet aircraft, since this would be a technical

violation of the Geneva Accords and might further escalate the war. However,

the US bowed to pressure from Saigon. The first VNAF B-57 crews began training

in secret at Clark AFB in the Philippines later in 1964. Later training took

place at Tan Son Nhut instead of Clark. One of the students was none other than

Nguyen Cao Ky, the commander of the VNAF and later president of the Republic of

Vietnam. On August 1, 1965, the blanket of secrecy was removed and an

announcement was made that four B-57 bombers would be provided to the Vietnam

Air Force. Four B-57Bs, painted in VNAF insignia, flew past during a formal

presentation ceremony held on August 9."

The new program began on September 20. Each pilot was to receive 70 hours in

the airplane with no less than 40 training sorties. Navigator training began on

October 11. As the crews completed their training, they went to Da Nang and

flew combat missions with the USAF 8th or 13th Bomb Squadrons, whichever

happened to be on station at the time.

On October 29, 1965, five B-57s from the 8th Bomb Squadron, then based at Da

Nang, were repainted with VNAF insignia and carried out an air strike against a

suspected VC stronghold and landed Tan Son Nhut. After landing, the planes took

off again and joined other VNAF aircraft in a formation flyover of Saigon.

Although manned solely by American crews, this attack was heralded as the

introduction of VNAF B-57s into combat.

However, the RVNAF B-57 training program began to run into serious morale

problems. Malingering brought the training to a standstill. Some Vietnamese

crews flatly stated that they could not physically perform the maneuvers

required in the B-57. From this point on there was very little Vietnamese

activity in the B-57 program. On April 20, 1967, the VNAF B-57 operation was

formally terminated.

8th TBS Rotation (1965-1968) The 8th TBS continued to bounce between Clark AB, PI and Vietnam on a monthly

rotational basis under 405th TFW between 1965-1967. In Oct 67, the 8th and 13th were permanently based out of

Phan Rang.

A small tidbit appeared in the "The Phan Rang Weekly" on August 2, 1967. The

bit tells of two pilots of the 8th SOS reaching the 200 mission mark. But the

interesting point is that they were on "two-month rotational combat tours"

meaning that they rotated in from Clark.Last week's temperature showed an extreme maximum of 102 degree and an extreme

minimum of 76 degrees. Precipitation over a five day period was just .13 of an

inch.

****************************************************

THEIR 200TH MISSION

Capt.Charles R. Rasnic, 8th TBS pilot, flew his 200th combat mission in Vietnam

Sunday.

Lt.Col. Nathaniel Gallagher, the 8th TBS Operations Officer, turned the same

trick on Monday.

Both are completing their third two-month rotational combat tour in Vietnam,

averaging a combat mission per day. The 13th TBS remained assigned to Clark between till the 13th TBS was

deactivated in Jan 68. The 13th TBS aircraft were withdrawn to form the B-57G

unit for the re-born 13th TBS. The last of the monthly rotations was in 15 Jan

68.

Because of losses sustained in Vietnam, twelve B-57Es used for target towing

were returned to Martin in 1965 for modification to the bomber role. The target

towing equipment and control system was removed and the standard bomb system

from the B-57B was installed. Once conversion was complete, most aircraft were

assigned (initially) to the 8th Tactical Bombardment Squadron, 405th Tactical

Fighter Wing at Clark Air Base, Philippines.

The deployments to Vietnam started off as three-month rotations, but soon

became a two-month deployment schedule becomes readily apparent when you

combine the assignments of the 8th and the 13th together. (Source: AFHRA: 80th SOSand AFHRA: 13th BS.) - 13TBS -- Bien Hoa AB, South Vietnam, 5 Aug-3 Nov 1964

- 13TBS -- Bien Hoa AB, South Vietnam, 17 Feb-16 May 1965

- 13TBS -- Tan Son Nhut AB, South Vietnam, 16 May-21 Jun 1965

- 8TBS -- Tan Son Nhut AB, South Vietnam, 18-28 Jun 1965

- 8TBS -- Da Nang AB, South Vietnam, 28 Jun-15 Aug 1965

- 13TBS -- Da Nang AB, South Vietnam, 16 Aug- 16 Oct 1965

- 8TBS -- Da Nang AB, South Vietnam, 16 Oct-16 Dec 1965

- 13TBS -- Da Nang AB, South Vietnam, 16 Dec 1965-17 Feb 1966

- 8TBS -- Da Nang AB, South Vietnam, 15 Feb-18 Apr 1966

- 13TBS -- Da Nang AB, South Vietnam, 17 Apr- 17 Jun 1966

- 13TBS -- Bien Hoa AB, South Vietnam, 15-22 May 1966

- 8TBS -- Da Nang AB, South Vietnam, 15 Jun-15 Aug 1966.

- 13TBS -- Da Nang AB, South Vietnam, 14 Aug-9 Oct 1966

- 13TBS -- Phan Rang AB, South Vietnam, 10- 13 Oct 1966

- 8TBS -- Phan Rang AB, South Vietnam, 12 Oct–12 Dec 1966

(12 Dec 1966 -11 Feb 1967 Missing in AFHRA Record: Assume 13th TBS monthly rotation)

- 8TBS -- Phan Rang AB, South Vietnam, 11 Feb–12 Apr 1967

- 13TBS -- Phan Rang AB, South Vietnam, 12 Dec 1966-11 Feb 1967

(11 Feb - 11 Apr 1967 Missing in AFHRA Record: Assume 8th TBS monthly rotation)

- 13TBS -- Phan Rang AB, South Vietnam, 11 Apr-8 Jun 1967

- 8TBS -- Phan Rang AB, South Vietnam, 7 Jun–2 Aug 1967

- 13TBS -- Phan Rang AB, South Vietnam, 1 Aug- 26 Sep 1967

- 8TBS -- Phan Rang AB, South Vietnam, 26 Sep–22 Nov 1967

- 13TBS -- Phan Rang AB, South Vietnam, 21 Nov 1967-15 Jan 1968. (NOTE: 13th TBS

deactivated 15 Jan

1968. 8th TBS assigned to 35th TFW 17 Jan 68.)

- 8TBS -- Phan Rang AB, South Vietnam, 17 Jan 1968 (NOTE: Combat losses. 8th TBS

down to 8 a/c decision to retire the B-57B in July 1969. )

Casualties (1964-1968): Flying the B-57 was a risky business. Out of the 94 B-57s that were assigned

to the Southeast Asia theatre, 51 were lost in combat (including 15 destroyed

on the ground). By Jul 69 only 8 aircraft were left in the 8th TBS.

Immediately upon deployment of the B-57s to Vietnam did tragedy strike. The

initial deployment (5 Aug-3 Nov 1964) to Vietnam got off on the wrong foot.

Twenty (20) B-57Bs of the 8th and 13th Tactical Bomb Squadrons were deployed to

the Bien Hoa air base near Saigon, marking the first deployment of jet combat

aircraft to Vietnam. The first two B-57Bs to land collided with each other on

the ground and blocked the runway at Bien Hoa, forcing the rest of the flight

to divert to Tan Son Nhut Airport on the other side of Saigon. Joe Baugher site: B-57B, One of the B-57Bs dived into the ground during approach at Tan Son Nhut and

was destroyed, killing both crew members from the 13th TBS, 405th TFW. This

supposedly was the FIRST pilot death in Vietnam.

However, Clarion Ledger differs on the cause of deaths of Capt. Fred "Potlick" Clay Cutrer (pilot) and

1Lt. Leonard L. Kaster (nav). According to the article they were lost to

gunfire in Long Khan Province on Aug. 5, 1964. The remains of Capt. Fred

"Potlick" Clay Cutrer lay buried one meter beneath the surface of a jungle bog

for 33 years, mired in obscurity and hidden from his family's grasp for

closure. In the spring of 1997, the Department of Defense, with the aid of a

Vietnamese native who saw Cutrer's B-57 Bomber plummet to earth in Dong Nai

Province Aug. 5, 1964, made a discovery and started the Cutrer family's healing.

The Virtual Wall stated: "On 6 August 1964, Captain Fred C. Cutrer, pilot, and 1LT Leonard L. Kaster ,

navigator, were returning from a mission in B-57B tail number 53-3870 when

their aircraft crashed into the Song Dong Nai River in Long Khan Province, SVN,

about 25 miles northeast of Bien Hoa. It was and remains unclear whether they

were bought down by enemy fire or if it was an operational loss. In any case,

the remains of the two men could not be recovered. When Captain Cutrer's

memorial was was first published on 06 Oct 2001, neither Cutrer's nor Kaster's

remains had been identified. However, the crash site actually had been located

and excavated in 1997. On 25 October 2001, the government announced

confirmation that Captain Cutrer and 1LT Kaster both died in the crash. Reports

indicate that both ejection seats (and hence both crewmen) were in the aircraft

when it crashed.

In an e-mail dated Wednesday, 22 May 2002, Captain Cutrer's son advised that

while his father's dogtag had been recovered from the wreckage the very small

sizes of the human bone fragments recovered precluded positive identification

of either man.

The recovered remains were buried together in Arlington National Cemetery on 06

June 2002. The privately operated Arlington Cemetery site has a report on the

burial . Press reports reproduced on that site indicate that 1st Lt Kaster (and

presumably Captain Cutrer) was awarded a posthumous Purple Heart at the burial

ceremony. During the next few weeks, more B-57Bs were moved from Clark AFB to Bien Hoa to

make good these losses. Initially, the B-57Bs were restricted to unarmed

reconnaissance missions, but actual combat was not delayed very long.

On November 1, 1964, Viet Cong squads shelled the airfield at Bien Hoa with

mortars, destroying five of the B-57s parked there and damaging 15 others. On

19 Feb 1965, the B-57Bs were released for armed combat operations with the

first mission taking place the same day. The B-57Bs hit North Vietnamese

territory for the first time on March 2, some 25 miles north of the DMZ.

On the second deployment (17 Feb-16 May 1965) to Bien Hoa AB, South Vietnam,

the 13th TBS, 405th TFW lost another crew. According to Scope Sys: POW Bio;Virtual Wall and Far away-So Close: On April 7, 1965, Capt. Arthur D. Baker (nav) and Captain James W. Lewis

(pilot) launched in a B-57B, one in a flight of four aircraft on an

interdiction mission from Bien Hoa Air Base, South Vietnam and targeted in

Xieng Khouang Province, Laos. Their aircraft was last seen descending through

thin overcast toward the target area and it never reappeared. Extensive search

and rescue efforts through April 12th failed to locate either the aircraft or

its crew. On April 14, 1965, the New China News Agency reported the shoot down

of a B-57 approximately three miles north-northeast of the town of Khang Khay.

This was described as the first B-57 shoot down of an aircraft launched from

South Vietnam.

Both crewmen were initially reported missing in action in South Vietnam while

on a classified mission. Their loss location was later changed to Laos. In

January 1974 Major Baker's next-of-kin requested his case review go forward and

he was declared killed in action, body not recovered, in January 1974. Lewis

was declared dead/body not recovered, in April 1982. At the end of the second deployment to Bien Hoa, another tragedy hit. On May

16, 1965, while waiting to take off on a mission, a B-57B exploded on the

ground at Bien Hoa, setting off a whole chain of secondary explosions. The

resulting conflagration destroyed ten B-57s, eleven VNAF A-1H Skyraiders, and a

US Navy F-8 Crusader and caused numerous casualties among air and ground

crewmen.

Grace K. Baldonado wrote on Virtual Wall, "My husband Secundino (Dean) Baldonado was killed in Bien Hoa Air Base,

Republic of Viet Nam. He was killed as a result of a series of explosions of

B-57's. The B-57's were preparing for combat missions. Some of them had already

taken off and others were preparing to be launched when one of them blew up

which caused a chain reaction. It was my understanding that my husband had been

pulling men out and the last time he went in to get someone he was caught in an

explosion."

Damage after Explosion at Bien Hoa (16 May 1965)On the fifth deployment (28 Jun-15 Aug 1965) to Da Nang AB, South Vietnam an

8th TBS crew was lost. According to Virtual Wall, On the night of 21/22 June 1965, Captains Charles K. Lovelace , pilot, and

William E. Cordero, navigator, launched from Tan Son Nhut Air Base in B-57B

tail number 53-3910 for a night flare mission (i.e., a pathfinder mission for

other strike aircraft) over North Vietnam's southernmost province in the

vicinity of the Lao/NVN border. The B-57B went down and both crewmen were lost.

Later in the war their remains were recovered and laid to rest in Section 46 of

Arlington National Cemetery, adjacent to the Memorial Amphitheater.

On the tenth deployment (17 Apr- 17 Jun 1966) to Da Nang AB, South Vietnam, a

13th TBS crew was lost. Task Force Omega noted: The B57 Canberra was a light tactical bomber that first arrived in Southeast

Asia in 1964. As a veteran of operations Rolling Thunder in North Vietnam and

Steel Tiger in Laos, it played an important roll in interdicting communist

supplies moving along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Some of the B57's from the 13th

Bomb Squadron located at DaNang and the 8th Tactical Bomb Squadron at Phan

Rang, South Vietnam had also been equipped with infrared sensors for night

strike operations in Tropic Moon II and III in the spring of 1967.

The Mu Gia Pass was one of two major ports of entry into Laos used by the

communists. When North Vietnam began to increase its military strength in South

Vietnam, NVA and Viet Cong troops again intruded on neutral Laos for sanctuary,

as the Viet Minh had done during the war with the French some years before.

This border road was used by the Communists to transport weapons, supplies and

troops from North Vietnam into South Vietnam, and was frequently no more than a

path cut through the jungle covered mountains. US forces used all assets

available to them to stop this flow of men and supplies from moving south into

the war zone.

On 13 June 1966 Lt. Col. Charles W. Burkart, Jr., pilot; and then 1st Lt.

Everett O. Kerr, navigator; comprised the crew of a B-57 Canberra in a flight

of 3 aircraft conducting a night strike mission against Route 911, the primary

road running through the Mu Gia Pass and south in Khammouan Province, Laos. The

mission identifier for this flight was Steel Tiger.

The three strike aircraft departed DaNang approximately 0100 hours. Prior to

reaching the target area, the flight was forced to separate due to bad weather.

Once Lt. Col. Burkhart's B-57 arrived in the target area, it rendezvoused with

the rest of the flight, the Airborne Battlefield Command and Control Center

(ABCCC) responsible for controlling all air operations in this region and the

Forward Air Controller (FAC) responsible for directing their strike mission.

After checking in with the ABCCC, the strike aircraft were handed over to the

FAC who directed them to proceed with their briefed mission.

At 0154 hours, the last known radio contact was established with Lt. Col.

Burkart and 1st Lt. Kerr. The Canberra's crew transmitted that they were

roughly 8 miles southeast of the city of Ban Som Peng at that time. Further,

they did not indicate they were experiencing any difficulty with the aircraft

or the mission.

During the course of the operation, other aircrews tried to establish radio

contact with Lt. Col. Burkart and 1st Lt. Kerr, but were unsuccessful in doing

so. When the ABCCC was also unable to establish radio contact, the pilot

requested an aerial search and rescue (SAR) operation be initiated. In the poor

visibility and darkness, the other aircrews saw no parachutes. They also heard

no emergency radio beepers emanating from the jungle below.

At first light the SAR aircraft searched the sector in and around the area of

last contact. When no trace of the missing aircraft or its crew was found along

Route 911 or in the surrounding jungle covered mountains, the SAR effort was

suspended. Because of the intense enemy presence throughout the entire region,

no ground search was possible. At the time the formal search was terminated,

both Charles Burkart and Everett Kerr were listed Missing In Action.

At the time of last contact, the Canberra was operating just to the west of

Route 911 as it ran through a densely forested long and very narrow valley with

steep, rugged mountains rising up on both sides. The Xe Rangfai River weaved

its way through the rugged mountains less than ¼ mile east of Route 911 at the

location of loss. The entire sector was heavily defended and densely populated

with communist forces.

The location was approximately 3 miles west of a Binh Tram, a way station used

by communist forces as they moved along the Ho Chi Minh Trail; 8 miles

northwest of Ban Thapachon, 13 miles south-southeast of Ban Senphon; 20 miles

southwest of the Lao/North Vietnamese border and 24 miles south of the Mu Gia

Pass. It was also 58 miles west-southwest of the major North Vietnamese port

city of Dong Hoi.) On the 8th deployment (16 Dec 1965-17 Feb 1966), to Danang, South Vietnam, the

13th TBS, 405th TFW lost a crew. According to Virtual WallBy early 1996 the 8th and 13th Bomb Squadrons from the 405th Fighter Wing at

Clark Air Base, Philippines, were solidly entrenched in South Vietnam. The 13th

Bomb Squadron was attached to the 6252nd Tactical Fighter Wing at Danang and

was spending much of its time on night missions over the Ho Chi Minh Trail in

Laos.

On 10 Feb 1966, Captains Russell P. Hunter, pilot, and Ernest P. Kiefel,

bombardier-navigator, departed Danang in B-57B tail number 52-1575 for a visual

bombing mission, working with a C-130 flareship. The two aircraft were

prosecuting a target near Ban Vangthon when, after his second bombing pass,

Hunter reported an unspecified problem with his aircraft and that he and Kiefel

were leaving the aircraft. The C-130 observed the B-57's impact with the ground

and SAR forces later located the wreckage, but no trace was found of either

crewman. The two men were classed as Missing in Action.

Eventually the Secretary of the Air Force approved Presumptive Findings of

Death for Lieutenant Colonel Hunter (20 June 1974) and Colonel Ernest Kiefel

(15 Jan 1979). Their remains have not been repatriated. On the 13th deployment (14 Aug-9 Oct 1966) to Da Nang AB, South Vietnam, the

13th TBS, 405th TFW lost another crew. According to USAFA Class History: 1959September 19, 1966: Cpt William S. Davis, III was killed in combat while flying

a B-57 in South Vietnam. We have no other details at this time. No Quarter states that he was from Demarest, New Jersey and born on Nov 17, 1936.

Casualty Date was Sep 19, 1966. It was due to hostile action inQuang Ngai

Province. Body recovered. After the deployments ended on 25 March 1968 at Phan Rang, the 8th TBS, 35th

TFW lost a crew member. According to Virtual WallAccording to John E. Retz, Captain, USAF (Ret), "B-57 aircraft crashed on

landing due to battle damage (had one engine out with a loss of hydraulic

pressure) attempted a missed approach which was not successful.

"I was stationed with Dick Hopper (Capt Richard Whan Hopper) at Plattsburgh

AFB, NY, flying B-47's and also provided assistance in his check out in the

B-57 at Hill AFB, Utah, in the summer of 1967." After the deployments ended on 13 Dec 1968 at Phan Rang, the 8th TBS, 35th TFW

lost a crew. (See Mid-air Collision for another account of this incident.) According to Virtual WallOn 13 December 1968 a C-123K On 13 December 1968 a C-123K PROVIDER of the 606th Special Operations Squadron launched from Nakhon Phanom RTAFB,

Thailand, on a night FAC mission over the Ho Chi Minh Trail area. The

low-and-slow C-123K's mission was to obtain visual or infrared sightings of

traffic along the Trail and to act as a controller for bombers - in this case,

B-57 CANBERRA bombers from the 8th Tactical Bomber Squadron, Phan Rang AB, SVN.

Weather conditions along the Trail were good - clear with a half moon, ground

fog, no wind and no cloud ceiling. At 0300 hours, as a B-57 was executing an

attack against ground targets, the B-57 collided with the upper surface of the

circling C-123K. Both aircraft - and nine aircrewmen - went down.

- Only one - 1st Lt Thomas M. Turner from the C-123 - was rescued. The others

simply disappeared into the Laotian jungles about 30 miles southwest of the Ban

Kari Pass. A ground search was impossible due to total enemy control of the

area, but airborne search-and-rescue operations continued until the formal SAR

effort was terminated on 15 December. At that point, the crewmen and their

status were as follow:

- 606th SOS, C-123K call sign CANDLESTICK 44

- 1st Lt Thomas M. Turner, pilot, rescued;

- 1st Lt Joseph P. Fanning, co-pilot, MIA;

- 1st Lt John S. Albright, II, navigator, MIA;

- 1st Lt Morgan J. Donahue, navigator, MIA;

- Then-SSgt Douglas V. Dailey, flight engineer, MIA;

- TSgt Fred L. Clarke, loadmaster, MIA; and

- SSgt Samuel F. Walker, Jr., loadmaster, MIA.

- 8th Tactical Bomber Squadron, B-57B call sign YELLOWBIRD 72

- Major Thomas W Dugan, pilot, MIA, and

- Major Francis J McGouldrick, bombardier, MIA.

None of the men returned with other POWs in February 1973, nor did any of the

released POWs have knowledge of the CANDLESTICK or YELLOWBIRD crewmen. As time

passed, the Secretary of the Air Force approved Presumptive Findings of Death

for the eight missing crewmen - including Major Thomas W. Dugan (20 July 1978).

The 8th TBS, 35th TFW of Phan Rang lost a crew on a date unspecified. The

status was changed to KIA status on June 28, 1978. According to Virtual WallLt Col Norman Dale Eaton, pilot, and Capt Paul E. Getchell, bombardier, flying

a B-57B (tail number 52-1561), were lost on a night interdiction mission about

10 miles south of the western end of the A Shau Valley in Savannakhet Province,

Laos. Although the aircraft was seen going down in flames, there were no signs

that the crew ejected and no contact was made with them on the ground.

The Secretary of the Air Force approved a Presumptive Finding of Death for Lt

Col Paul Getchell on 21 March 1979. As of 09 Nov 2002 the remains of the two

men have not been repatriated. The Guns of Tchepone (Mar 66)The following is from Canberra.org::The Guns of Tchepone

A story of heroism-

and skill As told by: Larry Mason, and Jere Joyner

Bob Mikesh, and Joe Rup, Jr.

On 15 March 1966, near the infamous Tchepone, Laos] (Map of the area)

"… Capt Larry Mason [of the 8th TBS] was on a strafing run on enemy trucks when

his Canberra was hit by anti-aircraft fire. The damage was so severe that the

aircraft rolled almost inverted but held together. After regaining control of

his aircraft, Larry's first thought was that he and his navigator Capt Jere

Joyner, would have to eject. His cockpit indications showed loss of power on

one engine and a fire warning light on the other. Struggling as he reached

forward, Jere passed him a blood-stained message which read, 'Hit badly arm and

leg losing blood."'

Realizing that Jere possibly would not survive bailing out, Larry passed him a

tourniquet and gingerly headed his crippled and radio-less B-57 to DaNang. He

was successful in reaching the base, but the landing gear indicators showed the

left main and nose gear in the intermediate position and the right main gear

down. Unknown to Larry was that one of the shell hits caused all three gear to

drop down and lock, while the cockpit indication was erroneous. Pressed with

getting his navigator to medical aid, yet unable to get a safe gear down

indication, Larry placed the gear handle in the up position on this third pass

at the field and made what he thought would be a gear-up landing. To his

amazement, the aircraft landed smoothly on the extended gear and made a normal

rollout. For this heroic outcome that saved the life of his navigator, Capt

Mason received the Thirteenth Air Force "Well Done" Award, the USAF "Well Done"

Award, the Koren Kolligian Jr. Trophy for 1966, the Order of the Able Aeronaut,

and more important - the Air Force Cross, the only AFC connected with B-57

operations.

A postscript to this harrowing story is that the Canberra, tail number 906 also

survived this encounter, thanks to the crew, and the ground maintenance

personnel that healed its wounds. After nearly three more years of combat, it

was modified as a B-7G and was again returned to combat.

From Robert Mikesh's description in Martin B-57 Canberra, the Complete Record, Robert C. Mikesh, Schiffer Military/Aviation History, 1995

From Colonel Joe Rup, Jr.

"When Larry got back he was make the first and only (that I know of)

single-engine go-around since he had no wing to speak of on the good engine

side and a full wing but no power on the other. Quite a feat!"

| Top L: Right wing of B-57B 53-5906 from the cockpit.; Top R: Right side from

rear of aircraft; Bottom L: From left rear of rear cockpit.

The navigator's instrument panel

is at left upper portion of the

photo. The reddish stain is blood.; Bottom R: Captain Art Kono in Yellowbird 21

made a pass on the same area and seeing another aircraft that had been

destroyed mistakenly reported on his return that Mason and Joyner had been shot

down. The photo shows his reward for the intrusion against the guns. (Photos

Joe Rup, Jr.) |

Pilot Larry Mason adds this:

"From my letter to my wife, Nancy, dated 19 March 1966:

"'Target intelligence has confirmed that there were 16 mm, 37 mm and 57 mm

anti-aircraft gun batteries and six 12.7 mm anti-aircraft gun batteries in the

flack trap that got us. The truck on the road was used as bait to lure us into

that trap. They had us point blank, but we got away. That same day, after we

got hit, there was an all-out effort to knock out those guns. But, it cost.

They shot down one Army Mohawk, one A1E and damaged another, plus my FAC (and

Art Kono's damage). It cost four lives. But, with God's help, I'm still here .

. . '"

And from Jere's letter, written 19 May 1966 to Larry Mason:

"Yes, I did see the ground fire. Just as we made our turn I saw the target

clearly and we had well over 300 KIAS (knots indicated airspeed) and [were]

2000' AGL (above ground level).

Of course, that would have been a good time for about 600 knots. Well, I was a

little puzzled at seeing the target, but now I'm sure it was a mobile radar

van. I looked at the altimeter and saw a flash -- much like a couple of 50 cal.

make-- at times. I knew what it was and called to you. When I looked back out I

could see the tracers coming at us. I must have seen 50 or more and each looked

like it would be a direct hit. It's hard to believe we were hit only three

times. I could see them popping on the right wing, then one came through the

fuselage. Guess you know the rest."

Larry continues:

"The only things passed between Jere and I was the bloody note written on the

back of a target photo, 'Hit badly arm leg losing blood,' and the tourniquet

that I handed back. That, and his looks of encouragement -- and the 'thumbs

up.' Jere, a tall man, was in very good shape -- lifted weights and worked out.

That fact, helped him survive that day."

"Fuel leaks caused the loss of Bud Chambers and crew. Seems that with a fuel

leak, the lowering of gear -- or flaps in the case of Chambers -- caused

streaming fuel to be sucked into the engine. I had determined that, if I ever

took battle damage, I would activate MINIMUM systems to get the airplane on the

ground. Our right flap actuator was no longer connected. The left flap actuator

was connected. On the last final approach, I started to deploy the flaps -- but

stopped. If I had done so, the left flap might have deployed -- the right flap

would not. It would not have been a good time for a roll!"

B-57s at Phan Rang (Mar 66) (Joseph Dias) B-57s at Phan Rang (Mar 66) (Joseph Dias)Friendly Fire Incident (Aug 66) During one of these strike missions on 11 Aug 66, a "friendly fire" incident

occurred. Point Welcome relates an "friendly fire" incident where a 8th TBS aircraft, Yellow bird 18,

made the first run on a US Coast Guard cutter, Point Welcome (WPB 82329).

After the intial run, an F-4 from the 35th TFW finished the job and sank the

cutter. This is also covered at USNI: Naval History with photos of the friendly-fire incident. "Friendly Fire, isn't" has become an old saw and one used to disguise a

multitude of human failings. Now called incidents, they were, and are, the

direct result of the growth of weapons technology and human inability or

willingness to control them. All martial conflicts are evolutionary processes

where coordination and cooperation evolve from the result of disaster. The

August 11, 1966, "Friendly Fire" expended on the United States Coast Guard

Cutter Point Welcome (WPB 82329) was one evolutionary link that forced a small

measure operational union during the Vietnam War.

About 0330, with sunrise just two hours away, the Point Welcome lay to in

Market Time Patrol Area 1A1 three-quarters of a mile south of the 17th

parallel.(2) The officer of the deck., Ltjg. Ross Bell, USCG, and helmsman, GM2

Mark D. McKenney, watched aircraft illuminate contacts outside the Cua

Tung(mouth of Ben Hai River). BM1 Billy R. Russell observed these same contacts

on radar above the 17th Parallel during the previous watch. The morning was

clear and although nothing appeared unusual Bell decided to start both Cummins

V12 engines and move farther south. Moving at a slow five knots, he resumed

patrolling 1A1's thirteen miles of coastline; however, within minutes aircraft

began illuminating the Point Welcome.(3) Bell sent McKenney to awaken Ltjg

David C. Brostrom, USCG, the commanding officer, but before Brostrom arose the

first firing run hit the cutter seriously wounding Bell. In later testimony

Bell said he saw no identification signals from the aircraft, "The next thing

we knew there was illumination directly overhead and a firing run was made."

Bell attempted to turn on the WPB's navigation lights and retrieve the Very's

Pistol but a second firing run "wiped out the bridge completely."

Yellow Bird 18, a B-57 from the 8th Bombardment Squadron made these attacks

following a Sky Spot mission where it dropped its bombs, presumably, on the Cua

Tung. Target. Traget designation came from Blind Bat 02, a C-130 from the U. S.

Air Force 21st Troop Carrier Squadron, from whom Yellow Bird 18 asked earlier

if it had any gun targets. Blind Bat reported negatively until alerted by Spud

13, an OV-1 Mohawk, with Side Looking Radar (SLAR) from the U. S. Army's 131st

Aviation Company. Spud 13, and its relief Spud 14, notified Blind Bat of a

large target that ran south at increased speed from the 17th Parallel. Both

Mohawks had "painted" three to five targets at the Cua Tung River and possibly

mistook the Point Welcome as one of the group. Spud 14 later testified that it was technically, but not practically possible,

that while making turns he could have lost the target and picked another.

However, interpretation of the "paint" either in the air or on the ground was

not a definite science and errors were common. After Spud 13 reported, Blind

Bat illuminated the WPB. At 0340 Yellow Bird 18 made the first "tail attack" at 0340 firing 800 rounds

of 20mm ammunition that "left him [the boat] burning." Following Yellow Bird's second attack the WPB's engines were opened to maximum

speed of eighteen knots that Blind Bat's pilot later estimated to be 30-35

knots.

Bell made one transmission to the Coastal Surveillance Center(CSC) at Da Nang,

"Article[call sign], this is Article India, I am under fire from Vietnamese

aircraft." CSC cooly replied, "Article India, this Article, roger, out." He

then pushed the engine controls to maximum speed. At 0350, in the adjacent

patrol area (1C) the Point Caution, offered help and received "This is India,

affirmative. I have taken hits and request assistance" but even at maximum

speed did not sight the Point Welcome until 0435...

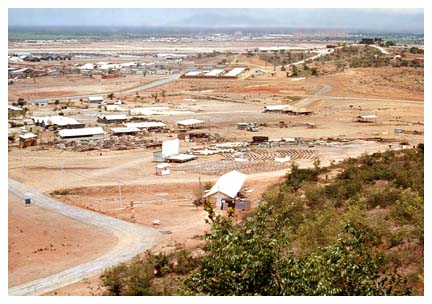

Phan Rang Looking North (1969) (71st SOS)

Phan Rang Looking North (1969) (71st SOS)

Phan Rang Looking West (1969) (71st SOS)

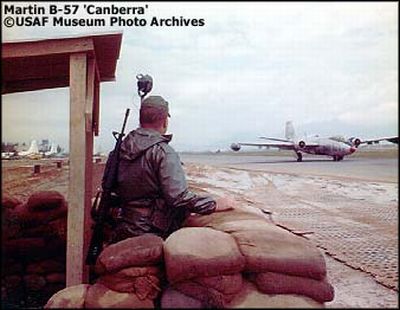

Move to Phan Rang (1966-1969) After the tragic start of their deployments at Bien Hoa (Aug 64-Nov 65), the

unit moved to Tan Son Nhut (May-Jun 65), then it moved to Danang (Jul 65-Oct

66).

In October 1966, 35th TFW wing transferred to Phan Rang Air Base, Republic of

Vietnam, to replace the 366th Wing. With the transfer, the 35th became the

parent wing at Phan Rang Air Base and began flying F-100 aircraft with

Detachment 1 of the 612th Tactical Fighter Squadron. The 8th and 13th Tactical

Bomb Squadrons followed the 35th to Phan Rang Air Base, while the wing gained

an attached organization: the Royal Australian Air Force Squadron No. 2 and its

MK-20 Canberra bombers.

Starting in October 1966, the 8th TBS and 13th TBS were attached to the 35th Tactical Fighter Wing of Phan Rang. From Oct 66 till the 8th left Phan Rang in Oct 69, it remained

in Phan Rang. In July 1969, the B-57s were phased out of the USAF inventory

and the remaining B-57s sent to the boneyard. The 8th was transferred without

equipment and personnel to the 3rd TFW in preparation for its transition to the

A-37B in Jul 69.

The 13th TBS was inactivated in Jul 69 and its assets sent to be modified into

B-52G aircraft. Eleven (11) were withdrawn early to support the B-57G program.

When the aircraft modifications were complete, the 13th TBS moved to Ubon

RTAFB, Thailand with the 8th TFW.

After the 13th departed from Clark, the 8th TBS was deployed to Phan Rang

permanently starting on 17 Jan 68. During this time, the B-57Bs were suffering

combat losses that could not be made up by drawing from ANG/Reserve assets. By

July 1969, the 8th TBS was down to 8 serviceable airframes. The decision to

retire the B-57 came in July 1969.

On October 15, 1969, a B-57B (s/n 52-1551), the last U.S. jet bomber based in

Vietnam, departed from Phan Rang as the United States sought to draw down its

forces stationed within the country before beginning the process of

disengagement from the war. Smithsonian NSAM stated that the National Air and Space Museum selected 52-1551 for its

collection because of that distinction. This aircraft had served with the 8th

Bomb Squadron for more than two years, flying both day and night bombing

missions.

Supposedly the B-57s used their bomb bays to carry more than bombs -- and were

used to bring in goods that couldn't be found in Vietnam. (NOTE: This was a

standard practice during the Vietnam War years as C-141s came home from Vietnam

stuffed with ceramic elephants in the crew bunk area; B-52s heading back to

Fairchild had all sorts of items strapped down in the 47-section near the

liferaft; KC-135s from Utapao headed home filled with teak furniture or rattan

papasan chairs.) The following photos and commentary are from Gene Bonham's website while he was stationed at Phan Rang in 1967

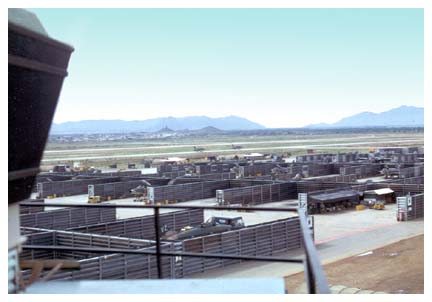

(Gene Bonham)| This was taken from the top of the control tower, looking south east. Many of

the F-100s belonged to the 614th and 615th Tac Fighter squadrons. At the

extreme right were the B-57s of the 8th and 13th Bomber Squadrons.

(I think that you can see the Temple in the background). |

(Gene Bonham)| We spent many a night here at the drive-in. One of the odd things about

it was at times the old TV series "Combat" was playing. So you could

either watch "Combat" or the Gunships (AC-47s) make their nightly runs

around the main gate.....make believe or the real thing. While going to

the theater we also discovered that one could fit the better part of a case

of beer in all the pockets of a set of jungle fatigues. Youth, go figure. |

(Gene Bonham)| Getting ready to load the 20mm cannons on a B-57. The 20mm round has a High

explosive projectile, that's why the little trailer has a "Class A explosive"

sign on it. Every Fighter or Bomber that flew had a full load of 20mm rounds on

board, |

(Gene Bonham)| A couple shots of the "Nose Art " found on the B-57 bombers. There were not

many with art. I think it was up to the individual squadron Commanders. The

Bombers at PRAB were from the 8th or 13th Bomber Squadrons. They would rotate

every few months from Clark AB in the Philippines. When they rotated they would

come in with the bomb-bays loaded with all kinds of goodies (e.g., beer,

cigarettes, candy, Hondas motorcycles,...). Anything these guys could

peddle...and they did. At one time they set up a concession stand at the

theater. |

| A Martin B-57B Canberra of the 8th Bomb Squadron an a mission over Vietnam In

December, 1967, heads for its target. The B-57 was one of the most effective

airplanes against ground targets because of its load carrying ability, loiter

time over the target, and ability to penetrate a given target due to its fast

pull-up capability. Higher performance lighter bombers lacked these qualities.

Dome atop rear fuselage is duplicate of one on lower fuselage. Both contain

TACAN antenna. (Air Power online: G2) |

| Painting: Keith Woodstock: Vietnam 1967, and a B-57 sets out on a night

intruder mission against the Vietcong. This painting appears in the

commemorative book describing the history of the USAF, "From Sabre to Stealth".

(Keith Woodstock: Gallery) |

FAC Interface with B-57 on Night Interdiction in Laos (Nov 1967) The following is excerpted from Magic Gallery: B-57 on the Jimmie Butler Website dealing with the B-57B from the FAC (Forward Air Controller) perspective in

their Cessna O-2 Birddogs. In his references to the B-57s are for "Red Bird"

(13th TBS) and "Yellow Bird" (8th TBS). (See Jimmie Butler: Books for information on books written by Jimmie Butler on the Air War over Laos.) I never worked any B-57s during the day. I worked them as Red Birds or Yellow

Birds coming up from Phan Rang on the nights of 17 November and 23 November

1967. I liked adding a B-57, when available, to our night hunter-killer team,

which normally consisted of my O-2 and a T-28 from the Zorros of the 56th Air

Commando Wing at NKP. Sometimes as we searched a segment of the Trail, Alley

Cat (the night ABCCC controller) would offer us a B-57, and I'd always welcome

them. I guess we rendezvoused using our real TACAN coordinates (since the O-2

really did give the FACs a TACAN) and I suppose we must have turned on our

shielded upper beacon. Otherwise I don't know how the B-57 crew would keep

track of us, although once we flared, the site of the battle was obvious. While

we flew at about 4,200 feet (which was about 3,500 feet above the ground along

the main Route 911 in the lower ground between Mu Gia and Tchepone, the T-28

loitered above us at about 5,000. Seems like the B-57s said they were about

20,000, although that sounds high now that I think of it.

Anyway, all was quiet and pretty dark until my nav (usually Captain Bertram

Bilton) spotted trucks. We would flare and direct the T-28 against the trucks

while the B-57 stayed high above. You can see in the discussion below the more

colorful description (which I wrote in 1980) of what followed.

While we enjoyed the benefits of having a B-57 overhead in the Enforcer role,

the third aircraft increased the dangers of mid-air collisions where the strike

aircraft are flying blacked-out and we generally flew dark as well once the

rendezvous took place with out T-28. The Zorro pilot occasionally asked for a

flash of our beacon if he lost track of our black aircraft flying in the dark.

We used altitude separation as our main defense against mid-airs. Sometimes the

T-28 stayed below out altitude once the strike began, so our main concern

tactic was to tell the Zorro geographically where we were from the target when

he came down through our altitude and climbed back through after the strike.

When I cleared a Red Bird or Yellow Bird for attack from above, we and the

Zorro scrambled off to the side, and I usually dropped a few hundred more feet

when I was well away from the guns. The B-57 usually dropped a funny bomb (as

discussed below) into the mix without any of the three of us ever seeing each

other. A couple of years later—after FACs had been driven higher even at night

when the out-country war had shifted from North Vietnam and Laos to Laos—one of

Jim Roper's friends, Thomas Dutton, was lost in a mid-air collision near

Tchepone between his O-2 and a B-57.

* * * * * * * * * * * Night Strike Aircraft ComparedJust as FAC aircraft differed in their capabilities, there were marked

differences among the aircraft that attacked the trucks and guns at night in

Steel Tiger. One lesson was obvious. Jets that seldom cratered the road in

clear weather in the daytime could not really be expected to hit a truck moving