8th Special Operations Squadron

(1974-Present) |

Acknowledgment: Thanks to John D. Lock, Lt.Col, USA (Ret) and author, for his permission to use his article on Operation Eagle Claw.

Thanks to the Special Operations Warrior Foundation for permission to use their materials about Desert One (Colonel Carney’s article and the AF Magazine articles). Thanks to Tracey White of the Spec War Net for use of the materials dealing with Operation Eagle Claw. Our appreciation for the materials in the Northwest Florida Daily News; USAF Military Fact Sheets; Special Operations.com: 8th SOS; FAS.org; Global Security.org;Skytamer.com; and Crestview Chamber of Commerce webpages. Lastly we are deeply indebted to the historical information found at Air Force Historical Research Agency (AFHRA) on line.  On a Yellow disc within a Blue band, On a Yellow disc within a Blue band,

edged with a narrow White border, a stylized climbing bird,

which is entirely Black.

MOTTO: BLACK BIRDS.

Approved on 19 Jul 1993

8th Special Operations Squadron: By the end of 1975, the entire Air Force SOF capability had been cut to one undermanned wing (the 1st SOW) at Hurlburt Field, Florida, with three squadrons assigned (the 8th, 16th, and 20th SOSs), and two Talon squadrons stationed

overseas (the 1st and 7th SOSs). Barely 3,000 personnel remained in SOF during the late 1970s.

16th Special Operations Wing The following excerpted from 16th SOW. "The 16th Special Operations Wing consists of approximately 7,000 highly trained military professionals who stand ready to conduct special operations missions at a moment's notice. The wing is the largest Air Force unit assigned to the U.S. Special Operations Command, a command responsible for conducting special operations worldwide."

16th SOW

MOTTO: Any time, Any place"The 16 SOW specializes in unconventional warfare. At the direction of the National Command Authorities, the 16 SOW goes into action with specially trained and equipped forces from each service working as a team to support national security objectives. Special operations are often undertaken in enemy-controlled or politically-sensitive areas and can cover a myriad of activities."

"The 16 SOW's motto is, "Any Time, Any Place." The wing stands ready to go worldwide to conduct unconventional warfare, counterinsurgency, or psychological operations. Through special operations, the United States is able to protect its interests in low-intensity conflicts throughout the world."

16th SOW Consolidates with 919th SOW (Reserve) In 1998, the 919th was divided into two associate units at two locations - Duke Field and Eglin AFB. The 5th SOS was grafted into the active duty's 9th Special Operations Squadron at Eglin AFB as an associate unit. This placed all MC-130P Combat Shadow aircraft in the entire Air Force inventory under the control of the active duty's 16th Special Operations Wing.

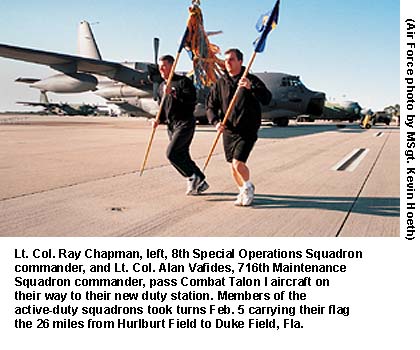

Following that transition, all MC-130E Combat Talon I aircraft were placed in the Air Force Reserve at Duke Field. As a result, the 711th SOS became the only active associate unit in the Air Force. In February 2000, the active duty 8th Special Operations and the 716th Maintenance Squadron moved from Hurlburt Field to Duke Field to share the Combat Talon mission with the 919th SOW. This makes the 919th SOW the only reserve unit in the Air Force with active duty people assigned to it. The 919th SOW received its 10th Outstanding Unit Award as a result of the successful transition to active associate units.

The Wing employs approximately 1300 reservists and 300 federal civil service employees to meet its mission requirements. The following appeared in Oct 2002 issue of the Air Force Reserve Magazine, Citizen Airmen: Oct 2002 Smooth TransitionSpecial operations unit blends forces, sustains readiness

Pamela S. Nault

Callused hands covered with grease and grime that are seemingly permanently embedded beneath fingernails. Skin roughened and irritated through use of harsh industrial-strength cleaners. Knuckles that never seem to heal from repeated blows against engine components while manipulating wrenches in tight places. Such is the life of a turboprop jet engine mechanic. Such is the daily routine of Senior Airman Sean Preston.

"Our hands really take a beating," said the 21-year-old aerospace propulsion apprentice assigned to the 919th Maintenance Squadron, a subordinate unit of the Air Force Reserve's 919th Special Operations Wing at Duke Field, Fla. "It goes with the territory of maintaining the MC-130 (Combat Talon I). It's what we do here, and it's especially important as we fight the war on terrorism."

In Total Force tradition, Preston, a reservist, works shoulder to shoulder with Airman First Class Shaun Gamble, a 19-year-old propulsion mechanic assigned to the 716th MXS, a subordinate unit of the active duty's 16th SOW at Hurlburt Field, Fla.

"It's like we're joining hands, rough hands, to accomplish the mission," Preston said.

Although the partnering of reservists and active-duty members is routine in today's Air Force, the situation surrounding Preston and Gamble's working relationship represents a unique and historic melding of special operations forces.

16th SOW MC-130s in formationAbout 2 1/2 years ago, officials at Headquarters Air Force Special Operations Command, Hurlburt Field, and HQ Air Force Reserve Command, Robins Air Force Base, Ga., decided that consolidating special operations assets into two associate organizations would better integrate the forces, improve operations and save money, all without having a detrimental effect on the mission.

"With limited resources, it just made sense to combine four special operations flying squadrons, and corresponding maintenance squadrons, that operate the same weapons systems," said Col David C. Peel, chief of programs in HQ AFRC's Directorate of Plans and Programs. With 22 years of experience in special operations, Peel was part of the transition team that implemented the consolidation at Duke. "There have been a few growing pains along the way, but overall it's been a smooth transition."

In a traditional associate unit setup, the Reserve's 5th Special Operations Squadron, which belongs to the 919th SOW, joined forces with the active duty's 9th SOS at Eglin AFB, Fla. Crews and maintainers from the two units work in unison to meet mission requirements in MC-130P Combat Shadow aircraft, which are now owned by the 16th SOW. With the move, the 5th SOS transferred ownership of its five aircraft to the active duty.

The Combat Shadow's primary mission is to fly clandestine or low-visibility missions into politically sensitive or hostile territory to provide air refueling for special operations helicopters. The aircraft's secondary mission is to airdrop leaflets, small special operations teams and equipment.

What makes the arrangement between AFSOC and AFRC unique is the second associate unit formed by the two commands. In this arrangement, the Reserve's 919th SOW assumed ownership of the Air Force's inventory of 14 Combat Talon I aircraft and shares flying and maintenance responsibilities with the active duty's 8th SOS and 716th MXS. Approximately 300 active-duty people now report to Duke Field to do their jobs each day.

The Combat Talon I is capable of delivering people and equipment, either from the air or on the ground, deep into hostile territory during day or night, even under adverse weather conditions. In addition, the aircraft has an aerial refueling capability for special operations helicopters.

"It's working well," said Brig. Gen. Mark Stogsdill, 919th SOW commander, referring to the associate unit arrangement. "It's a more efficient way of doing business."

In the aftermath of the attacks on America's homeland Sept. 11, 2001, special operations forces from the various military services have been heavily involved in America's aggressive war on global terrorism.

"We're tested with each mission we conduct in support of Operation Enduring Freedom, and we haven't missed a (scheduled) sortie," Stogsdill said. "Our perfect combat mission effectiveness record with 100 percent maintenance mission efficiency says it all about our flyers and maintainers."

The general said his unit was fortunate to be able to use several previously established Reserve associate programs as a guide for the Combat Shadow consolidation. In addition, he said, getting the first and only active associate unit off the ground and running at its current high level of efficiency demonstrated the great teamwork between the 919th and 16th SOW.

"Working together with the active duty is something we've done for years, and it was just a matter of enhancing those relationships with an innovative idea and stepping into new territory with this blend of forces," said Stogsdill, a master navigator with more than 6,500 flying hours, including 450 combat hours in AC-130 Spectre gunships. "What we did here may serve as a role model for other weapons systems to follow."

"We in the 16th SOW are honored to fight side by side with the men and women of the 919th SOW," said Col. Lyle Koenig, 16th SOW commander. "There's no question we can't do our mission without them, and we look forward to our continued partnership."

Among the expected benefits of the consolidation was cost savings. Active-duty and Reserve officials agree that the relationship is saving money, but defining the savings in specific terms is a challenge, said Bascom R. Grant Jr., 919th SOW financial analysis officer.

"There are so many variables that come into play that it's difficult to give a firm cost-savings number," Grant said. "The benefit of streamlining the weapons systems in one place, coupled with integrated training, is not necessarily measured in dollars. The active associate wing eliminated approximately 30 percent of the active-duty operators and maintainers."

Grant said reducing the work force while maintaining the same number of flying hours produces a substantial savings.

Preston and Gamble, who each have worked on both the Combat Shadow and Combat Talon aircraft, said the consolidation benefits maintenance workers.

"Previously, I'd work on the Shadow one day and the Talon the next," Gamble said. "The consolidation made work easier because of the consistency of working on one aircraft on a regular basis."

In February, President George W. Bush paid a visit to Eglin AFB to honor the "quiet professionals," as special operations people are known. During his visit, Bush thanked the commanders for their leadership, praised the war-fighting capability of special operations forces in Afghanistan, and announced a $48 billion budget proposal to fund the war on terrorism, homeland security and a pay raise for military members.

"Our military has a new mission for the 21st century," the president said. "It came suddenly, but you were ready. You destroyed Afghan terrorist training camps and freed a country from brutal oppression."

Addressing the men and women in uniform, Bush said, "You perform with daring and dedication. You've made an impression on the enemy. You've given the terrorists around the world their first glimpse at their fate."

"We were especially honored when President Bush visited Eglin Air Force Base and specifically commented on our Total Force," Koenig said.

Preston was one of more than 8,000 military people and family members who turned out to welcome the president.

"It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see in person the president of the United States," said Preston, a native of Panama City, Florida. "He made it very clear that the war on terrorism is a priority. His positive comments about the military made me proud to wear the uniform."

Since October 2001, several hundred reservists from the 919th SOW have been serving on active duty in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. Gamble said the 12-hour shifts that are necessary to keep up with the war's demands are challenging, but morale among the people is very high.

"We do what's expected of us and then do even more," said the Gastonia, N.C., native.

Preston, a part-time student, said the increased duty hours forced him to more closely manage his time to keep up with his studies. His goal is to obtain a nursing degree, compliments of the GI Bill, and apply for a commission.

"I'd like to complete my military service as an aeromedical flight nurse," he said. "No more grease and grime."

Meanwhile, the associate unit transition continues to be a work in progress. All of the major work, such as modifications to buildings, new construction, and the movement of aircraft, equipment and personnel, is complete. Now it's a matter of working out the smaller details and fine-tuning the processes, Stogsdill said.

"A team effort made our conversion to two associate units a success, while maintaining our combat capability to effectively conduct the war on terrorism," he said. "That speaks highly of the talented men and women in special operations. I'm proud to serve with them and to be a part of this historic associate unit transition."

(Ms. Nault is chief of the Community Relations/Environmental Division in the AFRC Office of Public Affairs at Robins AFB.)

8th Special Operations Squadron The 8th Fighter Squadron reverted to its old name the 8th Special Operations Squadron on 1 Mar 1974 when it was assigned to Eglin Air Force Auxiliary Field No. 9 (Hurlburt Field) FL. Hurlburt Field is in the Fort Walton Beach area.

It was first assigned to the 1st Special Operations (later, 834th Tactical Composite; 1st Special Operations) Wing on 1 Jul 1974. It was later assigned to the 1st Special Operations (later 16th Operations) Group on 22 Sep 1992.

It transitioned to the MC-130 "Combat Talon I". The squadron absorbed the personnel and equipment (Lockheed MC-130E Combat Talon I) of the inactivated 318th Special Operations Squadron.

On 20 June 1975, the 8th SOS absorbed the assets of the 415th Special Operations Training Squadron gaining the Lockheed AC-130A and AC-130H gunships. Later that year these assets were transferred to the 919th Special Operations Group and the 16th Special Operations Squadrons, respectively.

Talon I flying near Yuma, AZ, early 80s (John Franklin)The first of the MC-130H, Combat Talon IIs, arrived on 17 October 1991 and later that year the squadron was split into two sections (Talon I and Talon II). The lineal descendant of this proud squadron is the famed 8th Special Operations Squadron ("Blackbirds") of Hurlburt Field, Florida flying MC-130E Combat Talon I aircraft as part of the 16th Special Operations Wing. The 8th Special Operations Squadron is currently the second longest continuously operational active duty squadron in the U.S. Air Force since its inception in 1917. The primary mission of the 8th SOS is insertion, extraction and re-supply of un-conventional warfare forces and equipment into hostile or enemy-controlled territory using airland or airdrop procedures. Numerous secondary missions include psychological operations, aerial reconnaissance and helicopter air refueling.

To accomplish these varied missions, the 8th SOS uses the Combat Talon I, a highly specialized variant of the Lockheed C-130. The history of the Talon I stretches back to 1966 when the first C-130E was modified and a small squadron established at Pope Air Force Base, N.C. Later that year four of these specially modified MC-130s were deployed to Nha Trang, Republic of Vietnam, in support of the war in Southeast Asia.

During the Southeast Asia conflict, Combat Talon Is were extensively involved in covert/clandestine operations in Laos and North Vietnam. They routinely flew unarmed, single-ship missions deep into North Vietnam under the cover of darkness to carry out unconventional warfare missions in support of Military Assistance Command's Special Operations Group.  On a Yellow disc within a Blue band, On a Yellow disc within a Blue band,

edged with a narrow White border, a stylized climbing bird,

which is entirely Black.

MOTTO: BLACK BIRDS.

Approved on 19 Jul 1993In early spring 2000, the 8th SOS transfered to Duke Field with its Combat Talon I aircraft. Duke Field (or Eglin Air Force Base Auxiliary Field 3, Florida) is six miles south of Crestview. The unit combined its forces with the 711th SOS, which also flies the Combat Talon I aircraft.

Under the associate unit concept, an active-duty unit owns the aircraft and Reserve crews and maintainers augment the missions. In this case, however, the Air Force Reserve will own all the Combat Talon I aircraft as both units form an associate unit flying the Combat Talon I aircraft.

As of Feb 2000, they have become the Air Force's only active-duty associate unit serving with the Air Force Reserve Command's 919th Special Operations Wing. The move is part of an overall plan for Air Force Special Operations Command to combine Reserve and active-duty components onto common airframes. These changes result from mission changes, adjustments for efficiency, congressional directives and implementation of the expeditionary aerospace force concept.

Their mission includes: supporting unconventional warfare missions and special operations forces. The MC-130 aircrews work closely with Army Special Forces and Navy SEALs (sea-air-land teams). In addition, the 8th is able to conduct psychological warfare operations by air dropping leaflets and can drop the world's largest conventional bomb, the 15,000 pound BLU-82, for special attack or psychological effect. The following is from Special Operations.com: 8th SOS: The primary mission of the 8th SOS is insertion, extraction and re-supply of un-conventional warfare forces and equipment into hostile or enemy-controlled territory using airland or airdrop procedures. Numerous secondary missions include psychological operations, aerial reconnaissance and helicopter air refueling. To accomplish these varied missions, the 8th SOS uses the Combat Talon I, a highly specialized variant of the Lockheed C-130. The history of the Talon I stretches back to 1966 when the first C-130E was modified and a small squadron established at Pope Air Force Base, N.C. Later that year four of these specially modified MC-130s were deployed to Nha Trang, Republic of Vietnam, in support of the war in Southeast Asia. During the Southeast Asia conflict, Combat Talon Is were extensively involved in covert/clandestine operations in Laos and North Vietnam. They routinely flew unarmed, single-ship missions deep into North Vietnam under the cover of darkness to carry out unconventional warfare missions in support of Military Assistance Command's Special Operations Group.

Since its initial development, major modifications have been made to the Combat Talon I to ensure its continued viability through technological superiority. Today's Combat Talon I with its state-of-the-art computer systems is capable of terrain following operations as low as 250 feet in all weather conditions. Crews from the 8th SOS can drop equipment or personnel on small, unmarked drop zones with pinpoint accuracy, day or night. Additionally, the Talon I gives the squadron a truly global reach with the ability to receive gas from Air Force tanker aircraft and transfer gas to special operations helicopters. The Talon I is equipped with an electronic warfare package to counter the threat of detection by enemy radar by deceiving or jamming many types of enemy radar. The aircraft also employs infrared jamming pods, chaff, and flares to combat the threat of enemy missiles. These updates ensure the Combat Talon I will remain a weapon of choice into the 21st Century. Combat Talon I forces have been tasked on numerous occasions to use their unique capabilities in the interest of national objectives. In 1970, Combat Talon Is led assault forces on the North Vietnamese Son Tay prisoner of war camp. During the raid they also functioned as an airborne jammer and command post, providing vectoring information for mission aircraft.

| NELLIS AIR FORCE BASE, Nev. (AFIE) -- Staff Sgts. Clay Johns and Tommy Mazzone, loadmasters from the 8th Special Operations Squadron at Hurlburt Field, Fla., release a palette during an airdrop mission during Millennium Challenge 2002 on July 29. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Aaron D. Allmon II) (VIRIN: 020729-F-7823A-012) |

| NELLIS AIR FORCE BASE, Nev. (AFIE) -- Tech. Sgt. Tommy Mazzone, a loadmaster from the 8th Special Operations Squadron at Hurlburt Field, Fla., loads a palette aboard a MC-130E Combat Talon on July 29 for an air drop during Millennium Challenge 2002. MCO2 is the premier joint warfighting experiment, bringing together live field forces and computer simulation and runs July 24 to Aug. 15. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Aaron D. Allmon II) (VIRIN: 020729-F-7823A-010) |

| NELLIS AIR FORCE BASE, Nev. (AFIE) -- Staff Sgt. Clay Johns, a loadmaster from the 8th Special Operations Squadron at Hurlburt Field, Fla., peers out of a MC-130E Combat Talon window before an airdrop during Millennium Challenge 2002 on July 29. MC02 combines live field forces and computer simulations at several locations across the United States with the purpose of testing and validating several joint and service-specific experimental warfighting concepts. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Aaron D. Allmon II) (VIRIN: 020729-F-7823A-008) |

Move to Duke Field A relay of unit members carried the guidon of the 8th Special Operations Squadron 26 miles from their old home at Hurlburt Field, Fla., to their new home at Duke Field, Fla., on 5 Feb 2000. The 8th SOS is now the Air Force's only active duty associate unit. The Reserve owns the field's six Combat Talon I aircraft, while the 8th SOS provides aircrews and maintainers who share flying time and upkeep on the airplanes. The following is excerpted from and Special Operations.com:

In early spring 2000, the 8th SOS transfered to Duke Field with its Combat Talon I aircraft. The unit will combine its forces with the 711th SOS, which also flies the Combat Talon I aircraft.

Under the associate unit concept, an active-duty unit owns the aircraft and Reserve crews and maintainers augment the missions. In this case, however, the Air Force Reserve will own all the Combat Talon I aircraft as both units form an associate unit flying the Combat Talon I aircraft.

The move is part of an overall plan for Air Force Special Operations Command to combine Reserve and active-duty components onto common airframes. These changes result from mission changes, adjustments for efficiency, congressional directives and implementation of the expeditionary aerospace force concept. The following is an AFRC News Service from a 919th SOW news release (Release No. 00018 - 02/09/00). Squadrons relocate, become active-duty associate unitsDUKE FIELD, Fla. - Cheers from onlookers rang out as members of the 8th Special Operations Squadron trotted onto the flag-lined street of their new home Feb. 5.

After 26 years at Hurlburt Field, Fla., six MC-130E Combat Talon I aircraft along with aircrews and maintainers transferred 26 miles away to Duke Field to serve with Air Force Reserve Command’s 919th Special Operations Wing.

The active force’s 8th SOS departed its Hurlburt home in gala fanfare, with members of the squadron forming a relay to carry the unit guidon from Hurlburt to Duke Field. The move began a new chapter in Air Force history as the squadron became the Air Force’s only active-duty associate unit. A small ceremony after the run signified the birth of the active associate unit. Another active-duty unit, the 716th Maintenance Squadron, “stood up” at Duke Field as part of the active-duty associate unit.

In an active-duty associate unit, the Reserve owns the aircraft and the active force provides aircrews and maintainers who share their mission of flying and maintaining aircraft.

Although the 8th SOS and 716th MXS work at Duke Field on Reserve aircraft, they remain part of the 16th SOW, headquartered at Hurlburt. Approximately 300 active-duty members will be integrated into the flying and maintenance units at Duke with the Reserve wing.

The 919th SOW originally owned eight Combat Talon I’s flown by the 711th SOS. Now all 14 Combat Talon I aircraft are at Duke Field. The move is part of an overall plan for Air Force Special Operations Command to combine Reserve and active-duty components onto common airframes.

Col. David J. Scott, 16th SOW commander, explains that there a bit of sadness with the 8th SOS leaving Hurlburt. "The 8th SOS and the maintainers who keep the MC-130E’s flying have the richest heritage in the wing. We'll feel loss when the Talon I’s depart their Hurlburt Field home. That being said, uniting the Talon community at Duke will join our active-duty force with the veterans now serving with the Reserve. That’s a good thing."

Scott added that a larger, combined force operating from one base will be stronger and more versatile than two smaller ones separated by 26 miles.

"Working together with the active duty is something we’ve done for years, and we look forward to having them here at Duke Field," said Col. Mark Stogsdill, 919th SOW commander. "It’s an innovative idea, and we’re going into new territory with this blend of forces."

The transfer of the Talon I’s to Duke Field is the 919th SOW’s second reorganization in the past six months. The wing’s other flying squadron, the 5th SOS, which flies MC-130P Combat Shadows, formed up with its active-duty counterpart at Eglin AFB, 17 miles south of Duke.

In October, the 919th SOW gave up all five of its Combat Shadow aircraft at Duke and transferred its Combat Shadow squadron and maintenance workers. The squadron became a Reserve associate unit with the active force’s 9th SOS. Under the Reserve associate unit concept, an active-duty unit owns the aircraft and Reserve crews and maintainers augment the missions. There are several Reserve associate units throughout the Air Force, mostly in Air Mobility Command as well as Air Combat Command and Air Education and Training Command.

MC-130P Combat Shadows and MC-130E Combat Talon I aircraft have similar missions, but the Combat Talon I’s have more instruments designed for covert operations. Both aircraft fly infiltration/exfiltration missions - airdrop or land personnel and equipment in hostile territory. They also air refuel special operations helicopters and usually fly missions at night with aircrews using night-vision goggles. The Combat Talon I, however, has an electronic countermeasures suite and terrain-following radar that enables it to fly extremely low, counter enemy radar and penetrate deep into hostile territory.

The 919th SOW is the only Air Force Special Operations Command-gained unit in the Reserve and has some 1,200 reservists assigned. Approximately 300 full-time civilian/reservists are employed at Duke Field.

711th Special Operations Squadron According to Global Security.org, "The 711th SOS has 8 of the Air Force's inventory of 14 MC-130E Combat Talon I aircraft assigned to it. It transitioned to that aircraft from the AC-130A Spectre gunship beginning in September 1995. The mission called on the squadron to perform specialized day or night low-level delivery of troops or cargo into denied or hostile areas."

In early spring 2000, the 8th SOS transferred to Duke Field with its Combat Talon I aircraft and combined its assets with the 711th SOS under the associate unit concept. In this concept, an active-duty unit owns the aircraft and Reserve crews and maintainers augment the missions. However, in this case, the Air Force Reserve will own all the Combat Talon I aircraft as both units form an associate unit flying the Combat Talon I aircraft.

711th SOS Loadmaster on Talon I MC-130E."The move is part of an overall plan for Air Force Special Operations Command to combine Reserve and active-duty components onto common airframes. These changes result from mission changes, adjustments for efficiency, congressional directives and implementation of the expeditionary aerospace force concept."

Duke Field The following is from the Crest View Chamber of Commerce: DUKE FIELD

919th Special Operations Wing

The 919th Special Operations Wing is the only Air Force Reserve unit in Air Force Special Operations Command. In serveral ways, the 919th SOW is unique in the way it is organized. The Wing's two flying units, the 5th Special Operations Squadron, and the 711th Special Operations Squadron, fly two types of aircraft and operate from two locations inthe area. Additionally, units are divided into two different types of associate units.

The 711th SOS is an associate unit and is the only one of its type in the Air Force--called an active associate unit. The difference is that the Air Force Reserve owns the aircraft and the active duty provides the crews and maintenance personnel to share the mission. Recently, the Air Force transferred all 14 Combat Talon I aircraft to the Air Force Reserve with the 919th SOW. The 711th SOS, which flies MC-130E Combat Talon I aircraft, shares its mission of flying and maintaining the aircraft with the active duty's 8th Special Operations Squadron and the 716th Maintenance Squadron. The 919th SOW maintains operational control of the Combat Talon Is;the 8th SOS and 716th MXS report to the 16th Special Operations Wing at Hurlburt Field, Florida.

The 919th SOW's other flying squadron, the 5th SOS, is part of the traditional associate unit where the active duty owns the aircraft and reserve forces augment the mission. The 5th SOS is located at Eglin AFB, Florida, 17 miles south of Duke Field. Together with the 719th Maintenance Det 1, the 5th SOS shares the mission of flying and maintaining MC-130P Combat Shadow aircraft with the active duty's 9th SOS and 16th Maintenance Squadron. Approximately 150 reservists and 45 full-time civil service work in the 5th SOS and Maintenance Detachment 1. The 9th SOS and 16th MXS are part of the 16th Special Operations Wing.

The main part of the 919th SOW is located at Eglin Air Force Base Auxiliary Field 3, Florida (Duke Field) six miles south of Crestview. The 919th SOW employs more than 1,200 reservists and 300 full-time civil service employees. The Combat Talon I aircraft are located at Duke Field. The wing's payroll is more than $28 million annually, and the wing generates an estimated $53 million yearly in the Northwest Florida panhandle.

64-0566 MC-130 Combat Talon I inflight, presently with 711th SOS

(Bart Jingst )

Operations of the 8th SOS:- Operation Eagle Claw: Iranian Hostage Rescue Mission (April 1980): On November 4, 1979 a mob in Iran stormed the US Embassy and took the staff and USMC security contigent hostage. In all, 52 Americans were captured and were being held by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and it was unclear whether they were being tortured or readied for execution. Within hours, the newly certified US Army Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (Airborne) was on full alert and plans were being hastily drawn up for a rescue. Unfortunately, the plans went awry and soon turned into disaster.

The following was excerpted from an article by John D. Lock, former ranger and author, at Operation Eagle Claw. Despite the tragic accident that aborted the mission, the bravery of the men involved in this operation is unquestioned and needs to be retold.

To Fight with Intrepidity: Operation Eagle Claw

Denigrating the U.S. as the "Great Satan," a mob of militant followers of the Ayatollah Khomeini stormed the American Embassy in Tehran on 4 November 1979 and took sixty-six Americans hostage. Finally, it was determined that it was a matter of national honor as well as moral and political obligation to conduct a military operation to rescue the remaining fifty-three captives. The mission went to Colonel Charlie A. Beckwith. A veteran of Korea and Vietnam, "Chargin' Charlie" was a hardened Green Beret and Ranger who was considered to be the premier U.S. expert in unconventional warfare.

Colonel Beckwith was commander of 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (1SFOD-D) more commonly referred to as "Delta Force," a secret...at the time...elite team of commandos who were specifically trained in a number of antiterrorist tasks, one of which was to surreptitiously infiltrate target areas dressed in civilian clothes and free hostages from buildings.

On 11 April 1980, President Carter authorized the rescue mission to be conducted thirteen days later, on the 24th. The mission called for a group of 130 Delta, Rangers, drivers, and translators to be inserted into the Iranian desert by a support force of fifty pilots and air crewmen. Six C-130 Hercules transports were to lift the men, their equipment, and helicopter aviation fuel from the Egyptian air base at Qena to the island airfield of Masirah off the coast of Oman for a refueling stop.

From there, the force would fly to a secret landing strip in Iran, designated "Desert One." Located 265 nautical miles from the hostages held in Tehran, this site would be secured by the Rangers. Eight Sea Stallion RH-53D helicopters launched from the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Nimitz on station in the Arabian Sea would join them.

Refueled at Desert One by C-130s carrying fuel bladders, the helicopters would depart prior to dawn to transport the assault force of 120 men to a remote mountain hideaway designated "Desert Two" located fifty miles from Tehran. After their departure, the remaining Ranger security element and aircraft would sterilize and depart Desert One and return to Qena.

Later that evening, the commandos would clandestinely depart Desert Two and drive in vans and trucks to Tehran to storm the American Embassy compound at around 2300 to free the hostages. Approximately forty minutes after the assault commenced, the helicopters would arrive from their hide site, about fifteen miles from Desert Two, to load the freed hostages and the commando force either in the vicinity of the embassy compound or a nearby soccer stadium.

Two AC-130H Spectre gunships would be on station overhead to interdict any Iranian mobs on the ground and to prevent any Iranian Air Force aircraft from taking off at a nearby airfield.

As the assault was commencing by the Delta team at the embassy compound, eighty Rangers would be airlifted from Qena to an isolated desert airstrip at Manzariyeh. Located thirty-five miles south of Tehran, this airstrip was part of an unoccupied former bombing range and had an asphalt paved runway that would be secured by the Rangers and used by C-141 Starlifters. Withdrawing from the embassy compound to the airstrip by helicopter, the Delta commandos and hostages would load the Starlifters. Then they, along with the helicopter crews, drivers, translators, and DOD agents...select individuals who were operating in Tehran in support of the rescue attempt...would depart for Qena, mission complete.

Once the other elements were lifted out, the Rangers would collapse their perimeter and fly out themselves. Delayed demolition charges would ensure the destruction of the helicopters left behind.

At least, that's how the plan was to work in theory. After a couple of false starts, the mission was launched from the United States on 20 April. On 24 April, the majority of the ground force, to include a detail of Rangers from C Company, 1st Battalion, 75th Rangers, boarded two C-141s and flew to Masirah Island. Later that evening, they departed for Desert One.

At 1930 on the deck of the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Nimitz, eight Sea Stallions crewed by Marines rose in formation and began their fateful six-hundred-mile flight to Desert One under radio listening silence. Maintenance problems caused one helicopter to be abandoned along the way and a second to abort and return to the Nimitz. The mission was now down to the minimum number of helicopters Beckwith thought necessary to accomplish the mission.

At Desert One, Rangers deployed to establish security and a road watch while Delta support personnel prepared to receive the soon to be arriving helicopters. The Ranger road watch team had no sooner off-loaded a jeep and spread out when a large Mercedes bus drove up to the field. Stopping only after shots were fired over the bus, the forty-five distressed Iranians were unloaded from the bus and secured.

Minutes later, another approaching vehicle was spotted, a small fuel truck. Failing to halt, the vehicle was set afire by an antitank rocket fired by a Ranger. Quickly exiting the burning truck, the driver ran a hundred yards back to a pickup that had moved into the perimeter undetected. In a blaze of rubber and tossed sand, the pickup with its two passengers escaped in a hail of bullets.

The last two helicopters arrived at Desert One, nearly an hour and a half late. But, with their arrival, the mission's fate had been sealed, for one of the last two aircraft had sustained a crippling mechanical malfunction. With the mission now down to only five operational helicopters, the mission was aborted.

The task then at hand was to close up Desert One and get everyone safely back to Egypt. At approximately 0200, while maneuvering to top off with fuel from a C-130, a Helo pilot became disoriented in the great swirls of dust created by his engine and that of the C-130. Moving left, then right, the helicopter banked and crashed into the refueling C-130, creating a mammoth fireball in the desert night that caused fuel and debris to rain all about.

From the side troop doors of the stricken C-130, thirty-nine soldiers tumbled or were carried out while other soldiers risked their lives to rescue several unconscious men trapped on the ground near the raging inferno. The five Air Force crewmen in the C-130 cockpit as well as three Marines in the helicopter perished in the intense flames. Four Army soldiers suffered serious burns.

All helicopters were immediately abandoned and for the entire force of Delta, Rangers, and support personnel to load on the remaining C-130s. Equipment was jettisoned from the C-130s to make room for the extra bodies that had not been originally planned on the manifest. Left behind at Desert One were five serviceable helicopters, weapons, communications equipment, secret documents and maps...as well as fifty-three hostages in Tehran, a nation's honor, and its pride.

| The crew involved in the Air Force's failed April 25, 1980 attempt to rescue 52 American hostages from the U.S. embassy in Tehran pose in front of their C-130 transport on April 24, 1980, in the Oman desert. The following day, the aircraft was involved in a crash with a Marine Corps helicopter. Top Row (from left): Maj. Richard Bakke, killed; unidentified survivor; Tech Sgt. Joel Mayo, killed; Lyn McIntosh, killed; Maj. Harold Lewis Jr., killed; Capt. Charles McMillan, killed; Staff Sgt. J.J. Beyers, survivor; Col. Jeff Harrison, survivor. Bottom Row: unidentified survivors. (The Associated Press) |

For personal accounts of the survivors, go to Airman Magazine: April 2001, "Desert One" and Airman Magazine: May 2001, "A Night to Remember".

According to Skunk Works Digest "Lockheed C-141B Starlifter of the 437th MAW, MAC, based at Charleston AFB, MS, to extract the Delta Forces and hostages from Manzariyey, two equipped as "hospitals" (one as spare) and one as "airliner". Instead both specially equipped medevac aircraft flown to Masirah, Oman, to evacuate the wounded to Wadi Kena, Egypt, after the aborted mission."

According to an article on Spec War Net: Operation Eagleclaw: What was ultimately decided on was an audacious plan involving all four services, eight helicopters (USMC RH-53's), 12 planes (four MC-130's, three EC-130's, three AC-130's, and two C-141's), and numerous operators infiltrated into Tehran ahead of the actual assault. The basic plan was to infiltrate the operators into the country the night before the assault and get them to Tehran, and after the assault, bring them home.

The first night, three MC-130's were to fly to an barren spot in Iran and offload the Delta force men, Combat Controllers, and translators/truck drivers. Three EC-130's following the Combat Talon's would then land and prepare to refuel the Marine RH-53's flying in from the US Carrier Nimitz. Once the helicopters were refuled, they would fly the task force to a spot near the outskirts of Tehran and meet up with agents already in-country who would lead the operators to a safe house to await the assault the next night. The helicopters would fly to another site in-country and hide until called by the Delta operators.

On the second night, the MC-130's and EC-130's would again fly into the country, this time with 100 Rangers, and head for Manzariyeh Airfield. The Rangers were to assault the field and hold it so that the two C-141's could land to ferry the hostages back home. The three AC-130's would be used to provide cover for the rangers at Manzariyeh, support Delta's assault, and to supress any attempts at action by the Iranian Air Force from nearby Mehrabad Airbase. Delta would assault the embassy and free the hostages, then rendevous with the helicopters in a nearby football stadium. They and the hostages would be flown to Manzariyeh Airfield and the waiting C-141's and then flown out of the country. All the aircraft but the eight helicopters would be flown back, the helicopters would be destroyed before leaving.

What actually happened was far different from what was planned.

A month before the assault a CIA Twin Otter had flown into the first landing area, known as Desert One. A USAF Combat Controller had rode around the landing area on a light dirt bike and planted landing lights to help guide the force in. That insertion went well, with no contact, and the pilots reported that their sensors had picked up some radar signals at 3,000 feet but nothing below that.

Despite these findings, the helicopter pilots were told to fly at or below 200 feet to avoid radar. This limitation caused them to run into a haboob, or dust storm, that they could not fly over without breaking the 200 foot limit. Two helicopters lost sight of the task force and landed, out of action. Another had landed earlier when a warning light had come on. Their crew had been picked up but the aircraft that had stopped to retrieve them was now 20 minutes behind the rest of the formation.

Battling dust storms and heavy winds, the RH-53's continued to make their way to Desert One. After recieving word that the EC-130's and fuel had arrived, the two aircraft that had landed earlier started up again and resumed their flight to the rendevous. But then another helicopter had a malfunction and the pilot and Marine commander decided to turn back, halfway to the site. The task force was down to six helicopters, the bare minimum needed to pull off the rescue.

The first group of three helicopters arrived at Desert One an hour late, with the rest appearing 15 minutes later. The rescue attempt was dealt it's final blow when it was learned that one of the aircraft had lost its primary hydralic system and was unsafe to use fully loaded for the assault. Only five aircraft were servicable and six needed, so the mission was aborted.

Things got worse, though, when one of the helicopters moved to another position and drifted into one of the parked EC-130's (in the pilot's defense, it was dark and his rotors kicked up an immense dust cloud, making it difficult to see). Immediately both the C-130 and RH-53 burst into flames, lighting up the dark desert night. The C-130 was evacuated and the order came to blow the aircraft and exfiltrate the country.

However, in the dust and confusion the order never reached the people who would blow the aircraft. There were wounded and dying men to be taken care of and the aircraft had to be moved to avoid having the burning debris start another fire. Because of this failure to destroy the helicopters, top secret plans fell into the hands of the Iranians the next day and the agents waiting in-country to help the Delta operators were almost captured.

The Aftermath: broken aircraft at Desert One. All told, five Air Force personnel and three Marines lost thier lives and dozens more were injured. The Iranians scattered the hostages around the country afterwards, making any further rescue attempts impossible. They would be released later, after ??? days of imprisonment.

Lessons LearnedInsufficient information and bad planning played a key role in the failure of the rescue. The planners had calculated that it would take the eight RC-53's four hours and twenty minutes to make the flight; it had taken five hours twenty minutes. The Air Weather Service had not been able to predict the low level dust storms that hampered the mission. If they had, some more low-level bad weather flight training might have made the flight easier and have prevented the fatal crash that killed eight people.

Also, the helicopter crews had been thrown together at the last minute after it was discovered that many of the Marine pilots lacked the skills necessary to complete the mission. It was a combination of Air Force, Navy, and Marine pilots who flew the mission. In one case, unfamiliarity with the aircraft caused one pilot to ground the aircraft when it could have flown the mission. Also see Bibliography of Operation Eagleclaw for more sources of information.

8th SOS Aircraft of Operation Eagle Claw The final operation plan - Operation 'Eagle Claw' - involved staging three MC-130 command and communication transport aircraft (including an MC-130E-Y, 64-0565, and an MC-130E-C, 64-0572, of the 8th Special Operations Squadron) together with three EC-130Hs equipped as tankers with wing probes (62-1809, 62-1818 and 62-1857 of the 7th Airborne Command and Control Squadron) to Masirah Island; all these aircraft were upgraded to include T56A-15 engines. Meanwhile USS Nimitz would sail into the Gulf of Oman with eight RH-53D Sea Stallion helicopters of Navy Helicopter Mine Countermeasures Squadron HM-16 embarked from USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63), as the C-141 Starlifters and a C-9 Nightingale transport carrying a hospital and burns unit deployed to Eqypt. A message in Skunk Works Digest from Kathryn & Andreas Gehrs-Pahl on 17 Mar 1997 lists all the Eagle Claw aircraft on supply and tanker missions for deployment to and from Wadi Kena, Egypt.

- 1 Lockheed MC-130E Hercules, COMBAT TALON I, Special Operations aircraft of the 8th SOS 'Black Birds', 1st SOW, TAC, based at Hurlburt Field, FL, used as spare and later returned to Wadi Kena, Egypt, and supposed to be used in Night Two operations (?).

- * 3 Lockheed EC-130H ABCCC aircraft of the 7th ACCS, 552nd AWACW, TAC, based at Keesler AFB, MS, but flown by pilots of the 8th SOS 'Black Birds', 1st SOW, TAC, based at Hurlburt Field, FL. Used as fuel transporter and ground refueller for the RH-53Ds at Desert-I. Selected mainly because they had in-flight refueling capability. Type Call Sign Serial Pilot ------ *

- MC-130E DRAGON-1 ..-.... Capt. Bob Meller flew 1 hour ahead, surveyed and secured the Desert-I landing site, and returned back to Oman after the EC-130Hs arrived; *

- MC-130E DRAGON-2 ..-.... Capt. Marty Jubelt brought felta Force and other personnel to the landing site, and returned back to Oman after the EC-130Hs arrived; *

- MC-130E DRAGON-3 ..-.... Capt. Steve Flemming brought Delta Force and other personnel as well as a SATCOM radio to the landing site, and returned after the accident with helicopter crews and other personnel after REPUBLIC-5 left; *

- Based at Wadi Kena, Egypt: - -------------------------- * 4 Lockheed MC-130E Hercules, COMBAT TALON I, Special Operations aircraft, of the 8th SOS 'Black Birds', 1st SOW, TAC, based at Hurlburt Field, FL, to be used to transport Rangers to the airport at Manzariyey. *

The Guts to Try The following is an Associated Press article on 15 April 2000. 'The guts to try' still inspires 20 years after failed rescue mission

By BILL KACZOR

Associated Press

HURLBURT FIELD -- After the fiery collision of a helicopter and transport plane killed eight servicemen in an Iranian desert, survivors of their ill-fated mission got an unusual message that still inspires 20 years later.

British workers at an airfield on an island off Oman wondered why only five U.S. Air Force C-130s returned on April 25, 1980 after six of the four-engine turboprops had taken off the night before.

They soon realized what happened to the missing plane after hearing news reports of a failed attempt to rescue 52 American hostages from the U.S. embassy in Tehran, recalled retired Col. Roland Guidry, then commander of the 8th Special Operations Squadron.

''They got two cases of cold beer and put them in a jeep and ran them around the edge of the runway to our tent city,'' Guidry said. ''One of them had written on the top case of beer an inscription that said, 'To you all from us all for having the guts to try.' ''

The message was torn off and taken back to Hurlburt where it was framed and put in the squadron's trophy room.

''The Guts to Try'' became the motto of a mission that may have failed but also prompted a buildup of special forces -- focusing on clandestine operations, guerrilla tactics and counter-terrorism -- which later paid off with successes in Grenada, Panama, Iraq and the Balkans.

Improvements were made in aircraft, training, communications, interservice coordination, command structure and tactics. The changes were qualitative and quantitative, said Col. Kenneth Poole, 48, of Anniston, Ala., a navigator aboard one of the surviving C-130s in Iran.

''If I need four airplanes to do an operation I'm going to send six,'' said Poole, now chief of contingency operations for the Air Force Special Operations Command at Hurlburt. ''That's called Iran math.''

Guidry was aboard the lead plane in Iran and then participated in the buildup as chief of air operations for the U.S. Special Operations Command, which was created at Fort Bragg, N.C., as a result of the disaster. The joint command is now at MacDill Air Force Base near Tampa.

''Although I hated to lose five people under my command, we're probably much better off in special operations today, 20 years later, because this mission failed,'' said Guidry, now a real estate broker in nearby Destin. ''It was a wake-up call.''

Five Hurlburt airmen and three Marines died when a Marine helicopter that was trying to take off crashed into a C-130 parked at Desert One, their rendezvous point.

The mission's 20th anniversary will be marked with a memorial service and symposium Thursday at Hurlburt. A ceremony sponsored by the humanitarian group No Greater Love is set for April 25 at Arlington National Cemetery.

The rescue attempt was an audacious plan, code named Eagle Claw, that nearly worked, Guidry said.

Six C-130s landed at Desert One with an Army Delta Force and fuel for eight Navy and Marine Corps helicopters from the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz.

The choppers then were to take the attackers to a hideout near Tehran. The next night, trucks purchased by operatives in Iran, would have taken them to the embassy. Another assault force aboard C-130s would fly to and capture an Iranian airfield.

The helicopters would pick up everyone from the embassy and fly them to the airfield where transport planes would take them out of Iran.

The mission never got that far. One helicopter, struggling to find its way through engine-clogging dust kicked up by a sand storm, turned back. A second was forced down by mechanical problems and another chopper picked up its crew.

One of the helicopters that made it to Desert One also was out of commission, leaving only five. At least six were needed to go on so the mission was aborted.

There were other problems. A bus came by on a dirt road shortly after the lead C-130 landed. Its driver and about 40 passengers were held until the Americans left.

Then a gasoline tanker truck drove up and a soldier, ordered to stop it, blew it up with a rocket, said Chief Master Sgt. Taco Sanchez, of Murray, Ky., then a loadmaster on the lead plane.

''When you look back on it 20 years later it is kind of comical in a way, but at that time it was bloody-ass scary,'' said Sanchez, 46, Hurlburt's top-ranking noncommissioned officer.

It got worse. The helicopters were refueled to fly back to the carrier, but when one lifted off it became engulfed in dust, clipped a C-130's tail and spun into the transport's cockpit area.

''The whole windscreen lit up,'' said retired Staff Sgt. J.J. Beyers, the C-130's radio operator. ''We thought we were being shelled.''

Beyers, 57, of nearby Niceville, tried to go down steps to the cargo bay when something hit him and he blacked out. He came to in the cargo bay and crawled to a door. ''As I got there I stood up and a couple of Delta boys came and got me out,'' he recalled.

Of seven men on the flight deck, only Beyers and a relief pilot standing beside him survived. Three other airmen and dozens of assault troops made it out of the cargo bay.

Retired Air Force Col. John Carney, 59, of Tampa, was a combat air traffic controller watching from 100 yards away as munitions exploded, flames shot from the wreckage and a plume of black smoke billowed into the night sky.

''It was just a scene right out of 'Apocalypse Now,' '' he said.

Bodies were trapped in the burning wreckage and had to be left behind. Iran gave the remains to Swiss officials who turned them over to the United States.

Beyers was the most seriously injured survivor with lung damage and severe burns to his hands. He is permanently disabled and medically retired.

To provide for the education of 15 children left behind by the eight men who died, their comrades created the Special Operations Warrior Foundation. Two of Beyers' six children also were given scholarships.

Carney, the foundation's president, said it has since raised $1 million and provided grants to 347 more children of lost special operations personnel.

The military trained for a second rescue, but it was never attempted. Iran released the hostages after 444 days of captivity in January 1981 as Ronald Reagan was sworn in as president.

The C-130 crews straggled back to Hurlburt with their ''guts to try'' memento instead of the hostages they hoped to rescue.

''It was the right thing to do,'' Sanchez said. ''Did we do it? No. But I can tell you that if we had the same mission today we'd prosecute it 100 percent and we'd bring 'em home.''

Honoring the Heroes of Operation Eagle Claw The following was extracted from the Air Force Magazine: April 2001Remembering heroes

April 2001

Eight men died during the aborted attempt to rescue American hostages held captive in Iran. Five of them were airmen from the 8th Special Operations Squadron at Hurlburt Field, Fla. Three were Marine helicopter crewmen.

“Take solace in the fact [that] what they did only a few could even attempt,” said Lt. Gen. Norton Schwartz, the commander of Alaskan Command, at a 20th anniversary commemorative ceremony at Hurlburt Field, Fla. “What they did was keep the promise. They had the guts to try.”

Schwartz was a pilot in the 8th SOS at the time of the rescue mission and went on to command Hurlburt’s 16th Special Operations Wing.

Another special operator and now chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Hugh Shelton, expressed similar sentiments during a speech at an April 2000 ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery honoring those killed.

“The sheer audacity of the mission, the enormity of the task, the political situation at the time. When I reflect on the results — both positive and negative — I’m awed,” Shelton said.

“The very soul of any nation is its heroes. We are in the company of giants and in the shadow of eight true heroes,” he said.

Those heroes are Capt. Richard L. Bakke, 33; Capt. Harold J. Lewis, 35; Capt. Lyn D. McIntosh, 33; Capt. James T. McMillan II, 28; Tech. Sgt. Joel C. Mayo, 34; Marine Staff Sgt. Dewey L. Johnson, 31; Marine Sgt. John D. Harvey, 21; and Marine Cpl. George N. Holmes Jr., 22. — Master Sgt. Jim Greeley

As a footnote, on December 19, 2001 the U.S. House of Representatives has passed a bill naming a new Post Office in Valdosta for Air Force Major Lyn David McIntosh, who lost his life during a mission in 1979 to rescue 66 Americans held hostage at the U.S. Embassy in Iran. President Bush signed it into law.

Operation Urgent Fury Combat, Grenada (24 Oct–3 Nov 1983): The squadron was called on again in October 1983 to lead the way in the rescue of American students endangered on the island of Grenada. After long hours of flight, the aircrew members faced intense ground fire to airdrop Army Rangers on time, on target. They subsequently followed up with three psychological operations leaflet drops designed to encourage the Cubans to discontinue the conflict.

The Rangers had little time to prepare for their role in Urgent Fury. Within hours of receiving orders to move, Ranger units were marshaling at Hunter Army Airfield, Georgia, prepared to board C-130s and MC-130s for the ride to Grenada.

The invasion in the south focused on an unfinished runway at Point Salines, located on the island's most southwestern point. While securing the airfield, Rangers were to secure the True Blue Campus at Salines, where American medical students were in residence. As quickly as possible, Ranger units were then to take the army camp at Calivigny. A Navy SEAL team which was to have provided intelligence on the airfield at Salines was unable to get ashore. At 0534 the first Rangers began dropping at Salines from 8th SOS MC-130E and other C-130s, and less than two hours elapsed from the first drop until the last unit was on the ground, shortly after seven in the morning. After the rangers had secured the runway, 800 more troops would land, freeing the rangers to press northward where they were to secure the safety of American medical students and bring under control the capital of St. Georges. At the end of the first day in Grenada, the Rangers had secured the airfield and True Blue Campus at a cost of five dead and six wounded. Once the Rangers had secured the runway, elements of the 82nd Airborne Division landed, and late in the evening of the 26th the 82d Division's 3d Brigade began to deploy across the island. In the north, 400 Marines would land and rescue the small airport at Pearls.

Painting of MC-130E Ranger air drops

According to Operation Urgent Fury, "The 8th Special Operations Squadron ... was called on again in October 1983 to lead the way in the rescue of American students endangered on the island of Grenada. After long hours of flight, the aircrew members faced intense ground fire to airdrop U.S. Army Rangers to Point Salinas Airfield in the opening moments of Operation Urgent Fury. They subsequently followed up with three psychological operations leaflet drops designed to encourage the Cubans to discontinue the conflict."

It continued, "In regard to PSYOP in Grenada, Stanley Sandler says in Cease Resistance: It's Good for You: A history of U.S. Army Combat Psychological Operations, 1999. "4th PSYOP Group loudspeaker teams attached to the 82nd Airborne Division, in addition to persuading significant numbers of frightened Peoples Revolutionary Army (PRA) troops to turn themselves in, confirmed the enemy's low morale as well as the desire of even some of the Cuban "Construction Battalions" to remain on the island with their Grenadian wives and families."

Regarding leaflets, Sandler says, "But other, more specialized leaflets, emphasized that this was a combined operation with other Caribbean nations as well as the United States acting against a foreign threat. Something new was added when U.S. PSYOP troops photographed captured Grenadian Communist leaders in captivity, thus reassuring citizens that they could now go about their business unmolested by a cabal whom most genuinely feared. One such leaflet, headlined "These hoodlums are now in custody," displayed most unflattering photos of the subjects while another showed the two chiefs of the Marxist clique, Bernard Coard and Hudson Austin, in safe custody on a U.S. Navy ship with the message "Former PRA members: Your corrupt leaders have surrendered. Knowing resistance is useless...Join your countrymen now in rebuilding a truly democratic Grenada."

Sandler says in an article printed in Mindbenders, Vol. 9, No.3, 1995: "The 4th PSYOP Group distributed leaflets giving the Grenadian population guidance and information, and a newly-deployed 50-kilowatt transmitter, "Spice Island Radio," broadcast news and entertainment throughout the island.

Radio Free Grenada was one of the first targets of American bombs. To replace Radio Free Grenada, the U.S. set up Spice Island Radio, under the overall control of the Psychological Operations Section of the Army. A twelve-man team of Navy journalists immediately flew in from Norfolk, recruited some local announcers, and Spice Island Radio was on the air. Their first broadcast called on Grenadians to lay down their arms. The head of the Navy team, Lt. Richard Ezzel, told Reuters, "We wanted to save lives."

Department of the Army FM 33-1, Psychological Operations, July 1987, mentions the Grenada PSYOP campaign. "The 1983 Grenada operation included PSYOP elements from all the services. These elements provided the commander with the primary means of mass communication with both the enemy and local populace. The communication capability was especially important during the initial phases of the operation.

Leaflets directing the populace to remain indoors and tune their radios to a specific frequency were designed by the Army and printed aboard Navy ships. Other leaflets, produced both at Ft. Bragg and on the island, were effectively used during the consolidation operations to encourage Grenadian civilians to report information concerning Peoples Revolutionary Army (PRA) and Cuban soldiers. An Air Force airborne transmitter station was used by PSYOP elements to broadcast information after the Grenada radio station was rendered inoperative during the first day of operation. By the third day, a small land-based PSYOP station commenced operations. Later, Army PSYOP elements deployed a large 50KW transmitter capable of broadcasting to the entire island. Eventually, PSYOP personnel were broadcasting 11 hours per day."

For more details on the Operation go to FAS: Operation Urgent Fury

Operation Just Cause Panama (20 Dec 1989–14 Jan 1990): Members of the 8th SOS were mobilized in December 1989 as part of a joint task force for Operation Just Cause in the Republic of Panama. 3 MC-130Es from the 8th SOS Black Birds were part of the US flying units of Operation "Just Cause" SOCOM ("Joint Task Force South") under the 23rd Air Force. From late December 1989 to early January 1990, 23 AF participated in the re- establishment of democracy in the Republic of Panama during Operation JUST CAUSE. Special operations aircraft included active and AFRES AC-130 Spectre gunships, EC-130 Volant Solo psychological operations aircraft from the ANG, HC-130P/N Combat Shadow tankers, MC-130E Combat Talons, and MH-53J Pave Low and MH-60G Pave Hawk helicopters. Special tactics combat controllers and medics provided important support to combat units during this operation. Spectre gunship crews of the 1 SOW earned the Mackay Trophy and Tunner Award for their efforts, a 919 SOG Spectre crew earned the President’s Award, and a 1 SOW Combat Talon crew belonging to the 8th SOS ferried the captured Panamanian President, Manuel Noreiga, to prison in the United States. Likewise, the efforts of the 1 SOW maintenance people earned them the Daedalian Award.

According acig.org The attack was initiated by two F-117As, which around 23:00hrs local time dropped two GBU-24s in front of Noriegas HQ at Rio Hato. This operation later caused much discussions, as it was declared for a failure by the public, while the bombs fell right where they were expected to do as the intention was for them to create confusion. Nevertheless, instead of creating confusion, the bombs alerted the Panamese, and when the 13 C-130s loaded with troops of the TF „Red“ arrived over Rio Hato they were confronted by the fire from several ZPU-4 heavy machine guns, caliber 14.7mm. Before the two escorting AC-130s could intervene, the 8th SOS MC-130E that lead the formation of Hercules‘ was obviously hit by ground fire and forced to make an emergency landing with only three engines in working order. The Gunships – soon after jointed by two AC-130As each from the 711th and 919th SOS AFRes, which took off from Howard AFB – then started suppressing the air defenses and this made it possible for the Hercules transports to disgorge rangers from a level of only 600ft/200m. Due to a number of heavily-loaded troopers landing on the concrete runway, 35 of them were injured, but in general they managed to swiftly recover and attack the main terminal of Rio Hato, which was secured by 0153hrs of 20 December. Shortly after the first transports started landing there, bringing reinforcements and evacuating casualties. During this attack the rangers lost two killed and 27 injured (in addition to 35 troops injured during the landing), while the PDF lost 34 killed and 260 captured. The TF „Red“ – now supported by several AH-64As and AH-6s flown in from Howard AFB, and the two 711th SOS AC-130As – then started preparing for its next task. The following was excerpted from and adds to the confusion....a flight of darkened MC-130 Combat Talons and C-130E Hercules STOL turboprop aircraft approach at 500 feet... standing in the door are sticks of U.S. Army Rangers stooped over rucksacks so heavy, it takes both hands to lift and drag them to the jump doors....The Rangers are so encumbered by equipment that they cannot even stand up straight. Approaching their dark target, the GREEN LIGHT COMES ON, through the open jump doors they see red and green tracer fire below. The Rangers strain out the jump doors, some without reserve parachutes: a towed jumper caught by this overload of equipment on the edge of the jump door could get dragged through the air---- if cut away falls to his death....if pulled in, he may be a bloody pulp as he bangs against the side of the aircraft if those still inside wait until everyone jumps; if pulled in early, he blocks the door so Rangers cannot join the battle below to help win it.

A C-130E Hercules pilot writes:

"I saw your web page as a link from the 75th Ranger Reg't page. I flew in Panama, dropping Rangers in Rio Hato, point of fact, we were a 17 ship formation of C-130Es, there were no MC-130s in the airdrop at Rio Hato. When we left from Ft Benning or Panama, the weather was crap and we were overloaded to the point had we lost one engine we would likely have become a smokin' hole. We weighed less than the maximum published wartime weight, but that weight is based on sea-level standard day (59 degrees F) takeoff. When it's cold, that's usually better unless you have to steal engine power to keep the ice off the wings."

General NoriegaOn 3 January 1990, the majority of the force redeployed, but a small element remained behind. During the evening of 3 January, two MH-60s from the 160th transported General Noriega from the Papal Nuncio to Howard AFB for transload to a waiting MC-130 and transport to the United States.

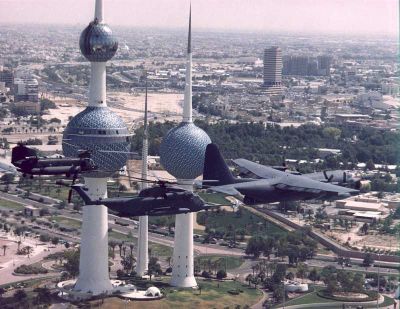

Operation Desert Shield (August 1990-Jan 1991) Operation Desert Shield commenced in August 1990 when Iraq invaded Kuwait. The 8th SOS was deployed to Saudi Arabia as a deterrent against the Iraqi threat to its southern neighbor.

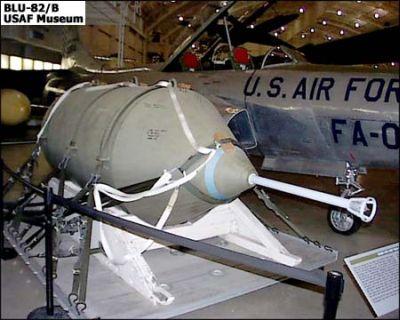

Operation Desert Storm, Southwest Asia, (16 Jan-17 Mar 1991) In January 1991, when Iraq failed to comply with United Nations directives to withdraw from Kuwait, the proven skills of the 8th SOS were called on once again as Desert Shield escalated into Desert Storm. The 8th SOS played a pivotal role in the success of coalition forces as they liberated Kuwait by dropping eleven 15,000 pound BLU-82 bombs and 23 million leaflets and conducting numerous aerial refuelings of special operations helicopters.

Its primary mission was Psyops operations. One third of all airdrops in the first three weeks of Desert Storm were flown by Talons.

The Talons can also be rigged to let loose one of the Air Force's largest bombs, the BLU-82, roughly the size of a Volkswagen Beetle and weighing about 15,000 pounds, or to release propaganda and warning leaflets.

Its secondary mission was search and rescue behind the lines. The Talons can be used to refuel the Pave Lows and other helicopters or sneak behind enemy lines to deliver ground forces, vehicles and supplies.

During the Vietnam War, the USAF used 10,000-lb. M121 bombs left over from World War II, to blast Helicopter Landing Zones (HLZ) in the dense undergrowth. As the supply of M121 bombs dwindled, the USAF developed the Bomb Live Unit-82/B (BLU-82/B) as a replacement. Weighing a total of 15,000 lbs., the BLU-82/B was essentially a large thin-walled tank (1/4-inch steel plate) filled with a 12,600-lb. explosive "slurry" mixture. The designers optimized this bomb to clear vegetation while creating little or no crater, and it cleared landing zones about 260 feet in diameter-just right for helicopter operations. Since only cargo aircraft could carry them, C-130 crews delivered the BLU-82/B with normal parachute cargo extraction systems. The BLU-82/B first saw use in Vietnam on March 23, 1970. Throughout the rest of the war, the USAF used them for tactical airlift operations called "Commando Vault." After the war, the BLU-82/B was used during the Mayaguez rescue in May 1975, but the remaining BLU-82/Bs went into storage until the mid-1980s, when the Air Force Special Operations Command began using them again in support of special operations. During Operation Desert Storm, MC-130E "Combat Talon" aircraft from the 8th Special Operations Squadron dropped 11 BLU-82/Bs, primarily for psychological effects. The USAF used these weapons against terrorist strongholds in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. (WPAFB USAF Museum)

(SITE NOTE: In March 2003, the 21,000lb superbomb was announced. It is an upgrade of the BLU-82. It contains 21,000lb of conventional high explosive, an increase from the 15,000lb BLU-82 "daisy cutter" used at least four times on tunnels and caves in Afghanistan. The warhead is packed with Gelled Slurry Explosive, which is detonated with a high explosive booster. The slurry is poured into the bomb's casing which is then loaded on to a plane and launched by parachute at 6,000ft. There is not yet much public information available about the MOAB (Massive Ordnance Air Burst). It weighs 21,500 pounds, compared to the 15,000 pound Daisy Cutter, and is the size of a small truck. Like the Daisy Cutter, the MOAB is designed to be dropped out of the back of a C-130 aircraft, but can possibly be dropped from a C-17 aircraft, as well. Unlike the Daisy Cutter, which is a free-fall (dumb) bomb, that descends attached to a parachute, the MOAB is a precision bomb guided by GPS (Global Position Satellite). After being pulled out of the cargo hold of the aircraft by a parachute, the parachute releases, and the GPS guides the bomb to the target destination. At a designated altitude, the MOAB sprays the area with a highly flammable mist, which is then ignited by a conventional explosive within the bomb. The results are a truly devastating explosion that can destroy tanks, buildings, and personnel in an area of several hundreds of meters.) (See C-130 Bombers for BLU-82 in Vietnam.) |

Extracted from Source: Unknown The men of the Eighth Squadron believed that the BLU-82 bomb could send an even more powerful message. In the early-morning hours of Feb. 7, Maj. Charles Bingington's MC-130E Combat Talon cargo plane lumbered off the runway. In its belly sat the massive bomb. Behind Major Bingington, a companion plane lifted off, carrying another BLU-82 (Bingington and his wingman became known as the Blues Brothers).

The day before, their target area had been rained with leaflets warning the soldiers below: "Tomorrow if you don't surrender we're going to drop on you the largest conventional weapon in the world." The Iraqis who dared to sleep that night found out the allies weren't kidding. The explosion of a Daisy Cutter looks like an atomic bomb detonating. In the southwest corner of Kuwait that night, an enormous mushroom cloud flared into the dark. Sound travels for miles in the barren desert, and soon Iraqi radio nets along the border crackled with traffic. Col. Mike Samuel, Schwarzkopf's special-operations commander, cabled a message back to the U.S. Special Operations Command headquarters in Florida: "We're not too sure how you say 'Jesus Christ' in Iraqi." A British SAS commando team on a secret reconnaissance mission near the explosion frantically radioed back to its headquarters: "Sir, the blokes have just nuked Kuwait!"

The next day a Combat Talon swept over the bomb site for another leaflet drop with a follow-up message: "You have just been hit with the largest conventional bomb in the world. More are on the way." The victims below didn't need much more convincing. The day after the BLU-82 attack, an Iraqi battalion commander and his staff raced across the border to surrender. Among the defectors was the commander's intelligence officer, clutching maps of the minefields along the Kuwait border. The intelligence bonanza enabled Central Command officers to pick out the gaps and weak spots in the mine defenses. When the ground war began Marine and allied forces breached them within hours.

The bombs cost about $27,000 each. They are dropped from a C-130 cargo plane flying at least 6,000 feet off the ground, to avoid the bomb's massive shock wave. Each is more than 17 feet long and 5 feet in diameter - about the size of a Volkswagen Beetle but far heavier. The MC-130s dropped the BLU-82s again to breach holes in the minefields around Kuwait prior to the assault.

Operation Restore Hope, Somalia (9 Dec 1992 - 4 May 1993) ???? 16th SOW involved, extent unknown. Uncertain if 8th SOS MC-130E/H involved. Operation Restore Hope in Somalia proved to be one of the most diverse humanitarian operations undertaken by US military forces; it quickly highlighted the need for better interagency coordination. President Bush Sr. authorized the operations. In Somalia the military was challenged to coordinate the activities of "49 different UN and humanitarian relief agencies--none of which were obligated to follow military directives." By March 1993, mass starvation had been overcome, and security was much improved. At its peak, almost 30,000 US military personnel participated in the operation, along with 10,000 personnel from twenty-four other states. Despite the absence of political agreement among the rival forces, periodic provocations, and occasional military responses by UNITAF, the coalition retained its impartiality and avoided open combat with Somali factions. However, once President Clinton was inaugurated he stated his desire to scale down the U.S. presence in Somalia, and to let the U.N. forces take over. In March 1993 the U.N. officially took over the operation, naming this mission UNOSOM – II. This precipitated the turmoil to follow. For the military action in the Battle of Mogadishu, go to FAS: Restore Hope for details.

Operation Provide Promise, Bosnia (3 July 1992-9 January 1996) According to Special Operations.com, "The U. S. Air Force relies on the proven abilities of the 8th SOS as evidenced by its recent deployments in support of Operations Provide Promise and Deny Flight in Bosnia."

Provide Promise, which had begun on 3 July 1992, was the international response to an ethnic civil war in Bosnia-Herzegovina in which efforts by Muslims and Croats to secede from Yugoslavia and establish an independent Bosnia were violently resisted by Bosnian Serbs--clandestinely aided by Yugoslavia--who attempted to establish a Serbian republic of Bosnia.

(NOTE: Still researching this item. (Source: FAS: 8th SOS.) Uncertain of MC-130 involvement -- perhaps as Psyops. Possible OPERATION ALLIED FORCE when an MC-130 supported the rescue operation for the downed F-117A pilot.)

Operation Deny Flight, Bosnia (12 April 1993 - 21 December 1995) According to Special Operations.com, "The U. S. Air Force relies on the proven abilities of the 8th SOS as evidenced by its recent deployments in support of Operations Provide Promise and Deny Flight in Bosnia." (Additional Source: FAS: 8th SOS.)

Deny Flight enforced the no-fly zone, provided close air support to UN troops, and conducted approved air strikes under a "dual-key" command arrangement with the UN. NATO Airborne Early Warning and Control (AWACS) aircraft began monitoring operations in October 1992, in support of UN Security Council Resolution 781, which established a no-fly zone over Bosnia-Herzegovina. Data on possible violations of the no-fly zone has been passed to the appropriate UN authorities on a regular basis.

NATO's Deny Flight operation, enforcing the no-fly zone over Bosnia, terminated on December 20, 1995, when implementation force (IFOR) assumed responsibility for airspace over Bosnia. Operation Deny Flight transitioned to Decisive Endeavor/Edge in support of the IFOR Operation Joint Endeavor.

(NOTE: Still researching this entry. Records of U.S. aircraft indicates only 3 x USAF EC-130 Airborne Battlefield Command and Control Center aircraft at Aviano AB, Italy; 2 x USAF EC-130 electronic warfare aircraft at Aviano AB, Italy; 2 x USAF AC-130 Gunship aircraft at Brindisi AB, Italy. No mention of 8th SOS MC-130s. (Source: AF South Fact Sheet.))

Operation Assured Response, Liberia (9 April - 18 June 1996) According to Special Operations.com, the 8th SOS was deployed on Operation Assured Response. In 1996, the US Military assisted in safeguarding and evacuating Americans from Liberia when that nation's civil war reignited into factional fighting and general violence in Liberia." During the first week of April 1996, as a result of intense street fighting during the ongoing civil war in Liberia, about 500 people sought refuge on American Embassy grounds and another 20,000 in a nearby American housing area. On April 6, the president approved the US ambassador's request for security, resupply and evacuation support.