8th Tactical Bomb Squadron

(1964-1969) |

Acknowledgment: B-57B: Special thanks to Joe Baugher sites for its detailed information on the B-57B in Vietnam. Special thanks to Marquis Witt and his B-57 Canberra.org site for its exceptional materials dealing with the B-57B. (Special thanks for the Doom Pussy story by Bob Galbreath; The Guns of Tchepone story by Larry Mason, Jere Joyner, Bob Mikesh, and Joe Rup, Jr. and weapons loader narratives by Dan English.) Special thanks to Gene Bonham for his photos and narratives on the B-57s at Phan Rang. A-37B: We are extremely grateful to A-37 Association website for its stories and photos. Thanks to Dennis Selvig for his A-37 anecdotes. Thanks to Richard Dutcher and James Lamb for their photos on the A-37 Association website. Special thanks to William R. Stevens, MSgt, USAF (ret) for his photos as a Line Chief/"B"

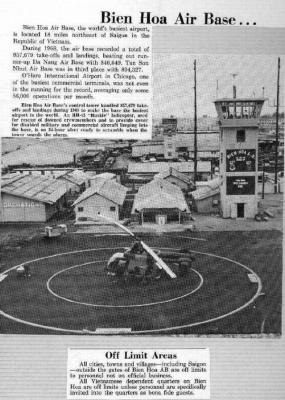

Flight Chief, 8th SOS (Dec 71-Nov 72). Thanks to Earl Watson for his photos as part of a load crew (72-73). Thanks to the AGE Ranger site (Darryl W. Clark, CMSgt, USAF) for its photos of the 8th AGE Shop at Bien Hoa. Thanks to Wavelen Wayne Fielder at Det 6 600th Photographic Squadron for his photos of Bien Hoa (APPROVAL PENDING). Other sources include: Air War College: 25th ID After Action Report; Easter Offensive: by W. R. Baker; Paper: They were Good Ol' Boys; VNAF.net,. Lastly we are deeply indebted to the historical information found at Air Force Historical Research Agency (AFHRA) on line.  8th Bomb Squadron insignia 8th Bomb Squadron insignia

Approved June 21, 1954 (KE 8387)

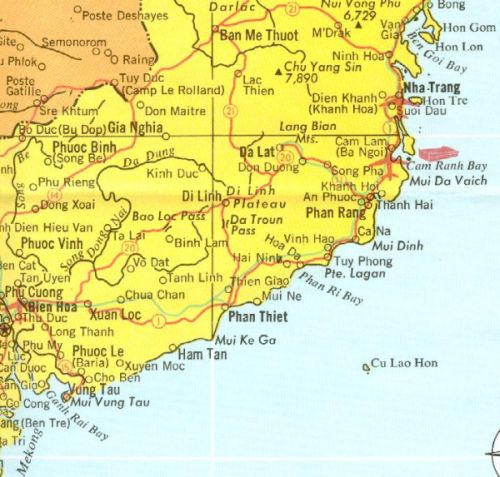

1968 Map of Vietnam & Chronological History (1968-1973)

Bien Hoa and Phan Rang Location in Vietnam (1968 Map)The following is from Historical Text Archive: Don Mabry: Nixon widened the war, however. He defined victory as the preservation of a non-Communist government in Saigon. To achieve victory, he adopted measures long advocated by the military but rejected by Johnson. In March, 1970, Prince Sihanouk of Cambodia was overthrown, probably by the CIA and the right-wing General Lon Nol took his place. North Vietnamese troops poured into interior Cambodia. On April 30, 1970 Nixon ordered the invasion of Cambodia. Although the US had been secretly fighting there, this invasion was a widening of the war. The Cambodian invasion sparked serious protests. The anti-war movement had been quiet for most of 1969, giving the new president a honeymoon as he began implementing his "secret plan." In October, 1969, the Vietnam Moratorium Committee brought 500,000 to Washington, DC to protest the war and encourage Nixon to end it. The Nixon administration condemned the protest meeting. It indicated that anti-war sentiment had grown substantially. Nixon became even more anxious to win the war. When Cambodia was invaded in April and May, 1970 one and one-half million students protested on 1200 campuses. On May 4th, four students, on their way to class, were murdered by National Guard troops who had been called into action by the governor because of the anti-war demonstrations on the Kent State campus. On May 14th, two Jackson State students were murdered by Mississippi Highway Patrol officers who fired on a dormitory when students there protested the war and racism. Many Americans were outraged while many others believed that the students had asked for it. These incidents were further evidence of how the war was tearing the nation apart. Congress began raising questions about the constitutionality of the invasion and repealed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, one of the few legal props for the war.

The Cambodian invasion failed to cut off North Vietnamese and Viet Cong progress and Congress refused to fund Nixon's planned invasion of Laos. In February, 1971, Nixon used US air power to support a South Vietnamese invasion of Laos. This, too, failed.

As US troops were being withdrawn, Nixon stepped up the use of US air and naval power. From 1969 to the end of 1971, the US had dropped 3.3 million tons of bombs on South Vietnam, North Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, more than Johnson had dropped in five years and more than the US had dropped on Europe and the Pacific in World War II. Nixon was trying to bomb the enemy into submission but it did not work. In the Spring of 1972, North Vietnamese forces launched an offensive which pushed back South Vietnamese forces. Nixon widened the bombing of North Vietnam and mined its harbors but the war was lost. The Nixon administration had been engaging in secret negotiations between 1969 and 1971 as Henry Kissinger made thirteen trips to France to meet with North Vietnamese diplomats. The US proposed a cease fire in advance of any political settlement and the preservation of the Thieu regime. Nixon had asserted that Thieu was one of the four or five greatest political leaders of the world, and supported Thieu in the 1971 presidential election, one so fraudulent that all of his opponents withdrew. But in 1972, shortly before the US presidential election, Nixon announced progress towards a cease fire. The war ended in 1973. Nixon resigned in 1974 so he did not preside over the rout of the South Vietnamese in 1975 when the North Vietnamese armies took over the entire country.

The war was costly. One and one-half million died in Indochina of whom 58,000 were Americans. Millions more were maimed. Some 500,000 people became refugees. From 1965-1971, the US spent $120 billion dollars directly on the war but other costs raised this amount to $400 billion. Costly, too, was its effect on the US military which thought itself invincible and had difficulty accepting the fact that it was not. Of course, the War of 1812 was a draw, at best, but Americans only paid attention to recent events. It was a long war but not as long as the War on Drugs or the perpetual war that the War on Terrorism promises to be. It left open wounds on the US psyche. (See Base Development in South Vietnam 1965-1970: Chap 10: Base Camps for Base Camps information.)

- 1970

- Feb. 20: Nixon aide Henry Kissinger begins secret peace talks in Paris.

- April 29: U.S. forces enter Cambodia to clear North Vietnamese sanctuaries.

- April: U.S. Air Force bombs Cambodia.

- May 4: National Guardsmen kill four students at Kent State University in Ohio during anti-war protest.

- 1971

- Nov. 12: Nixon announces that U.S. ground forces are in defensive role; offensive actions handled by South Vietnamese.

- 1972

- April 15: U.S. Air Force resumes bombing of Hanoi and Haiphong after four-year lull.

- April 15-20: Hundreds protesting bombing arrested across the country.

- July 8: Actress and anti-war campaigner Jane Fonda visits Hanoi.

- Nov. 7: Nixon re-elected.

- Nov. 20-21: Kissinger and Le Duc Tho hold more private peace negotiations.

- Dec. 13: Paris talks deadlock.

- Dec. 18-29: "Christmas Bombing" of Hanoi and Haiphong by Air Force.

- 1973

- Jan. 15: Nixon halts U.S. offensive actions against North Vietnam.

- Jan. 27: Peace pact signed in Paris by United States, South Vietnamese, Viet Cong and North Vietnamese.

- March 29: Withdrawal of American troops and release of 590 U.S. war prisoners completed.

8th Special Operations Squadron Squadron

(1969-1972) |

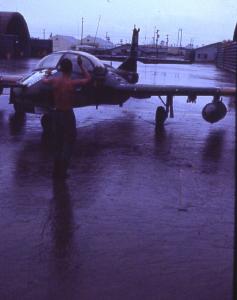

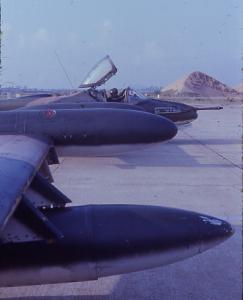

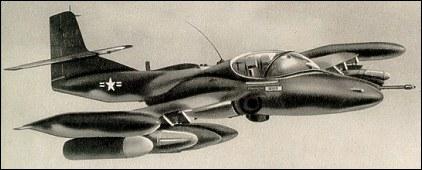

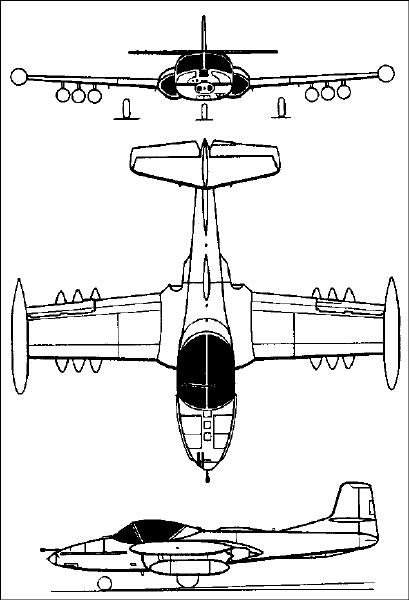

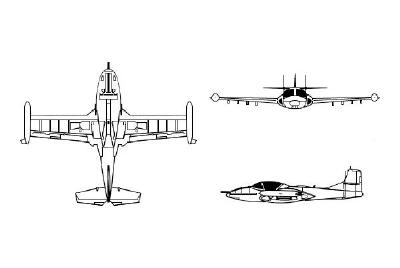

3rd TFW A-37

(USAF Photo)

Convert to A-37B Dragonflys: Combat Dragon (1967) There was a great need for close air support (CAS) as well as counter-insurgency support aircraft as more troops were thrown into the battles of Vietnam. This in turn led the aging A-1E "Spad" to be exposed to more lethal fire resulting in increased losses. Early on in 1965, the USAF had tried the B-26K Invader but soon structural problems caused the wings on some aircraft to fall off. The B-57s were used as strike aircraft but of the 94 aircraft in the area, 51 were lost in combat (including 15 on the ground). Soon the aircraft losses became critical. By Jul 69 only 8 B-57s were left. The decreasing number of A-1Es impacted the support the ground troops. The F-4s and F-105s were only moderately effective as they could not operate effectively in close proximity bombing to ground troops.

The USAF began to revamp the COIN (counter-insurgency) program involving the YA-37A that the USAF had initially been shelved. In fact, the YA-37A that had been sent to the USAF Museum was removed from the museum and sent to Cessna for repair as the wing wiring had been cut for placement into static display status. New wing wiring was installed and the YA-37 easily passed its flight tests. The decision was made by Cessna to convert 39 existing airframes from the bone-yard at MASDC/Davis-Montham AFB, AZ. These airframes were the earliest T-37 trainers.

According to From Trainer to Gunfighter: The A-37

As soon as they had been airtested the converted 'Tweets' were flown to England AFB where both air and ground crews began their training. Eventually 24 had been delivered and they and their crews had been deemed fit to undertake the assigned test codenamed 'Operation Combat Dragon'. Role envisaged for the A-37A included Close Air Support, Armed Recconnaisance, Helicopter Escort and any other duties that would be assigned in theatre.

As well as the eight underwing pylons cleared for a variety of stores the Dragonfly sported a 7.62 mm minigun in the nose plus associated gunsite on the cockpit coaming. To complement their new role one half of the new fighter batch were painted in an experimental scheme of off-white and light blue whilst the remainder wore the by now standard Vietnam scheme of two shades of green and tan uppers with light grey lower surfaces. The blue and white aircraft were later repainted into the normal scheme as the camouflage proved to be too effective. (SITE NOTE: Pilot comments on the blue-white paint scheme were that it was not any more effective in preventing ground fire damage than the camouflage paint scheme, but did pose a problem as wing men and FACs had a difficult time spotting the aircraft from the air.)

By the end of July 1967 all the required aircraft for the 604th Air Commando Squadron Designate had been crated and were ready for trans-shipment to Vietnam in C-141 transports. The 604th ACS was moved to Bien Hoa Air Base, South Vietnam. It remained there for Combat Dragon between 17 July and 14 August 1967. (SITE NOTE: There seems to be differing quotes as to the exact start dates of various phases with dates differing by a few days to a month. This is not considered significant for this history's purposes.) According to AF Museum: Cessna A-37A: On 23 August 1966, the USAF directed the establishment of a program to evaluate the A-37 in a combat environment. The project was named "Combat Dragon" and was designed to test the effectiveness of the A-37 in Close Air Support, Counterinsurgency and escort missions in Vietnam. Besides testing the aircraft operationally, the project was also used to evaluate the maintenance, supply and manpower requirements. The Tactical Fighter Weapons Center directed the program and established a 350-man squadron with 25 A-37A's at England AFB, Louisiana in early 1967. The unit was designated as the 604th Air Commando Squadron (ACS). Initial instructor pilot training began on 29 March 1967, initial operations and combat orientation started on May 1st.

Phase I of "Combat Dragon" was done between 19 June and 16 July 1967 at England AFB. Phase I measured data collection and analysis procedures to be used during the actual combat evaluation, train the A-37A pilots, establish a bombing and gunnery baseline, and identify and fix problems with the aircraft.

On 26 July 1967, the 3rd Tactical Fighter Wing at Bien Hoa Airbase received its first Cessna A37A Dragonfly aircraft under project "Combat Dragon." The attack version was considerably heavier than the T37B trainer from which it was developed. Americans were to fly the A37, nicknamed "Tweet," while the aircraft was being readied for the Vietnamese Air Force. The Dragonfly was essential to plans to bring the VNAF up to strength with a tactical force that was almost all-jet.

Phase II of "Combat Dragon" began on August 15th and ended on September 6th. This phase of the project was used to familiarize the pilots was the operational areas of Vietnam and Laos. The data collection and evaluation system was also refined using forms and methods already in use in Southeast Asia.

Phase III of "Combat Dragon" began on September 7th and the first actual ground strike missions were flown. Phase III operations continued until 27 October.

Phase IV of "Combat Dragon" was done between October 28th and 30th and tested accelerated (maximum sortie generation) mission scheduling.

Phase V began on November 1st and tested the ability of the aircraft to operate from a forward operating location. Seven aircraft were deployed to Pleiku Air Base and flew combat mission through December 2nd. The remaining 18 aircraft remained at Bien Hoa AB and flew normal (Phase III) combat strike missions. The 604th Air Commando Squadron pilots initiated its Phase III combat operations test on Aug. 15, 1967, flying 12 combat sorties a day in support of ground troops and against enemy supplies being shipped into South Vietnam. The daily sortie reached 60 by the end of September.

In October, some of the planes were shipped to Pleiku for Phase V of the tests where pilots began flying armed and visual reconnaissance missions and night interdiction flights in Tiger Hound. Tiger Hound was an area roughly 90 miles long in Laos bordering on South Vietnam territory used by the North Vietnamese to infiltrate troops and supplies. It was also the code name of a special Air Force, Navy, Marine and Army task force that began interdicting southeastern Laos.

When the testing period drew to a close, the Dragonflies had logged more than 4,000 sorties without a single combat loss. One plane went down as a result of an unfortunate maneuver after the aircraft returned to its home base. The squadron was then attached to the 14th Air Commando Wing at Nha Trang. The unit however, continued to fly out of Bien Hoa.

(See Jim Fattaleh's A-37 Photos for photos 1967-1968, 604th ACS, Bien Hoa, RVN.)

Based upon the recommendations of the Combat Dragon tests, the A-37B was designed. The first A-37B arrived at Hurlburt Field in December 1969 for the 603rd Special Operations Squadron.

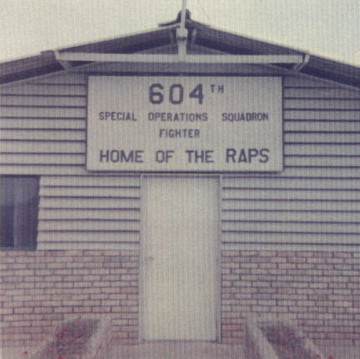

604th ACS attached to Bien Hoa (1967) The 604th Air Commando Squadron had used the A-37 aircraft with great effect in close air support missions dropping high explosives and napalm. The motto on the signs read, "Closest Air Support" -- "Smallest Fighter; Fastest Guns."

Though assigned to the 14th SOW at Phan Rang, the 604th was based at Bien Hoa and came under the operational control of the 3rd TFW. Operations began almost immediately. According to pilot reports, the aircraft was somewhat hard to control when fully laden -- and very difficult to control on pullout if only one wing's stores dropped. "Once trimmed to a lower weight was a delight to fly. Agile accurate it was the FAC's dream-the Army on the ground grew to love it and their enemies to fear it."

SITE NOTE: From AFHRA: 14th Flying Training Wing: "14th SOW: Performed combat operations in Southeast Asia, Mar 1966–Sep 1971, operating from numerous locations in South Vietnam and Thailand. Operations included close and direct air support, interdiction, combat airlift, aerial resupply, visual and photographic reconnaissance, unconventional warfare, counterinsurgency operations, psychological warfare (including leaflet dropping and aerial broadcasting), forward air control operations and FAC escort, search and rescue, escort for convoy and defoliation operations, flare drops, civic actions, and humanitarian actions. The wing also operated Nha Trang AB, South Vietnam, Mar 1966–Oct 1969, and provided maintenance support for a number of tenants. Trained South Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF) personnel in AC–119 operations and maintenance, Feb–Aug 1971, and transferred some of its AC–119s to the VNAF, Aug–Sep 1971 as part of a phase-down for inactivation." The A-37A had exceptional loiter times unmatched by its larger F-100 Huns and F-4 Phantom cousins. With external fuel tanks on the inboard pylons and a load of napalm and HE bombs the A-37A, the A-37A was able to hit a target and loiter in the area awaiting another target from the FAC. The larger jets had to burn off fuel to launch their strike; and after the strike, they required a refuel. On the other hand, the A-37A had none of these limitations and could launch a strike immediately -- loiter in the area because of its external fuel tanks -- and launch a couple more strikes before heading home. In addition, the A-37A could be combat-turned in 90 minutes because of its high maintenance reliability. Its larger cousins would be still sitting on the ground. It was also common for the A-37 pilots to fly as many as five missions in a day, while the F-100 and F-4 pilot had only one mission.

According to From Trainer to Gunfighter: The A-37:During the twelve month deployment of the 604th not one of the units aircraft was lost to enemy action in the air although some did limp home with interesting holes in the wings and the odd engine trashed. The 604th logged its 10,000 combat sortie in May 1968 and had throughout the TET Offensive flown an average of 60 sorties a day with an overall availability rate of 87% throughout. Other role undertaken by the Squadron included many that they were primed for such as armed helo escort, CAS, CAP for ground convoys, FAC, armed recce and night interdiction. It was during the latter that pilots decided not to use the nose mounted minigun as the blast and tracers had a nasty habit of leading the enemy gunners straight back to the cockpit when retaliating. We end this look at the exploits of the 604th with a quotes from a couple of pilots. 1st Lt Charlie Carter" If we miss our target by 20 metres it is a disappointment, but the '37' is such a stable bomber that we can deliver our ordinance quickly and accurately." From Major Don Ellis" The missions we like are those where we can support troops in contact with the enemy, then we can see the results of our flying and know that we are directly helping out the troops". According to AFHRA: 14th FTW, the 604th ACS at Bien Hoa was detached from 14th SOW and attached to the 3rd TFW at Bien Hoa from 15 Nov 1967-1 Mar 1970. This was part of the master plan to "Vietnamize" the Vietnam War. According to Dave Blum in the Dec 2003 A-37 Association Newsletter, "As Nixonian Vitemanation took hold, two A37 Sqdns (8th and 90th) were Vietnamized, leaving the 604th and this became the 8th SOS at Bien Hoa."

604th Raps Building

(Bob Macaluso on A-37 Association)

The following is an article about the combat experiences of Ollie Maier in Daily University Star on 29 Oct 97. It stated, Flying back to the Vietnam WarOllie Maier tells about his hundreds of combat air missions as a war pilot

By Travis M. Whitehead

Senior Reporter

If Ollie Maier could rewrite the Vietnam War, he would make it more like the Gulf War. "A lot of good people died--Americans, Vietnamese and even North Vietnamese," said Maier, who served in Vietnam as a combat pilot from 1967 to 1968. "I wish we'd gone in the way they did in the Gulf War: get it over with and get out. We had our hands tied." Maier, who is now the energy conservation coordinator for the SWT Physical Plant, spent his tour of duty flying support missions for ground troops in South Vietnam. Based with the 604 Air Commando Squadron in Bien Hoa, a few miles north of Saigon, he flew 502 missions.

Ollie Maier points to a picture of a plane he flew in Vietnam. Maier flew more than 500 air missions while stationed in Bien Hoa, just north of Saigon.

Maier said this earned him the distinction of flying more combat missions in a one-year period than any other pilot in Vietnam as recorded in "A-37 Rap," a book published with a collection of stories from the pilots in 604 Air Commando Squadron. Maier said the A-37 was a trainer aircraft modified into a fighting aircraft. Because of this, it was considered a test unit, and he had the freedom to fly sometimes as many as five missions a day. Fighter pilots in other units were restricted to flying only one combat mission each day.

The aircraft soon proved its worth.

"We had an outstanding reputation for hitting targets," he said. "We were often called on because we knew how to get the job done."

Maier said the A-37 was not as fast as some aircraft and couldn't fly into North Vietnam. However, when support was needed for troops in the south, the A-37 was more accurate. Its advantage was that, because it could fly slower than other aircraft, it could fly lower to drop its load. The pilot could tell if the target had been hit and, if necessary, make multiple runs. Other, faster aircraft had to have higher altitude to pull up.

Maier said the only time he could see the people he was shooting at was when he was strafing. The hardest part, he said, was thinking about killing people.

"We all want to live," he said. "Regardless of what God we have, to take another's life is not that easy. But they were trying to kill me, and I was killing them in self-defense. You just more or less put it out of your mind."

Maier said he often didn't think he would survive.

"There were times I was scared I was going to die," he said. "I'd see friends get killed. I never actually saw them die, but they'd go on a mission and not come back, and I knew they were dead."

Maier said that out of 25 aircraft, the unit lost only five aircraft and seven pilots. Maier said he often returned with holes in his aircraft. Most of the time it didn't cause any trouble though.

The A-37, he said, was mechanically controlled, unlike newer aircraft which are powered by electronics and hydraulics. If you lose the hydraulics in the newer aircraft, he said, you lose complete control. The A-37 was much more accomodating to damage. "We had two engines," he said. "If one was shot out, you still had the one."

There were a few times when Maier said he ran into trouble.

"My bomb and fuel tank system was shot out," he said. "I tried to drop my bombs and I couldn't, so they told me to go over the ocean and push a button. That would clean the wings out. It only cleaned the left one out."

As a result of this, he had difficulty landing and a wheel blew out, forcing him off the runway.

"The procedure afterward, if that happened again, was to bail out," he said. "It was just too dangerous."

Maier said the only people who didn't like the A-37 were the enemy and the politicians. The A-37 was made by Cessna airplane manufactuers. Maier said Cessna didn't have as much clout as other airplane manufacturers, which later made the A-10 to replace the A-37.

"When you have politicians fighting a war instead of the military, it's going to be different," he said. "It's easy for politicians when they're physically detached. If they had their desks in the trenches with the men, it might be different."

Maier pointed out it was easy to second guess a situation without knowing all the information. "Maybe their thinking was, if it got overpowering, the Chinese Communists would've come in," he said.

"If it was up to me, I would've went in and showed my power."

The following is a "war story" written by Ollie Maier from the Sept 1991 Newsletter of the A-37 Association:Lloyd Langston was leading thsi one and I was on the wing. We had already been in Nam for several months and were pretty familiar with the areas, targets, etc.

We were working some target down in IV Corps when the FAC advised us another FAC had a higher priority target not too far away. Although we didn't have much of a bomb load left, we switched radio channels and flew to the rendezvous for the new FAC. There he briefed us onthe target.

"This is a target I've had my eye on for several months, " he said. "It is a building in the middle of a small city that Charlie has been using as a munitions plant. Not only is there munitions there, but one of the Charlie's fuel storage areas is also along side of it."

"I have finally just received permission from the district chief to hit it...and I want to do so before he changes his mind," he continued.

"Since it's the biggest building right in the center ofthe city, I'm not even going to mark it. I don't wnat to alert the enemy working in it." (And it was a big building. From the air it look like a one or two story building with a tin roof that covered almost a city block. It had a river by it and canals all around.)

"You don't have to worry about how close the friendlies are as the whole area is considered unfriendly," he added.

As mentioned before, we didn't have much of a bomb load left. I think Lloyd had a couple of small 250 pounders and I had a couple of cans of nape...plus our mini-guns.

Lloyd rolled in, put his pipper on the target, and let one of the 250s go. When it hit the target, it was the biggest explosion I had ever seen. The FAC, who was flying off to a side, said the fireball went to over 500 feet...and later the smoke went to above 4,000 feet.

This smoke was from all the burning barrels of fuel. What the initial explosion didn't set off, I probably was instrumental it helping set off with the cans of nape. I really can't say for sure as it seemed the whole area was burning as I made my bombing runs.

The burning fuel was not only in the immediate area but it had flowed into the surrounding canals or stacked alongside of them) setting them afire.

Even though the intial explosion truly showed what one little airplane and one little bomb accurately delivered can do, this point wasn't really driven home until later back at the base.

On the way back to base, probably about half way, we met a flight of eight F-4s operated in flights of two or four. They were headed in the direction we had just come from.

When we landed we were informed that as soon as Saigon learned that the munitions plant was on the target list, they set up a special flight just for it.

That was the flight of F-4s we saw. Since we had totally destroyed the target, they had to be diverted to some mundane target. I understand they and their ops people were really quite pissed that a couple of half loaded A-37s had stolen their glory. The 604th ACS had its share of combat casualties with the A-37, but much less than expected for a close air support unit engaged in some of the most dangerous flying situations. The 604th ACS had seven pilot losses. Two are as follows:- Major Ronald D. Bond: According to Task Force Omega, "On 11 March 1968, Major Ronald D. Bond was the pilot of an A37A Dragonfly that departed Bien Hoa Airbase on a close air support mission for ground troops engaged in a battle with Viet Cong (VC) forces some 47 miles to the southeast. After making a strafing run over the target located on a hillside surrounded by rice paddies, the aircraft was struck by hostile ground fire, crashed and exploded upon impact approximately 2 miles east of a primary road and 4 miles west of the coastline. The location of loss was approximately 10 miles northeast of the major coastal base of Vung Tau, 44 miles southeast of Saigon and just north of the town of Long Hai, Long Dat District, Phuoc Tuy Province, South Vietnam. ... Ronald Bond most certainly perished in the crash of his Dragonfly."

- 2Lt David Whitehill: Another incident according to the Virtual Wall happened on 24 May 1968. David Whitehill was flying an A-37 as escort to a C-123K "Ranch Hand" spray aircraft near Rang Rang, about 30 miles northeast of Bien Hoa. When the C-123 came under fire, Whitehill attacked the gun position. On his third pass he apparently was hit by ground fire - he failed to pull out and crashed near the gun site.

According to the AFHRA: 3rd Wing, it was assigned to the 3rd TFW from 1 March–30 Sep 1970. The unit was deactivated when the 8th SOS began operations at Bien Hoa.

Bien Hoa Attack (1965)

(USAF Photo)TET Offensive (Jan 1968) From the Gold Bar Magazine (www.ocsfoundation.com/magazine) article A Look Back in Time

Air Force's Ground Support in Vietnam by Sam McGowan on 14 May 2002: Bien Hoa was hit at 0300 on January 31 by 35 rounds of 122mm rocket fire and 10 rounds of 82mm mortar fire. Almost immediately, an Air Force sentry-dog handler reported that the base was being penetrated. An enemy force of eight companies breached the perimeter at four points from the east; a fifth penetration was halted by fire from Army gunships. A concrete pillbox directly in the path of the advancing force became the center of resistance as the Air Force security policemen inside maintained a heavy fire against the attackers, catching them in a crossfire. By 0400 the attack had been halted east of the flight line by security policemen and security augmentees supported by Army helicopter gunships.

By dawn the enemy was resisting at only three points: an aircraft engine test stand in a revetment near the runway, the aircraft de-arming pad, and near one of the penetration points on the eastern perimeter. A counterattack, followed by a final sweep of the field supported by Army gunships, terminated all enemy resistance by 1640. Air Force casualties were four killed and 26 wounded; two airplanes were destroyed by shelling and two were damaged. Enemy losses were 139 killed and 25 taken prisoner inside the base. Another 1,164 were killed and 98 captured in the immediate Bien Hoa area. According to History Net: Lt. Colonel Charles A. Beckwith: An Unforgettable Character by Bill Bell:Sometime around 3 a.m. on January 31, with the local guard force incapacitated, VC sappers--wearing only undershorts and with wire-cutters suspended around their necks on nylon laces--began to infiltrate the wire aprons of the minefield at the end of the runway, with the intention of blowing up the base's tactical aircraft. As the sappers probed for mines, a 101st Airborne soldier who was manning an M-60 machine gun saw something moving out there and began to fire. ...

The main thrust of the attack was blunted thanks to early discovery, and the enemy did not breach the perimeter, thanks to the engineers of the 326th. Because the sappers had been stopped, we were able to get the fighters based at Bien Hoa back in the air quickly once the brunt of the fighting was over. But VC and NVA troops continued to pour deadly automatic-weapons fire into the base from outside the perimeter throughout the first day of Tet. During the ensuing sweep around the perimeter, the firing was so pervasive that the commanding general's secretary was killed while typing at his desk. The vulnerable buildings outside the perimeter were hit hard by the VC and NVA, many of them completely destroyed.

When the attack petered out, the bodies of killed and wounded VC and NVA were scattered in the brush and tall grass around the perimeter. We determined that some of the VC had apparently been special action unit personnel, since inside their packs we found starched and pressed VNAF uniforms. Had they managed to get inside the air base and assume their disguises, they could have created considerable confusion between the American and South Vietnamese personnel, even after first light.

As it was, more then 500 VC were killed and 40 more captured in the Bien HoaLong Binh area. When the smoke cleared at the air base perimeter, 115 VC and NVA bodies were piled in the wire. The following day, the bodies were covered with lime and buried using a bulldozer in one common grave at the end of the runway.

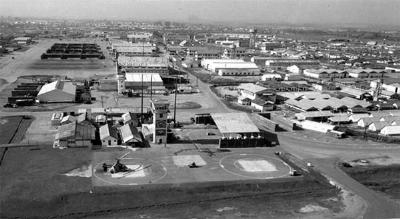

Aerial view of Bien Hoa

(John Lamb on A-37 Association site)

Aerial view of Bien Hoa

Bien Hoa from Runway 27L (looking south)

(Det 6 600th Photographic Squadron:

Wavelen Wayne Fielder)

Bien Hoa Tower with Pedro HH-43B in front

(Det 6 600th Photographic Squadron:

Wavelen Wayne Fielder)

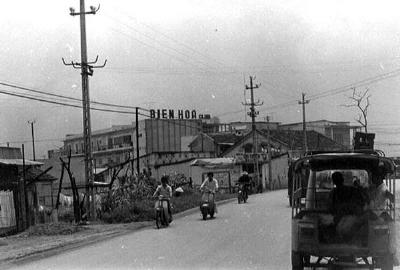

Outside Bien Hoa Main Gate

(Det 6 600th Photographic Squadron:

Wavelen Wayne Fielder)

90th Attack Squadron, 3rd TFW, Bien Hoa (1969-1970)

The 90th was with the 3rd TFW at Eglin when it transitioned to F-100s. The 90th was redesignated on 8 Jun 1964 as the 90th Tactical Fighter Squadron. When the 3rd was rotated to Vietnam, the 90th accompanied it. On 8 October 1966, the wing transferred to Phan Rang Air Base, Republic of Vietnam, replacing the 366th Wing. With the transfer, the 35th became the parent wing at Phan Rang Air Base and began operating F-100 aircraft with Detachment 1 of the 612th Tactical Fighter Squadron from Misawa, Japan. The 90th TFS (Dicemen) was first assigned the 3rd TFW at Bien Hoa AB on 3 Feb 1966 flying the F-100. In 1969, the 90th TFS started its transition to the A-37B while still assigned to the 3rd TFW. It was attached to the 3rd TFW from 3 Feb 1966–31 Oct 1970.

The 8th and 13th Tactical Bomb Squadrons flying their B-57s followed the 35th to Phan Rang Air Base, while the wing gained an attached organization: the Royal Australian Air Force Squadron No. 2, equipped with MK-20 Canberra bombers. In July 1969, the B-57s were phased out of the USAF inventory and the remaining B-57s sent to the boneyard. The 8th was transferred without equipment and personnel to the 3rd TFW in preparation for its transition to the A-37B. The 13th TBS was inactivated. In the meantime, the 90th was standing down as well in preparation

SITE NOTE: By 1965, the F-100s were experiencing severe shortages in Vietnam and all assets were drained from the ANG. The F-105 could carry a larger bombload further and faster. In addition, the F-105 was built to take the extreme structural loads of low-level, high-speed flight, whereas the F-100 was not. Consequently, from mid-1965 onward, F-100D fighter bombers generally operated only in the South, leaving the North for the F-4 and the F-105. In this role, the F-100 was only moderately effective as a ground attack aircraft because it lacked the maneuverability to operate in very close proximity to friendly troops under enemy attack. Then in 1967 a catastrophic wing failure was caused by a series of wing cracks that had been produced by metal fatigue. All F-100s were temporarily restricted to a 4-G maneuver limit until all the planes could be fixed by carrying out a complete modification of the wing structural box. These modifications were not completed until 1969. This limited the usage of the F-100s in its role as a strike aircraft. All of this added to the pressure to field more A-37B strike aircraft as soon as possible...and to convert units to this aircraft. After the success of the Combat Dragon program and the incorporation of its suggestions in the A-37B. The prototype of the B-model was first flown in September 1967 and deliveries began in May 1968. Once deliveries were made, the USAF started the pilot training for the cadre of two squadrons of A-37B aircraft -- the 90th and 8th. After completion of training, the A-37Bs were broken down and shipped to Bien Hoa via C-133s. The pilots departed England for the Philippines for Survival Training and when they arrived at Bien Hoa after completion of the training, the aircraft was awaiting them all assembled.

The 90th did the first combat acceptance of the A-37B in Vietnam when they started to arrive around Sept 1969. The unit was combat certified on December 1969. Immediately, the unit was redesignated as the 90th Attack Squadron on 12 Dec 1969.

The 90th had been continuously associated with the 3rd Wing since 1919. But this long association came to an end when the 3rd TFW became a "paper wing." The assets of the 90th Attack Squadron, along with the 8th Attack Squadron, were turned over to the RVN Air Force as part of Nixon's "Vietnamization Program."

The close out of operations for the 90th at Bien Hoa also marked the end of the 3rd TFW in Vietnam. During May and June 1970, the 3rd TFW participated in the Sanctuary Counteroffensive in Cambodia aimed at depriving the enemy the use of its sanctuary bases and destroying its leadership. The campaign marked the 3rd TFW's last major operation. On 31 October 1970, the 3rd Tactical Fighter Wing ended its duties in Vietnam. Unmanned and unequipped, the wing remained active in a "paper" status until it moved in name only to take over Kunsan AB, Korea.

According to AFHRA: 90th FS, on 31 Oct 1970, the 90th Attack Squadron was redesignated the 90th Special Operations Squadron and moved to the 14th Special Operations Wing at Nha Trang where it switched to C-123K Ranch Hand and AC-130 aircraft.

8th Attack Squadron, 3rd TFW, Bien Hoa (1969): By July of 1969, the 8th Tactical Bomb Squadron's strength was down to only 9 aircraft. By the end of July, the squadron was down to 8 and it was decided that it was time to retire the B-57B from active service. The surviving aircraft were sent back to the USA in September and October and put into storage at Davis-Monthan AFB, AZ.

At the same time the decision was made to convert the 8th TBS into a A-37B unit. The elimination of the B-57 also presented a problem with the need for a replacement for the aging A-1E Skyraiders and the decommissioned B-57Bs as strike aircraft. The answer appeared to be the A-37B to fill the niche for a "counter-insurgency" (COIN) aircraft.

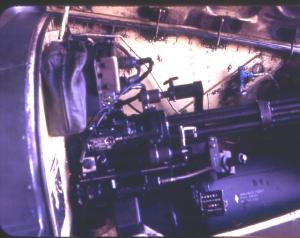

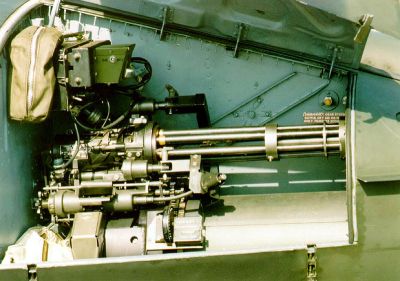

The A-37B aircraft, like the A-model, had a 7.62 Gattling Minigun in the nose, gun cameras, and armor protection for the pilots. It also had self-sealing fuel tanks, a tracking beacon system, and the ability to directionally track VHF and UHF signals. The prototype of the B-model was first flown in September 1967 and deliveries from the factory began in May 1968.

SITE NOTE: Plans for both the 8th and 90th squadrons to be attached to the 3rd TFW seems to have been driven by a historical imperative. The 8th and 90th had a long history as sister squadrons in the 3rd Bomb Group dating back to WWII and Korea. Later this same historical imperative, preserved the 8th SOS from deactivation as it was one of the oldest continuously active squadrons in the USAF.

In addition, there was a lot of pressure on fielding the A-37B as a counter-insurgency (COIN) aircraft to replace the aging A1-Es and mechanical problems of the F-100s. The A-37B was one of the few aircraft to be able to carry its own weight in munitions. This meant a combat configuration of 4 Mk82 500 lb bombs, 2 pods of rockets, and a load of gun ammo. This was equivalent to the load carried by the F-100 Super Saber (not counting the 20MM gun). In close range missions, the A-37 could actually get bombs on target faster than the F-100 since the "Hun" had to burn off some fuel before it could go to work. It could also hit the target, climb up to pattern altitude and return to make another pass quicker than any other fighter. It could quick-turn in 90 minutes and its survivability surprised even the most hardened skeptics. It would have been logical to assume that because of the performance of the A-37B in its strike role that more units would have been fielded other than the 8th, 90th and 604th.

At the same time, one must realize that the Nixon "Vietnamization Program" was being stressed as the U.S. wanted to desparately extract itself from the quagmire of the conflict. Thus rather than field more USAF squadrons, the military pursued turning the A-37Bs over to the RVNAF. Of the 577 A-37s built, only a handful saw combat with the USAF.

The 4532nd Combat Crew Training Squadron at England Air Force Base in Louisiana initially trained over 100 South Vietnamese Air Force pilots. Each VNAF student received 112 hours of ground instruction and 85 hours of flight training. After training was completed, the VNAF pilots returned to Vietnam to fly A-37's supplied under the US Military Assistance Program (MAP). South Vietnam had 10 squadrons of A-37's at peak strength during the early 1970's. In Jul 1969, the 8th Tactical Bombardment Squadron officially phased out its B-57s in the 35th TFW. The last B-57B was sent stateside in Oct 69. The 8th TBS designation moved to Bien Hoa AB, South Vietnam on 15 Nov 1969 without personnel or equipment and was attached to the 3rd TFW.

NOTE: There seems to be some confusion on the ACTUAL movement dates to Bien Hoa. According to Air war College: 25th ID After Action Report, during the 4-day battle of at Renegade Woods on 2 April, 1970, the 8th Attack Squadron of 35th TFW Phan Rang supported the effort with 2 A-37s carrying "4 500 lbd HE; 4 500 lbd napalm." At this time we believe this is a historical error. This would indicate that the 8th Attack Squadron was STILL at Phan Rang in April 1970. It is possible that the report had mistakenly identified the 8th Attack Squadron, 3rd TFW, Bien Hoa (A-37s) for the 8th Tactical Bomb Squadron, 35th TFW, Phan Rang (B-57s) which departed Vietnam in Oct 69. With the delivery of the new A-37Bs to the USAF, the cadre of pilots started training at England AFB in Louisiana on the A-37s for both the 8th Attack Squadron and 90th Attack Squadron. In 1969, the initial cadre of pilots for the 8th Attack Squadron's A-37Bs were trained at the 4532nd Combat Crew Training Squadron (CCTS) at England AFB -- along with the pilots for the 90th Attack Squadron. The 4532CCTS/4410th SOTG trained A-37 pilots for both the USAF and RVNAF. After the training was complete on the A-37B, the A-37B aircraft were broken down and shipped to Vietnam on C-133s, while the pilots were sent to Survival Training at Clark AB, Philippines.

According to Don McPhail of the 8th Attack Squadron in an email to A-37 Association site: Ollie Maier, "In 1969 two new A-37 squadrons were formed at England AFB. The squadrons trained in A37B's and when finished with the training the planes were taken apart and shipped to Vietnam on C-133's. The pilots left the base at the same time on C-141's enroute to Hickam and Clark AFB in the Philippines for jungle survival. By the time we got to Vietnam our airplanes were put together and ready for us."

"The two squadrons were the "8th Attack Liberty Sq" -- the "Dogs" and the "90th Attack Sq" -- the "Dice." The "604th -- Raps" were already there and kept their "A" models. The "8th" & "90th" squadrons only lasted in Vietnam for 10 months and the decision was made the give our airplanes to the RVN. Higher-ups wanted to keep the "8th" alive as the squadron had a very long history before we inherited the name in Vietnam but the "Raps" were the ones who were going to survive so the surviving squadron was the "8th" with the "Rap" call sign. The A-37B aircraft arrived first around Sep 69 and the pilots arrived around Oct 69 after completing survival training in the Philippines. The 8th Tactical Bomb Squadron was assigned to the 3rd Tactical Fighter Wing on 15 Nov 1969. It was redesignated the 8th Attack Squadron on 15 Nov 69 and started flying the A-37B three days later on 18 Nov 89.

The 90th Tactical Fighter Squadron was redesignated the 90th Attack Squadron on 12 Dec 69 but had already started flying A-37s in November along with the 8th. Both units were combat certified on 12 Dec 69. The 8th was combat certified on December 1969.

At this point, there were three squadrons of A-37s at Bien Hoa: the 604th "Rap", 90th "Dice" and 8th "Dog". The tail codes and radio call signs were 8th/3rd TFW "CF" (Dog) and 90th/3rd TFW: "CG" (Dice). Unfortunately, the "Dog" radio call sign for the 8th never seemed to catch on. The 604th ACS used "CK" (Rap). The 604th ACS/14th SOW was attached to the 3rd TFW at Bien Hoa. (NOTE: The 14th SOW was at Phan Rang.)

| 8th Attack Squadron | 3rd TFW | (Dog) | A-37B | Bien Hoa | Tail Code: CF | | 90th Attack Squadron | 3rd TFW | (Dice) | A-37B | Bien Hoa | Tail Code: CG | | 604th Air Commando Squadron | 14th SOW | (Rap) | A-37A/B | Bien Hoa | Tail Code: CK |

A-37B Arrival at Bien Hoa (1969)

(Bob Mead on A-37 Association)

A-37B Arrival at Bien Hoa (1969)

(Bob Mead on A-37 Association)8th and 90th Attack Squadrons Start Shutting Down (Mar 1970) The decision was made in 1970 to turn the A-37s of the 8th and 90th over to the Vietnamese Air Force under Nixon's "Vietnamization Program." Preparations were made for the transfer of aircraft to the RVNAF -- and USAF personnel to the 604th or reassignment.

At the same time, the decision was made to close out the 604th ACS while retaining the 8th Attack Squadron designation because of the significance of its being one of the squadrons with the longest record of continuous service dating back to WWI. This is the reason the 8th SOS retained the "Raps" call sign of the 604th ACS...instead of the "Dog" call sign that never caught on. The 604th ACS absorbed the personnel from the 8th and 90th Attack Squadrons which were closing out -- and then it was redesignated as the 8th Special Operations Squadron.

SITE NOTE: There seems to be some confusion as to which unit provided the cadre for the 8th SOS. The 8th Special Operations Squadron history (dated 6 Oct 93) states the 310th Attack Squadron at Bien Hoa was absorbed and redesignated as the 8th Attack Squadron. This is in error because of eye-witness statements from personnel stating the cadre came from 90th and 604th personnel -- and equipment from the 604th. According to AFHRA: 3rd Wing shows the 310th & 311th Attack Squadron was attached to the 3rd TFW only between15–30 Nov 1969. At this time, we are not certain where the 310th and 311th came from.

(AFHRA: 310th Fighter Squadron shows that the unit never bore the designation "Attack Squadron" and was reactivated as the 310th TFTS in Dec 1969. AFHRA: 310th Airlift Squadron shows the 310th Special Operations Squadron on 1 Aug 1968-1 Jan 1970 at Phan Rang, but this was a transport unit that never flew the A-37B.)

Wavelen Fielder and Michael Palmer

installing Gun Camera Film on 8th SOS A-37 (1970)

(Det 6 600th Photographic Squadron:

Wavelen Wayne Fielder)8th SOS, 35th TFW (Sep 1970) In Mar 1970, the 604th ACS was transferred from the 14th SOW at Phan Rang to the 35th TFW at Bien Hoa -- even though it had been attached to the 3rd TFW at Bien Hoa since its inception. At the same time in March 1970, the 90th Attack Squadron "Dice" and the 8th Attack Squadron "Dog" of the 3rd TFW started to close out operations with the A-37 aircraft and turned over their assets to the Vietnamese Air Force. The 90th SOS was assigned to the 14th SOW at Phan Rang on 31 Oct 70 where it converted to C123K Ranch Hands and AC-130 aircraft.

The 8th Attack Squadron transferred its personnel to the 604th ACS. As part of the transfer process, the 604th ACS transferred to the 3rd TFW on 1 Mar 70 and simultaneously changed its designation to the 604th Special Operations Squadron.

A-37B Flyby at Bien Hoa (1970)

(Bob Mead on A-37 Association site)According to A-37 Association site, "Bob (Mead) caught this unique image during a flyover at Bien Hoa in September or October of 1970. This could be the closing out of the 90th Squadron "Dice" or the 604th "Raps." The Raps and the Dice converged to become the 8th Attack Squadron and we didn't know if we were supposed to be "Daps" or "Rice" from that point on." Bob Mead was at Bien Hoa from 1969-1970.

Later Don McPhail wrote to A-37 Association site, "My comments referred to a picture already on the web site. The picture is the first picture with the title "A-37's in diamond formation" by Bob Mead. That's all under the caption of Bien Hoa Diary #4 by Bob Mead. The caption under the picture has the facts a little confused and I was trying to straighten things out a bit. ... Once again, the picture of 16 A-37's in four diamonds in trail was taken over Bien Hoa and consisted of Dogs and Dice on their last flight. The flight was led by Col. Tomlinson who was the Dog squadron commander and I was his slot man. ..."

In other words, Don McPhail was commenting on the 8th and 90th flying together for the last time -- not the 90th and 604th. The 90th was to be transferred to the 14th SOW and transitioned into the C-123K. The 90th assets were turned over to the Vietnamese and the 604th was disbanded. The assets and personnel became the 8th SOS cadre. |

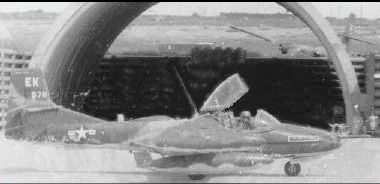

The 604th SOS closed the doors on its operations at Bien Hoa on 30 Sep 1970. Simultaneously on 30 Sept 70, the 8th Attack Squadron was redesignated as the 8th Special Operations Squadron and transferred to the 35th TFW -- as the 3rd TFW was being inactivated. The 8th assumed the tail code "EK" on 30 Sep 70.

In effect, the 604th ACS became the 8th SOS. The official 8th SOS call sign "Dog" never caught on and the pilots continued to use the "Rap" call sign. The "Rap" was already a recognized call sign for A-37 strike aircraft -- and, as many of the men came from the 604th, there would be a natural reluctance to change their old call sign. The 8th SOS assumed not only the men and equipment from the 604th SOS, but it also assumed its nickname, the "RAPS."

Ollie Maier of the 604th ACS wrote, "As I understand it, the call sign RAPS (Dragons was already used by a Vietnamese unit) came from our first commander, Col Weber. He had a close friend whose initials were R.A.P. and he wanted to acknowledge the help he

had given... thus RAPs."

However, the new squadron did take on a new tail code of "EK" for the 8th SOS. SITE NOTE: There are confusing references to the tail code "EK." According to From Trainer to Gunfighter: The A-37, the A-37B aircraft were assigned to the "8th SOS/3rd TFW[CK], the 14th SOW [EK] and the 315th SOW at Phan Rang." (SEE CONFUSION: Tail code: "EK" for the 8th SOS/14th SOW for details.) The "EK" tail code at Bien Hoa was used by A-37s at Bien Hoa. There is a photo at VSPA: Photos showing an A-37 taxiing with the EK tail code.

A-37B EK Tail Designator at Bien Hoa (1970) (Raymond Morgan)| The photo was taken by Security Policeman Raymond Morgan (1969-1970) who was yelling and waving to attract the pilot's attention of an impending crash of a C-7 Caribou skidding towards the arch seen in the background. The C-7 made an wheels-up landing on a foamed runway because a shot up olio strut which wouldn't allow the left gear to come down. The C-7 stopped short of the arch. Morgan wrote on the USAF C-7 Caribou site: "The following story and photos were provided by Raymond Morgan who was based at Bien Hoa Airbase in 1969/1970. I was on duty with the 3rd Security Police at Bien Hoa Air Base at the time of the C-7 crash. I had drove over to the HOT Cargo area to see my brother Ssgt. Wayne Morgan when an in-flight emergency came over the radio. We were in a good spot to watch the C-7 coming in on final approach. The foaming truck had just finished when the C-7 touched down on the runway with wheels up. The pilot made a good landing but after the C-7 got about half way down the runway the left wing tip made contact with the ground and caused the C-7 to side to the left. The C-7 never made contact with the hanger but from were we were standing it sure looked like it was going to. An A-37 aircraft taxing by some hangers oblivious to the emergency. If you look through the hanger just above the pilot's head you can see a crashing C-7 Caribou about to slam into the hanger! The pilot was looking at us and we were yelling and waving frantically at him. He never knew what the hell we were shouting about. No body was hurt. Just another day at Bien Hoa." |

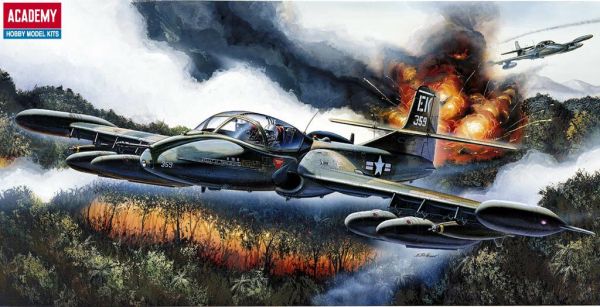

Static Display A-37B with EK Tail DesignatorCONFUSION: Tail code: "EK" for the 8th SOS/14th SOW??? There is a lot of confusion due to many web references that state the 8th SOS belonged to the 14th SOW. The references at Air Commandos and Gunships: Vietnam Era Tail Codes indicate that there was an 8th SOS/14th SOW with the "EK" tail code at Bien Hoa. Even popular models show the "8th SOS/14th SOW." For example, Academy Hobby Models has a model of an A-37B SuperTweet (#96359/EK, 8th SOS, 14th SOW, USAF, Bien Hoa AB, Vietnam, 1970).

Though it would be logical to state that a Special Operations Squadron would be assigned to a Special Operations Wing, the A-37Bs did not operate that way. The Vietnamization program was in full swing in 1970 when the "EK" code came into being. Only a handful of the 557 A-37Bs built were actually flown by the USAF in combat. The 90th SOS A-37Bs were turned over to the Vietnamese in 1970. The Vietnamese had 10 squadrons of A-37s. (NOTE: There are indications that A-37s flew missions from other bases for short periods of time to support local operations, but they were never attached to these wings.)

However, the primary reason we discount these references to an "8th SOS/14th SOW" is because AFHRA: 8th SOS and AFHRA: 14th Flying Training Wing show that the 8th was NEVER attached to the 14th SOW. (SITE NOTE: The 90th SOS converted out of the A-37B and joined the 14th SOW (1970-1971) flying C-123K and C-130 aircraft.)

The following is an example of the confusing "8th SOS/14th SOW" reference. According to Aircommandos: Air Commando and Special Operations aircraft used at major bases during the Vietnam War:

| Base | Unit | Aircraft | Call Sign Tail Code | | Bien Hoa | 8 AS/3 TFW | A-37B | CF | | Bien Hoa | 90 AS/14 SOW | A-37B | CG | | Bien Hoa | 604 SOS/3 TFW | A-37A/B | CK | | Bien Hoa | 8 SOS/14 SOW | A-37B | EK | | Bien Hoa | FS©/3 TFW | F-5A | None-transferred its 18 aircraft

to 522nd FS,

VNAF, 17 Apr 1967 | | Bien Hoa | 12 ACS/315 ACW | UC-123B/K | Ranch Hand | |

Again we repeat, records indicate that the 8th was NEVER assigned or attached to the 14th SOW.

Another reference that has caused confusion are the call signs for the A-37s listed in the 619th TCS Training Manual (Orientation Manual about 1969-70) at 505th Tactical Control Group. In it there is a reference to "2. Hawk A-37 Bien Hoa" in addition to the 8th, 90th and 604th. There was fourth A-37 unit at Bien Hoa. In addition, the "Hawk" was a call sign assigned to the F-100s at Bien Hoa. As the Orientation Manual was written in 1969-70, we believe this "Hawk" reference was in preparation for the 8th AS, 3rd TFW converting to the 8th SOS, 35th TFW.

To add to the confusion, according to From Trainer to Gunfighter: The A-37 stated "In Vietnam the A-37B equipped the 8th SOS/3rd TFW [CK],the 14th SOW [EK] and the 315th SOW at Phan Rang." Though the book is a highly authoritative source, we opt to disregard portions of this passage. In addition, the following errors appear on many hobbyist websites of vets documenting their personal experiences at Bien Hoa, Vietnam.

The first reference to the 8th SOS/3rd TFW (CK) is correct, but the 14th SOW (EK) reference we believe is in error. We believe that the "EK" tail code NEVER was associated with the 14th SOW. At Bien Hoa only the 604th ACS was attached to the 14th SOW, but they had the "CK" tail code.

Then we have the constant mention of the 8th SOS belonging to the 315th SOW. According to the AFHRA: 315th Airlift Wing, the 315th SOW was at Phan Rang from 68-70, but it did NOT fly the A-37. It flew the C-123K and AC-130. However, the 315th TAW at Phan Rang from 71-72 did fly the A-37 between 71-72. This is the 8th SOS. According to AFHRA: 8th SOS the 8th SOS was attached to the 315th Tactical Airlift Wing from 31 Jul 1971-15 Jan 1972. These muddled references cause us great confusion.

(NOTE: AFHRA: 315th Airlift Wing states that the 315th Air Commando Wing (1 Aug 67-1 Aug 68), then became the 315th Special Operations Wing (1 Aug 68-1 Jan 70), then the 315th Tactical Airlift Wing (1 Jan 70 - Inactivated 31 Mar 72). This shows the 8th SOS was assigned to the 315th TAW...NOT the 315th SOW.)

8th SOS Patch (1971)

(Richard Dutcher on A-37 Association site)8th SOS Starts to Pack Up to Go Home (1971) According to Historical Text Archives: Don Marby, "As US troops were being withdrawn, Nixon stepped up the use of US air and naval power. From 1969 to the end of 1971, the US had dropped 3.3 million tons of bombs on South Vietnam, North Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, more than Johnson had dropped in five years and more than the US had dropped on Europe and the Pacific in World War II. Nixon was trying to bomb the enemy into submission but it did not work. In the Spring of 1972, North Vietnamese forces launched an offensive which pushed back South Vietnamese forces. Nixon widened the bombing of North Vietnam and mined its harbors but the war was lost. The Nixon administration had been engaging in secret negotiations between 1969 and 1971 as Henry Kissinger made thirteen trips to France to meet with North Vietnamese diplomats. The US proposed a cease fire in advance of any political settlement and the preservation of the Thieu regime. Nixon had asserted that Thieu was one of the four or five greatest political leaders of the world, and supported Thieu in the 1971 presidential election, one so fraudulent that all of his opponents withdrew. But in 1972, shortly before the US presidential election, Nixon announced progress towards a cease fire. The war ended in 1973. Nixon resigned in 1974 so he did not preside over the rout of the South Vietnamese in 1975 when the North Vietnamese armies took over the entire country."

The Nixon "Vietnamization Program" was officially announced on Nov. 12, 1971 when Nixon stated that U.S. ground forces were in defensive role. Offensive actions would be handled by South Vietnamese. This policy came about because Nixon could not muster any support for the Vietnam War -- even amongst his closest advisors. The U.S. wanted out of the quagmire of Vietnam.

The turning over of the aircraft to the Vietnamese was part of the Vietnamization policy. The so-called Nixon Doctrine stated that the U.S. would provide military aid to Asian countries under Communist assault -- including air and naval forces if required -- but would under no circumstances involve US ground forces. Thus the idea was to transfer the equipment to the Vietnamese so that they could fight the battles themselves. Unfortunately, there was a fatal flaw in Vietnamization. South Vietnamese forces were trained in the American style of war in which, whenever possible, US planners would use overwhelming airpower to destroy enemy resistance before sending in US ground forces for battle. The VNAF was too small to provide such air support for bombing, troop mobilization and resupply. It was doomed from the start. The grunts in the field knew Vietnamization was a farce -- but they all wanted to go home as well.

The following is article by Dave Blum in the Dec 2003 newsletter of the A-37 Organization:

As Nixonian Vietnamation took hold, two A-37 Sqdns (8th and 90th) were Vietnamized, leaving the 604th and this became the 8th SOS at Bien Hoa.

The 3rd TFW F-100s and those from Tuy Hoa, Phu Cat, etc were sent home. Thus when at the 7AF/DO fighter mission frag mission, it became clarion clear that while we were declaring victory and turning over these CAS/interdiction assets to the VNAF, the NoViets were still coming and now with armor and mech stuff. (Or more to do today with less than yesterday.)

The A-37 and the AC-130s became the CAS system of choice and each continued to provide the accuracy and reliability that before was shuffled off or discounted because of their non-traditional n0on-signle seat single engine bearing.

How many times did the bosses turn and ask "How many sorties can the 8th generate", after his direction for 16 F-100 sorties was refused because the huns had gone home...and the F-4s were committed to Route Pack, etc.

We A-37s went abruptly from pre-Vietnamization Blow Job missions (Blow the Nipa Palm this today and that way tomorrow, No BDA) to an almost complete and continuous Alert Pad launch of the 8th SOS A-37s. Here we found ourself busy.

This started with the AF/Army Aviation joint exploitation of the bunker complexes and troop staging areas along the Cambode/Viet border (Parrot Beak - Fish Hook)

This, by the way, was the Bien Hoa A-37 CAS and Rustic FAC with Army Helio scout and attack copter integrated ops. Worked smooth and got fantastic results. We were tasked to strike not only massed NoViet truck parks but as well convoys.

Added to this was authorization to go after the big barge and riverboat traffic on the big rivers. Here we needed a far bigger gun.

Joke of the day was: How many rounds of 7.62 minigun does it take to sink a pirouge? Ans: Enough to over load it so it'll sink. (Or no explosive rounds, no holes in the wood boats...)

Buggers would run the small cargo boats under the tree canopy along the river banks. So we'd get down to the surface and at almost point blank strafe the nothers, learned some good uses for the slot lip spoilers for slow speed strafe roll control...Flaps down a bit, screens up and blast away...(gun sight is not needed here).

The only way to get a secondary or fire was to cause the 7..62 bullets to spark that might ignite fuel or driy packing material.

Oh for sure we used the Napes, and CBU's as well, but these were not that useful when going after little barges and pirouges along the river banks... Sadly, too few A-37s, and too late the evidence of worth to have a decided impact.

Up in the DaNang area there was insuffient light CAS, so the prohibition placed on OV-10 CAS before was overcome by events. (Seems the fighter jocks in command did not want FAC's doing CAS even if the target was fleeting and weapon capability could be effective.)

However, when things were on the downslide up there, the OV-10s were allowed to hang drop and fire ordnance on the stubs and allowed to shoot their M-60's at real bad guys.

The OV-10 was designed for multi-role missions from paradrop to CAS, but were not allowed in AF to do more than FACing until it became necessary...making it worse was that the Marines were and had been using their OV-10s in all roles and missions ... same plane, different rules....

Silly and stupid... Richard Dutcher, MSgt, USAF (Ret) wrote on the A-37 Association, "I was assigned to the 8th SOS as an A1C from 12 Dec 71 to 14 Nov 72 -- when the aircraft were finally turned-over to the VNAF and the pilots were sent home and the squadron returned to stateside. The First Sergeant at that time was MSgt Stevic (home somewhere around Minot, ND). The Admin Officer was Capt Brumbelow (home in Alabama?). The Commanders: Col Ledbetter ( ??? - May 72). Col Weed (May 72 - Nov 72)." He attached some interesting photos of the time including the squadron patch.

A-37B Over Vietnam (1971)

(Richard Dutcher on A-37 Association site)

A-37B Over Vietnam (1971)

(Richard Dutcher on A-37 Association site)

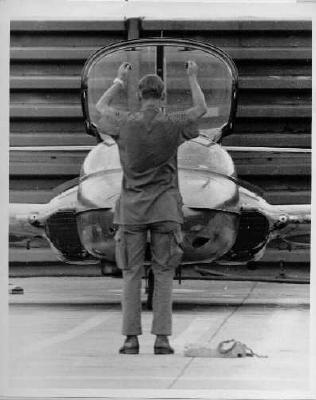

A-37 Crewchief (1971)

(Richard Dutcher on A-37 Association site)

Air Force Advisory Team #6 had a bar.

Seated (L to R) are

MSgt Warren Hammaker (Intel NCO), TSgt Dan Brannan (Life Support),

A1C Rick Dutcher (Admin).

(Richard Dutcher on A-37 Association site)

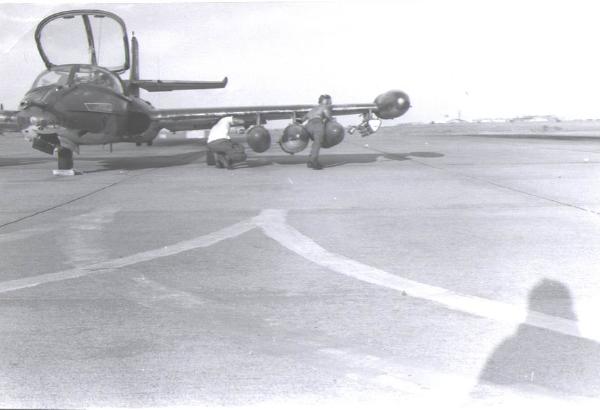

Photos Courtesy William R. Stevens, MSgt, USAF (Ret)

Line Chief/"B"

Flight Chief, 8th SOS (Dec 71-Nov 72)

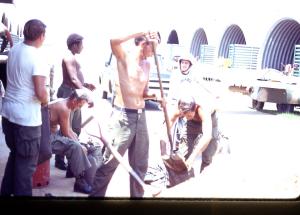

1. 72-3-17, Acft 355 #4 crashed at end of runway; 2. 72-03, 4 A-37's at OER; 1. 72-3-17, Acft 355 #4 crashed at end of runway; 2. 72-03, 4 A-37's at OER;   3. 72-03, A-37 at EOR; 4. 72-03, Behind barrier, walkway at barracks; 3. 72-03, A-37 at EOR; 4. 72-03, Behind barrier, walkway at barracks;   5. 72-03, Msgt Stevens & brother Danny (Army); 6. 72-03, Danny Stevens, brother visiting me at Bien Hoa #2; 5. 72-03, Msgt Stevens & brother Danny (Army); 6. 72-03, Danny Stevens, brother visiting me at Bien Hoa #2;    7. 72-03, EOR to country side; 8. RAPS sign at ops building; 9. 72-03, RAPS sign on revetment wall; 7. 72-03, EOR to country side; 8. RAPS sign at ops building; 9. 72-03, RAPS sign on revetment wall;   10. 72-03, Recip engine shop ''Robot'; 11. Brother Danny observing Msgt Stevens doing run on 347; 10. 72-03, Recip engine shop ''Robot'; 11. Brother Danny observing Msgt Stevens doing run on 347;   12. Both Stevens boys sitting on bombs; 13. 72-04, A-37 gatling gun bay; 12. Both Stevens boys sitting on bombs; 13. 72-04, A-37 gatling gun bay;   14. 72-5-2, Crashed & burned on base - Lt Moorehead OK; 15. 72-5-2, 'DEROS' on top of new bunker 'Guard Duty'; 14. 72-5-2, Crashed & burned on base - Lt Moorehead OK; 15. 72-5-2, 'DEROS' on top of new bunker 'Guard Duty';    18. 72-6-12, Acft 360, still cleaning dockpit rt side of camopy gone; 19. 72-6-12, Acft 360, bullet entered thru rt side of speed brake; 20. 72-6-12, Acft 360 #4, still cleaning & repairing; 18. 72-6-12, Acft 360, still cleaning dockpit rt side of camopy gone; 19. 72-6-12, Acft 360, bullet entered thru rt side of speed brake; 20. 72-6-12, Acft 360 #4, still cleaning & repairing;    21. 72-6-12, Acft 360 #5, still cleaning & repairing; 22. 72-6-12, Acft 360 #6, bullet hole left wing near jack pad; 23. Acft 360 #7, bullet hole in flap recess; 21. 72-6-12, Acft 360 #5, still cleaning & repairing; 22. 72-6-12, Acft 360 #6, bullet hole left wing near jack pad; 23. Acft 360 #7, bullet hole in flap recess;   24. 72-06, 358 almost repaired; 25. 72-06, A-37 right wing loaded with a variety or ordinance; 24. 72-06, 358 almost repaired; 25. 72-06, A-37 right wing loaded with a variety or ordinance;   26. 72-06, 750's waiting to be loaded; 27. 72-06, A-37 right wing with 750 pounder; 26. 72-06, 750's waiting to be loaded; 27. 72-06, A-37 right wing with 750 pounder;   28. 72-06, Broke nose strut off on take off 69-6340; 29. 72-06, Broke nose strut off on take off 69-6340 #3; 28. 72-06, Broke nose strut off on take off 69-6340; 29. 72-06, Broke nose strut off on take off 69-6340 #3;   30. 72-06, Broke nose strut off on take off 69-6340; 31. 72-06, A-37 taxing in storm creating wake; 30. 72-06, Broke nose strut off on take off 69-6340; 31. 72-06, A-37 taxing in storm creating wake;   32. 72-06, Contraption; 33. 72-06, Last flight in revetment; 32. 72-06, Contraption; 33. 72-06, Last flight in revetment;   34. 72-06, Col Weed fini flight; 35. 72-06, Col Weed; 34. 72-06, Col Weed fini flight; 35. 72-06, Col Weed;   36. 72-06, Crew chief signaling pilot; 37. 72-06, Crew chief fishing in puddle after storm; 36. 72-06, Crew chief signaling pilot; 37. 72-06, Crew chief fishing in puddle after storm;   38. 72-06, Lt Col Weed taken to last flight; 40.72-06, Msgt Stevens & Sgt Gilsdorf working on 340; 38. 72-06, Lt Col Weed taken to last flight; 40.72-06, Msgt Stevens & Sgt Gilsdorf working on 340;   41. 72-06, Rap Mobile with smoke; 42. 72-06, Rocket damage to asphalt; 41. 72-06, Rap Mobile with smoke; 42. 72-06, Rocket damage to asphalt;   43. 72-06, The hose down begins; 44. 72-06, The hose down begins; 43. 72-06, The hose down begins; 44. 72-06, The hose down begins;   45. 72-07, After the work was done; 46. 72-06, took a .51 in the refueling boom; 45. 72-07, After the work was done; 46. 72-06, took a .51 in the refueling boom;   47. 72-07, Col Ledbetter's fini - with Msgt Stevens & Sgt Wynn; 48. Col Ledbetter's fini - with champagne; 47. 72-07, Col Ledbetter's fini - with Msgt Stevens & Sgt Wynn; 48. Col Ledbetter's fini - with champagne;   49. 72-07, Col Ledbetter's fini - with Col Weed; 50. 72-07, Gattling gun; 49. 72-07, Col Ledbetter's fini - with Col Weed; 50. 72-07, Gattling gun;    51. 72-07, Guard house on perimiter rd; 52. 72-07, Msgt Stevens in status truck; 53. 72-07, On perimiter rd; 51. 72-07, Guard house on perimiter rd; 52. 72-07, Msgt Stevens in status truck; 53. 72-07, On perimiter rd;   54. 72-06, We have to tow with anything; 55. 72-07, Ramp & taxiway near revetment work; 54. 72-06, We have to tow with anything; 55. 72-07, Ramp & taxiway near revetment work;   56. 72-07, Ramp & taxiway near transient area; 57. 72-07, Sgt Siple, Msgt Stevens with 343; 56. 72-07, Ramp & taxiway near transient area; 57. 72-07, Sgt Siple, Msgt Stevens with 343;   58. 72-08-31, mortar scar; 59. 72-08-31, revetment with remains of 339; 58. 72-08-31, mortar scar; 59. 72-08-31, revetment with remains of 339;   60. 72-08-31, inside revetment; 61. 72-08-31, inside revetment with pieces of 339; 60. 72-08-31, inside revetment; 61. 72-08-31, inside revetment with pieces of 339;   62. 72-08-31, same wall, but closer; 63. 72-08-31, looking toward front of revetment; 62. 72-08-31, same wall, but closer; 63. 72-08-31, looking toward front of revetment;   64. 72-08-31, another view of back side wall; 65. 72-08-31, view of top damage same revetment; 64. 72-08-31, another view of back side wall; 65. 72-08-31, view of top damage same revetment;   66. 72-08-31, mortar scar on taxiway between revetments; 67. 72-08-31, view of wall that was moved by blast; 66. 72-08-31, mortar scar on taxiway between revetments; 67. 72-08-31, view of wall that was moved by blast;   70. 72-08-31, damaged wing & tank acft 358; 71. 72-08-31, freedom bird taxiing by damaged area; 70. 72-08-31, damaged wing & tank acft 358; 71. 72-08-31, freedom bird taxiing by damaged area;   72. 72-08-31, damaged ambulance; 73. 72-08-31, damaged revetment - from alert pad; 72. 72-08-31, damaged ambulance; 73. 72-08-31, damaged revetment - from alert pad;   74. 72-08-31, Ssgt Rusk, Msgt Stevens, Sgt Treese where 339 sat; 75. 72-08-31, 339 blew up in this revetment - blast deflector; 74. 72-08-31, Ssgt Rusk, Msgt Stevens, Sgt Treese where 339 sat; 75. 72-08-31, 339 blew up in this revetment - blast deflector;   76. 72-08-31, 339 blew up in this revetment - from outside #1; 77. 72-08-31, 339 blew up in this revetment; 76. 72-08-31, 339 blew up in this revetment - from outside #1; 77. 72-08-31, 339 blew up in this revetment;   78. 72-08, Remaining ordinance destroyed (OED) #2; 79. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 78. 72-08, Remaining ordinance destroyed (OED) #2; 79. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions;   80. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 81. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 80. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 81. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions;   82. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 83. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 82. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 83. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions;   84. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 85. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 84. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 85. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions;   86. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 87. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 86. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions; 87. 72-09-10, Damage from explosions;   88. 72-09, 8th SOS maintenance sign; 89. 72-09, At EOR looking off base; 88. 72-09, 8th SOS maintenance sign; 89. 72-09, At EOR looking off base;   90. 72-09, Capt Nicholai, Lt Jordan; 91. 72-09, Crew chief bath; 90. 72-09, Capt Nicholai, Lt Jordan; 91. 72-09, Crew chief bath;   92. 72-09, filling sand bags; 93. 72-09, filling sand bags; 92. 72-09, filling sand bags; 93. 72-09, filling sand bags;   94. 72-09, Lt Gordon (Flash); 95. 72-09, Lt Harrell with his aircraft (after loss of 339); 94. 72-09, Lt Gordon (Flash); 95. 72-09, Lt Harrell with his aircraft (after loss of 339);   96. 72-09, Maj Beland, Lt Haynes, Lt Harrell (driver); 97. 72-09, Msgt Stevens on top of new bunker; 96. 72-09, Maj Beland, Lt Haynes, Lt Harrell (driver); 97. 72-09, Msgt Stevens on top of new bunker;   98. 72-09, New bunker in front of maintenance building; 99. 72-09, Peace flag flying over munitions crew trailer; 98. 72-09, New bunker in front of maintenance building; 99. 72-09, Peace flag flying over munitions crew trailer;   100. 72-09, Sgt Huber; 101. 72-09, Sgt Price; 100. 72-09, Sgt Huber; 101. 72-09, Sgt Price;   102. 72-09, Sgt Rusk, Msgt Stevens, Ssgt Price, Toussinault, Roundtree, Huber; 103. 72-09, Sgt Salazaar getting to fly with pilot #2 acft 358; 102. 72-09, Sgt Rusk, Msgt Stevens, Ssgt Price, Toussinault, Roundtree, Huber; 103. 72-09, Sgt Salazaar getting to fly with pilot #2 acft 358;   104. 72-09, Ssgt on test flight with Capt Medkiff aft 814; 105. 72-09, Ssgt Rusk with Capt Medkiff aft 814; 104. 72-09, Ssgt on test flight with Capt Medkiff aft 814; 105. 72-09, Ssgt Rusk with Capt Medkiff aft 814;   106. 72-11, Alert pad damage, no one hurt; 107. 72-11, All pilots of 8th SOS; 106. 72-11, Alert pad damage, no one hurt; 107. 72-11, All pilots of 8th SOS;   108. 72-11, beautiful new bunker #1; 109. 72-11, News crew filming mission #6; 108. 72-11, beautiful new bunker #1; 109. 72-11, News crew filming mission #6;   110. 72-11, Skull & cross bones flag; 111. 72-11, Rocket damage on corner of revetment - maint bldg; 110. 72-11, Skull & cross bones flag; 111. 72-11, Rocket damage on corner of revetment - maint bldg;   112. 72 - Msgt Stevens, Sgt Gilsdorf, Ssgt Fergunson; 113. 72 - SSGT Price, Msgt Stevens, SSgt Rusk; 112. 72 - Msgt Stevens, Sgt Gilsdorf, Ssgt Fergunson; 113. 72 - SSGT Price, Msgt Stevens, SSgt Rusk;   114. 72 Sgt Treece, Msgt Stevens; 115. 72, A-37 loaded & ready; 114. 72 Sgt Treece, Msgt Stevens; 115. 72, A-37 loaded & ready;   116. 72, Acft 348 skid path; 117. 72, Acft 348 Pilot Lt Moorehead OK; 116. 72, Acft 348 skid path; 117. 72, Acft 348 Pilot Lt Moorehead OK;    118. 72, Bullet hole lt tank entrance; 119. 72, Bullet hole lt tank exit; 120. Rain in flight line area; 118. 72, Bullet hole lt tank entrance; 119. 72, Bullet hole lt tank exit; 120. Rain in flight line area;    121. 72, Papasan washing OPS truck, 360 on wash rack behind; 122. 72, Ssgt Roundtree & Msgt Stevens; 123. 72-Spring, Lt Perigrim wringing out wet uniform & boots 121. 72, Papasan washing OPS truck, 360 on wash rack behind; 122. 72, Ssgt Roundtree & Msgt Stevens; 123. 72-Spring, Lt Perigrim wringing out wet uniform & boots

The following are photos by Earl Watson, then a SSgt with the 8th SOS at Bien Hoa. He wrote, "I served as a A-37 munitions load crew chief from January 1972 until the deactivation. I went from Bien Hoa to Tan Sonhut to work with FACs. I DEROS'd Nam in January of 1973."

500 pounders and CBUs |

A-37 after 122mm Rocket |

A-37 hanging with F-4s |

Barracks Rocket Damage |

Bien Hoa Flightline |

Inspecting Shrapnel Damage |

Downloading Damaged Bird |

Pulling Safety Pins |

Anyone Remember this building? |

Early AM Rockets |

Rocket Attack fire |

Lighting up the night |

Flightline at Night |

Spare Parts |

Training New Guys on Arm and Dearm |

Daisy Cutters loaded on Right A-37 |

Poker with Cambodian A-37 Trainees

The War Goes On (1972) The Easter Offensive (Spring 1972) fighting was extremely nasty, but produced notable US battlefield victories. The American military managed to prevail in these struggles despite serious weakness caused by the US exodus from Southeast Asia. The US land component had shrunk from 550,000 troops at the height of the war in 1969 to only 95,000. During the same period, the strength of US air and naval forces fell to about one-third of their previous peak levels. The U.S. was desparately trying to disengage itself from the Vietnamese quagmire -- and the North exploited this weakness. In Military Region I, more than 40,000 North Vietnamese troops swarmed southward through the DMZ and eastward from camps in Laos. By April 2, the enemy had captured all intervening fire-support bases and was moving directly on Quang Tri City, the provincial capital. Interdiction by US Air Force fighter-bombers and B-52 bombers slowed the advance, but Quang Tri City was evacuated May 1. The enemy then reorganized for a drive on Hue.

In Military Region II, 20,000 Communist soldiers surged out of Laotian and Cambodian sanctuaries to attack the major cities of Kontum and Pleiku. The intent was to cut Pleiku off, then drive on to split South Vietnam in half. South Vietnamese troops fought well, stiffened by US advisors. Kontum, however, was cut off and surrounded. The city was sustained by a massive aerial resupply effort. In addition, the Communist military attack failed. US Air Force B-52s and tactical fighters combined with TOWtoting US Army UH-1s to defeat the northern invaders in the field, despite a monumental effort by huge numbers of North Vietnamese tanks and artillery.

In Military Region III, one regular North Vietnamese division and two Viet Cong divisions-some 30,000 men combined-sallied from their Cambodian salient to attack An Loc and Loc Ninh in hopes that a quick victory would lead to a drive down Highway 13 to Saigon itself. Hanoi sought an outright military victory in order to establish Communist control over South Vietnam, drive US forces from the South, and prevent the re-election of President Richard Nixon. They called the action the "Nguyen Hue Offensive" in honor of a Vietnamese hero who had inflicted a massive defeat on Chinese forces in 1789. The 1972 battles marked the final major US engagements of the Vietnam War. Moreover, they illumined the future of the Air Force more than anyone imagined at the time.

The U.S. forces in Vietnam were in deep trouble -- word was sent out. "SEND HELP NOW!!!" Easter Offensive: W. R. Baker stated:USAF assets were committed as soon as weather permitted. The combination of Tactical Air Control Systems, Forward Air Controllers, radar, and airborne command posts enabled American commanders to get the maximum effectiveness from the limited resources. B-52 bomber and tactical fighter attacks were provided in the most desperate situations as they arose, and gunships were allocated to the outposts under the heaviest fire. The gunships also provided mobile cover for retreating forces, laying down gunfire as roadblocks to the pursuing enemy armor.

While the in-theater forces were putting on a maximum effort, the orders went out for a worldwide mobilization of USAF units to return to Southeast Asia prepared to fight a vicious, protracted battle. The transfer of B-52s was called "Bullet Shot." The return of tactical fighters went by the name "Constant Guard" (I-IV). The 45 days following the start of the Easter Offensive saw the Air Force demonstrate global mobility and power on a massive scale. From bases in Korea, the Philippines, and the United States, additional fighters, bombers, gunships, electronic warfare birds, search and rescue units, transports, and tankers moved in a swift, smooth flow to Southeast Asia. In some instances, units were in combat just three days after they received orders to move.

The strike forces built up rapidly: Fighters doubled to almost 400, B-52 bomber strength increased to 171, and the number of tankers rose to 168. The Navy and Marines also responded, with the carrier force building to six.

In many instances, USAF's airmen were coming back for their second or third tours in the area, often to the same bases from which they had operated previously. The bases themselves were in varying states of readiness; after the years-long drawdown, the local population had stripped them of useful material, from radar gear down to household wiring, toilets, and window panes.

Air Force units returned to find runways intact, but not much else on hand, and tent cities sprouted where there had once been a complete base complex that had included air-conditioned hootches, clubs, theaters, and swimming pools.