8th Bombardment Squadron (L-NI)

Kunsan Air Base (K-8)

(1951-1954) |

8th Bombardment Squadron (L-NI):Acknowledgment: Thanks to James E. Gates for their photos of early Yokota Air Base at Bob Proctor's Website). Thanks to Bill DeAngelis and L.L. Dale for his photos of early Yokota Air Base at Don Cooper's Yokota AB site. Special thanks to Hans Petermann of San Diego, California for his technical notes on the B-26, photos and narratives that are used throughout the site. Also thanks to Jack Boyer of Santa Clarita, California for his photos and narratives to this section. Also thanks to Dave Bradburn for his narratives. We are extremely grateful to Al Gould for his narratives, commentary and photos. Thanks to Harold Locke for his photos. Thanks to Larry Casseria for his narratives and photos. Thanks to Paul T. Ono for his narratives. Thanks to Craig Hinton for his photos of the post-Korean years in Korea. In addition, we wish to express our gratitude to the late Jack Barclay of Bohemia, New York for his photos, maps and other invaluable reference materials. (Godspeed, Jack!) Thanks to the marvelous historical site of the 3rd Wing History Office of Elmendorf AFB, AK for its historical materials. We are deeply indebted to the Joe Baugher website for its wealth of historical information on aircraft. Thanks to the 13th Bomb Squadron Website for the use of their photos.  8th Bomb Squadron insignia 8th Bomb Squadron insignia

Approved June 21, 1954 (KE 8387)

Occupation ForcesMove to Atsugi AB (Sep 1945): The war ended on 15 Aug 1945. The first US personnel from the 3rd Bomb Group to touch down at Atsugi were four 3rd Bomb Group commanders and former commanders, Colonels John P. Henebry, Richard H. Ellis, Charles Howe and Lt Col Stan Kline. The four gunners were Sergeant Cliff Britian, Sergeant Joe Watkins, Staff Sergeant Jim Lynch and Staff Sergeant Sam Hagenbush. They landed their A-26s at Atsugi Field, Japan on 31 August 1945. This landing was not without controversy as other units claimed the folks were "grandstanding."

The rest of the 3rd Bombardment Group arrived at Atsugi Field on 8 September 1945. (Some reports state the main elements arrived at Atsugi, Japan on October 26, 1945.)

According to the Carl Pettypiece site on the A-20A, "The old 3rd Bombardment Group still retained its A-20s until the end of the war, becoming the last operational Army A-20 unit."

Douglas A-26 (USAAC Photo)According to the 3rd Wing History, "The 3rd Bombardment Group settled into a peacetime training routine in occupied Japan. By the end of the year, the last A-20 had been transferred out, and the group became an all A-26 outfit. The wartime personnel strengths declined rapidly as the Army underwent demobilization. By January, the 13th, 89th and 90th Bombardment Squadrons had been reduced to one officer and one enlisted man each. The remaining personnel were concentrated in the 8th Bombardment Squadron. By late March, the personnel situation had improved to the extent that the 90th Bombardment Squadron could be made operational again. The 89th Bombardment Squadron was reassigned to another group on 6 May 1946."

Move to Yokota AB (Aug 1946): In 1946, the 3d Bomb Wing (Light) considered naming Yokota Air Base after its WWII Medal of Honor winner, Major Raymond Wilkins, as the 3d Bombardment Wing was moving there. However, the name was not accepted due to a change in Air Force policy for overseas installations to name bases for localities. Instead, Wilkins Ball park was dedicated in his honor on May 17, 1947. This facility is still in use today. The only base to be named for an American in Japan was Johnson AB, 30 miles west of Tokyo.

L: Wilkins Park (1947); R: Yokota Army Air Base (1947) (Japanese Yokota AB Site)According to a document on Don Cooper's Yokota AB site, The 353rd Engineering Construction and 864th Aviation Engineering Battalion moved ahead with great speed and finished the runway for dedication on August 15th by Major General Kenneth B. Wolfe, Commanding Officer Fifth Air Force, who landed the first aircraft on the new strip. At this same ceremony, Yokota was named Wilkins Field in memory of Major Raymond M. Wilkins, Commander of the 8th Bomb Squadron of the 3rd Bombardment Group, who was killed in action over Rabaul. This never became a reality as a War Department policy dated prior to the Yokota's request stated that all fields occupied would be named after the nearest town, Colonel Edward H. Underhill, Commanding Officer of the 3rd Bombardment Group, now Commanding Officer of the 314th Composite Wing led 15 A-26s into the field in conjunction with the dedication. The 8th Squadron arrived in August with the remaining squadrons trickling in.

In October 1946, Colonel Bobzein was killed in a B-29 accident and Lt. Col. Warner L. Gates became Commanding Officer of Yokota until February 1st when Colonel Edwin H. Underhill assumed command. On June 2nd, Col. James R. Gun, Jr. took over as Yokota's Commander when Col. Underhill was transferred to the position of Commanding Officer of the the 314th Composite Wing.

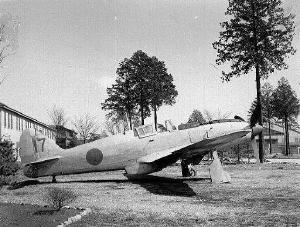

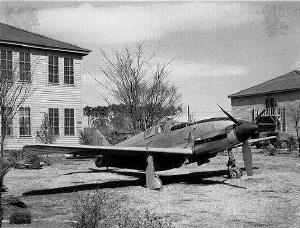

Yokota was opened in March 1940 by the Japanese Imperial Army as Tama Army Airfield. The name of the airfield was derived from Tama Prefecture -- or county in which it was located. At that time, the land area of the air base was approximately 446 hectares (1,102 acres), while the length of the runway measured 1,300 meters (4,265 feet). By the end of 1942, the airfield was operating at its peak as the "Wright Field" of Japan, where newly designed aircraft were first tested. When US Forces took control of the base in 1945, they found 280 of the most modern Japanese aircraft still in excellent running condition.

The Japanese had removed the tops of hangars to resemble bomb-damaged facilities, so US fighters thought they were already bombed areas. For the most part, the Yokota area suffered little damage during World War II from American bombers. The airfield was fully operational when the allies arrived.

Yokota was officially dedicated as an American base by Occupation forces on August 15, 1946. The base's name was changed from Tama Army Airfield to Yokota Air Base, after a small village located on the northeast corner of the base.

|  |  |  |

Occupation Force 1950s: TopR: Kawasaki KI-16 Hien at Main Gate (1947); Top L: KI-116 Main Gate; Middle R: Nakajima KI-115 at Yokota (1947); Middle L: Auditorium (1947); Bottom L: B-29 in hangar (1948(; Bottom R: HQ Bldg (1948) (James E. Gates photos at Bob Proctor's Website)U.S. operations began September 4, 1945, when U.S. forces occupied the area. The 3rd Bomb Group moved to Yokota AB, Japan on 30 August -10 October, 1946. Officially, the 3rd Bomb Group arrived on 1 September 1946. Training commenced to make the three remaining squadrons (13th, 90th, and 8th) combat-ready with the B-26 Invader. The unit would remain at Yokota until 1 Oct 1949.

Yokota AB 1950s (Bill DeAngelis photos at Don Cooper's Yokota AB site)

At the time, the new United States Air Force was being created from the Army Air Forces. The USAF came into being on 18 September 1947. With the creation of the United States Air Force, an internal reorganization occurred. The Air Force planned to have one wing for each of its bases, and assign various base organizations to the wing. As a result, the Air Force activated the 3rd Bombardment Wing (Light) on 18 August 1948. The 3rd Bombardment Group was assigned to the wing, which received the group's emblem and honors.

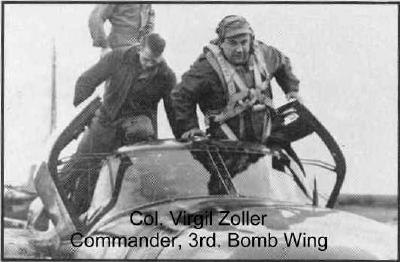

The following was excerpt was written by Louis Miksits on the 80th Headhunters Site who was assigned to the 80th FBS, 8th FBW at Ashiya AB when it first arrived in Japan. He talks about the Japanese relationship with the Americans and notes the "base commander" of Ashiya AB, Col. Zoller, the 3rd BW commander. (See Brig Gen Virgil Zoller.) "In 1948 (July) when I was first ordered to the 80th Fighter squadron at Ashiya Air Base, Kyushu, I thought at the time that we were neither liked or disliked. What I mean by that is the Japanese were just coming off the war and were more interested in making the best of it. They were short of everything; food, clothing, jobs, etc. The black market was booming. I think that Asiatics as a whole were natural thieves. They would steal everything that was not tied down. We had clothing, shoes, etc, stolen right from our barracks. It was not unusual to come back to the barracks and find things gone. One of the methods of punishment, when caught, was to put them head down in an empty 55 gallon drum and beat on the sides. This usually cured them.

As far as the ugly Americans or beautiful ones, I can only remember that we had both. In any occupation, you will have the good and the bad. I must say that the good was more predominate. We helped the orphanage and little league ball teams and in general were treated fair. Those out of line were nailed by the military police.

The town was called Ashiya Machi. We had another town across the bridge over the river Ongagowa called Ashiya Korea. We were told not to go over there because of the hard feelings between the Japanese and the Koreans. The Koreans being more or less servants and laborers during the time Japan dominated them. A lot of fights and hard feelings between them. We were put on standby a few times because of riots. On occasion, the field was raided and damage done to the aircraft. Some Americans got killed at the POL and bomb storage areas (throats cut).

I think by far that the time and place things were about normal for the occupation. The Japanese were given jobs on the base and obeyed the people who supervised them. Pulling guard duty on the POL and bomb dump were a little hazardous because one man was at the gate area and the other walked the area. It was a long way from the main base and a long way around. The only communication between you and the other post was by firing your weapon. An instance occurred in 1949 where the officer of the day tried to sneak up on the guard at the gate and was shot. He survived, don't know his name, but he was a captain from the 80th. You got kind of nervous out there. I'm sure he never tried that again.

There never was too much of a problem between us and the nationals. They resented us calling them gooks. After all, we were really the gooks and they were the nationals. Many of the men had Japanese girlfriends or Kobitos. The word was the find yourself a nice clean girl and stick with her because if you caught VD your ass was mud. The Japanese people frowned on their women going with GIs, but he in turn fed her and her family. I am sure many of them got married and brought them back to the states. As the years went by, the relations between our two countries did improve.

...

I think that I sort of enjoyed the occupation as the years went by. I was based at Tachikawa, Johnson, Yokota, Itazuke, and Misawa during my tour, before the Korean War started. I did a lot of traveling throughout the Pacific and learned the Japanese language and customs. I never got used to their stealing, having lost some precious items along the way. Traveling to the mountains and villages was great. I met a lot of interesting people and the one person I will never forget is Colonel Virgil Zoller, Ashiya Base Commander. I am sure a lot of men from the 80th remember him also.

|  |

Occupation Force 1950s: TopR: Fujisan; Top L: Smells of Honey Wagon (Human Waste) used in Rice Fields Bottom L: Base of Emporer's Palace, Tokyo; Bottom R: Kamakura Buddha (L.L. Dale photos at Don Cooper's Yokota AB site)On 14 Mar 1950 the unit moved to Johnson AB, but only temporarily. The 3rd Bombardment Wing moved to Johnson Air Base, Japan, on 1 April 1950. The move was to make room for the 35th Fighter Wing that moved into the base. At Johnson AB, the unit trained in bombardment and reconnaissance with its B-26s. The training switched to night interdiction in June. On 25 June 1950, the Air Force redesignated all the squadrons as bombardment squadrons (light, night intruder). Thus the squadron became the 8th Bombardment Squadron (L-NI). That same day, North Korea invaded South Korea during the early morning hours.

B-26 Overfly of Yokota AB (Japanese site)On June 22, 1950, the 8th Bomb Squadron went on TDY to Ashiya AFB, Japan for the FEAF (Far Eastern Air Force) readiness test. The Squadron was in position on June 24th but due to adverse weather conditions was unable to complete the test. On the 25th of June, the Korean hostilities broke out. President Harry Truman authorized the US Air Force and Navy to support the rapidly retreating South Koreans. The 8th Bomb Squadron gained the distinction of flying the first combat mission over Korea -- and tragically receiving the first casualties of the war.

When the Korean conflict broke out, it was planned to base the squadron at Ashiya, but then orders came through to move. In March 1950, the unit moved to Johnson AB, Japan; and then in July, 1950 the Squadron personnel and equipment were moved to Iwakuni.

Korean WarB-26s Prepositioned at Ashiya On June 22, 1950, the 8th Bomb Squadron went on TDY to Ashiya AFB, Japan for the FEAF (Far Eastern Air Force) readiness test. The Squadron was in position on June 24th but due to adverse weather conditions was unable to complete the test.

On the 25th of June, the Korean hostilities broke out. Upon being notified of North Korea's attack, the U.N. Security Council immediately called for the end of aggression. While the U.N. was debating this issue, the evacuation of Korea was underway. The first missions flown by the 8th Bombardment Squadron were escort duty for the ships returning personnel from Korea to Japan. According to the Korean Military Assistance Group (KMAG) at the time, "The movement of the American dependents from Seoul to Inch'on began at 0100, 26 June, and continued during the night. The last families cleared the Han River bridge about 0900 and by 1800 682 women and children were aboard the Norwegian fertilizer ship, the Reinholt, which had hurriedly unloaded its cargo during the day, and was under way in Inch'on Harbor to put to sea. At the southern tip of the peninsula, at Pusan, the ship Pioneer Dale took on American dependents from Taejon, Taegu, and Pusan. American fighter planes from Japan flew twenty-seven escort and surveillance sorties during the day covering the evacuation."

However, General MacArthur only had authority to support the KMAG up to the waterline of Korea. He could not act on his own initiative and order the air units in Japan into action -- the could only cover the evacuation. Finally, on June 27th the U.N. asked its members to go to the aid of the Republic of Korea. MacArthur received the Joint Chiefs of Staff directive which instructed him to assume operational control of all U.S. military activities in Korea.

The 3rd Bombardment Group (Light-Night Intruder) was crucial to the United Nations effort throughout the Korean Conflict. On the 27th, the 8th was called on to aid in the Korean police action from their TDY location at Ashiya, Japan. The first combat mission of the 3rd Bomb Group was flown by the 8th on June 27, 1950 against the rail yards at Munsan. The first losses were due to adverse weather conditions rather than to enemy action.

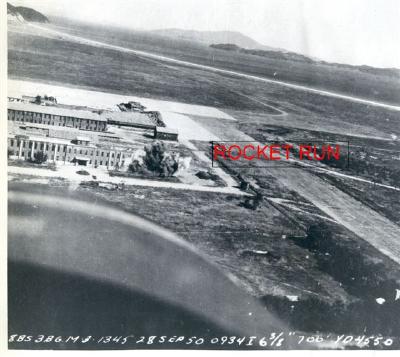

According to Frank Evans, "These two pictures were taken on the first bombing mission of North Korea

on 28 June 1950. The air Base is at the North Korean Capital at P'yongyang. The mission was Med Alt

at 12000 ft, in formation with a Bombardier. We had Med Flak with 3 or 4 Yak 9 s in the Area ..

We had no losses." (Courtesy Frank Evans)On June 28, 1950 B-26 aircraft of the 13th and 8th Bomb Squadron attacked the enemy with 12 aircraft and had the first fatalities of the Korean Conflict that day when an aircraft crashed returning to Ashiya, Japan. The first missions were flown against North Korean troops in the Han river area and other targets of opportunity. At that time the Republic of Korea (ROK) Army was in full retreat. From June 28 to 29, 1950 Seoul was captured by the advancing North Korean Army. The ROK was destroyed. On June 29, 1950, planes of the 3d BG attacked the North Korean field at Pyongang making it the first United Nations strike at the Communist forces above the 38th parallel. Within days, the 3rd had recorded the first Korean war combat casualties, a crew from the 13th BS was killed when their B-26 crashed on landing at Ashiya, Japan. The 3rd BG also scored the first B-26 aerial kill of the Conflict, a Yak fighter shot down by Sgt Nyle Mickly.

On the 28th of June, the 3rd Bomb Wing had recorded the first Korean war combat casualties, a crew from the 13th Bomb Squadron was killed when their B-26 crashed on landing at Ashiya, Japan. Lost were lLt Remer Harding, and SSgt William J. Goodwin. On the same day, the 8th lost two men south of Seoul, lLt Raymond J. Cyborski and SSgt Jose C. Campos. In addition, 1Lt Vernon A. Lindvig and 1Lt Derrell B. Sayre of the 339th Fighter Squadron (All Weather) from Yokota AB, Japan were lost. These six men were the first casualties of the Korean Conflict. The 7th Air Force erected a stone monument outside the Osan AB Chapel in their honor in June 2000.

Dave Bradburn, Maj Gen, USAF (Ret) remembers the brave men from the 8th. He wrote, "I was at Johnson Air Base near Tokyo with the 8th, but not flying combat missions at the time. I did bring the message about Cyborski and Campos to their families. Cyborski and Campos were on the same plane, probably a single-control model. There was also a navigator on the plane who survived the crash by bailing out. He was Harry Lister. I recall that he said later he believed Cyborski had his parachute tangled in the upper turret. No one saw Campos leave the plane, but he might have. I believe there probably would not have been a copilot on Cyborski's plane." Ed Shook added, "On 28 June,l950, l/Lt. Raymond J. Cyborski and his crew bailed out of a B-26 Aircraft approximately 50 to l00 miles south of Seoul, Korea. ... Ray Cyborski was never found and later was listed as missing in action. I believe that was changed to killed in action, sometime later."

Ceremonies at Monument Ceremony (10 June 2000)

Ceremonies at Monument Ceremony (10 June 2000)The following words were placed on a memorial stone marker at the Osan AB Base Chapel on 28 June 2000. Deryl Danner, 7AF/51FW Historian sent the following, "I appreciate the input I received from so many people in our efforts to analyze to a factual conclusion, a seemingly impossible task. Freedom is not free, and with this small token, I hope, further honors those past warriors who gave their all." "IN REMEMBRANCE"

The First American Losses of the Korean WarOn 28 June 1950, six airmen became the first Americans to lose their lives in defense of the Republic of Korea. They flew B-26 Invader light bombers assigned to the 3rd Bombardment Wing, and F-82G "Twin-Mustangs" from the 339th Fighter Squadron (All Weather), 5th Air Force, operating from Japan. In terrible weather, 5th Air Force launched heavily laden B-26s to attack the Munsan rail yards and F-82s to protect the freighter Reinholt evacuating non-combatants. Two B-26s and one F-82 were lost during the mission, killing six crewmembers aboard. They were:1Lt Raymond J. Cyborski, 8th Bomb Squadron

1Lt Remer L. Harding, 13th Bomb Squadron

1Lt Vernon A. Lindvig, 339th Fighter Squadron (All Weather)

1Lt Derrell B. Sayre, 339th Fighter Squadron (All Weather)

SSgt Jose C. Campos Jr., 8th Bomb Squadron

SSgt William J. Goodwin, 13th Bomb Squadron

|

They were the first of 1,200 USAF combat deaths for the war. They, along with 116,355 soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines of 22 nations, gave their lives so that peace, democracy and prosperity could flourish south of the 38th Parallel. Their courage and sacrifice is a continuing reminder that freedom is not free.

On June 30, 1950, President Truman ordered ground troops into action at Osan. As the first American soldiers of Task Force Smith encountered the enemy, overhead were the 8th Bombardment Squadron's B-26 attack bombers. From Yokota Air Base, Japan they hit the North Korean forces with napalm, high explosives, rockets and incendiaries.

When the Korean conflict broke out, it was planned to base the squadron at Ashiya, but then orders came through to move.  The Pacific Stars & Stripes caption under this photo in 1952 read, The Pacific Stars & Stripes caption under this photo in 1952 read,

"NAPALM ATTACK -- One of the 3d Bomb Wing "Grim Reapers"

clobbers a Communist-held observation point with napalm

during the early months of the Korean war."Move to Iwakuni In March 1950, the unit moved to Johnson AB, Japan; and then in July, 1950 the Squadron personnel and equipment were moved to Iwakuni. Flying daily missions they pounded the enemy troops and tanks, ripping up his supply lines, and blasting his supply depots.

During the bleak intial days of the war, the U.S. forces were ill-prepared to fight with ill-trained soldiers and outdated equipment. The U.S. forces were being pushed back into the Pusan Perimeter. The idea was to bring all the air elements under the central control of the 8th Fighter Wing at Iwakuni.

The 8th Bomb Squadron moved to Iwakuni where it flew its B-26 missions against the North. After Kunsan AB (K-8) Korea was constructed with a suitable runway, the unit relocated to Korea on 18 Aug 1951.

At the beginning of World War II, the Japanese built a Naval Air Station here, which was used as a training and defense base. That same year, 1940, the city of Iwakuni itself was created by the combination of two small towns and three villages. The largest town, with a recorded history dating back to 1600, gave its name to the new city-Iwakuni. The base, home to 150 Zero Fighter planes, was attacked only once during the course of the war, in July 1945.

Left: Iwakuni Main Gate; Right: Iwakuni Skyline (Courtesy Frank Evans)

Left: Bicycle Shop right outside the Main Gate; Right: Lady buying fish from Fish Salesman (Courtesy Frank Evans)

Left: Logging Boat; Right: net fishing from bridge (Courtesy Frank Evans)

Hiroshima Steam-driven Charcoal Cab (Courtesy Frank Evans)

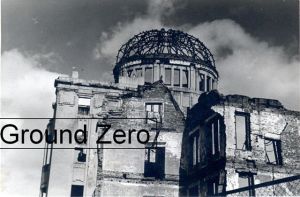

Left: Hiroshima A-bomb Bldg; Right: Hiroshima Inaribashi Train Station (Courtesy Frank Evans)

| The picture of the Inaribashi...Capt Bill Neighbors is standing in the Entrance. The shot of Ground Zero where the Atom Bomb was dropped during WW 2. |

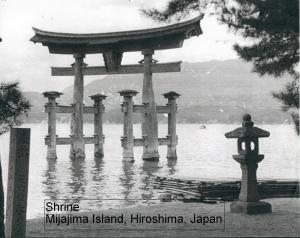

Left: Iwakuni Kintaikyo Bridge; Right: Mijaoma Island Tori Gate (Courtesy Frank Evans)During the remainder of the month of June, the Squadron flew forty sorties and acquitted itself well in spite of a shortage of ground personnel and maintenance men. Before many missions had been flown, this shortage of trained crews, ground personnel and equipment became apparent. However as the Squadron became better organized and help arrived from the United States, it soon turned into an efficient organization. The 8th soon started flying daylight low-level bombing and strafing attack missions against the main enemy supply routes, bridges, marshalling yards and all types of vehicular transportation.

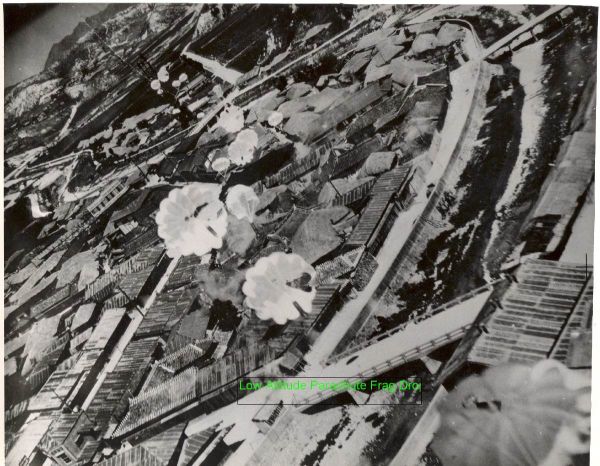

Low Altitude Fragmentation Bomb Drop (Courtesy Frank Evans)In The Korean Air War by Robert Dorr and Warren Thompson (p13), it states, "Douglas B26 Invader crews were in the conflict almost immediately, as recalled 1st Lt. Hammond H. Bittman, a navigator/bombardier for the 13th Bombardment Squadron:

"(At the beginning of the war), our 13th BS was at Iwakuni, Japan, on maneuvers. Our mission was photographing shipping between Japan and Korea. When we were ordered back to Yokota, Japan, our home base, we were told to pack a bag for 30 days and go back to Iwakuni (which is closer to Korea).

"We could not fly on 25, 26 or 27 June 1950 because of bad weather. The 28th was also bad but clear on top of heavy clouds. Off went Monte Ballew, pilot, and me, bombadier/navigator. It was clear enough beyond the 32nd Parallel to see the ground. We spotted a train going south and proceeded to drop 500lb (227kg) bombs in front and back of the train, stopping it. We strafed up and down into the stalled train.

"That's when we got hit by heavy machine gun fire that shot up one engine and left the aircraft with just one flyable engine. We left the area while we could still control the aircraft. On the way back, we landed at Suwon and were elated to see American eagles on the personnel who ran to our airplane. We were introduced to a General Church (Brig. Gen. John H. Church, an Army ground commander). He was as confused as everyone. When he asked his aides how many troops he had, how many tanks, etc., there was no coherent answer. Things were a mess."

Later Bittman recalled after returning from Suwon, "I returned to our temporary base at Iwakuni and being unshaven, tired, and needing a bath, was asked, where had I been? I was scheduled to lead the squadron to Pyongyang, North Korea. I cold not believe it, but that was how short we were of flying personnel. There had been a RIF (reduction in force) a few months before that. Flying crews had to load, fuel, and fly the aircraft. That's how short we were.

"We bombed the runway at Pyongyang and some buildings, doing damage to some extent. When the war settled into place, we flew two missions a day over North Korea starting at 0500hr. What with a briefing, flying, debriefing, and briefing for a subsequent night flight, it was a long, long day and there was not much time for sleep."

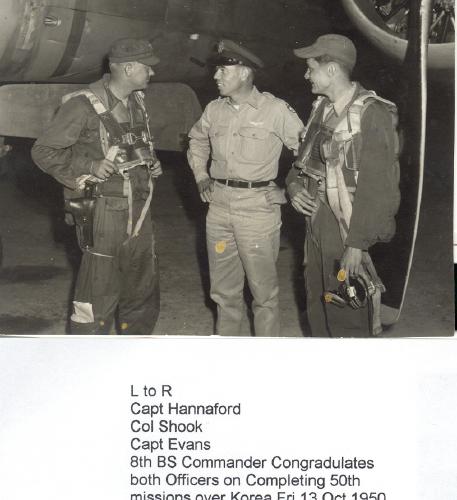

In "B-26 Invader Units Over Korea" (p14) by Warren Thompson, it states that Lieutenant Bittman recalled how after landing from his scheduled mission on 28 June, he then had to fly the mission over Pyongyang with no crew rest. He remembered that the squadrons were so short handed due to an earlier reduction-in-force that the flight crews had to assist in refueling and weapons loading of their aircraft. He also remembered that the original crews had flown so many missions back-to-back, that by early August they had already met the 50-mission requirement.

According to The Three Wars of Lt. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer, His Korean War Diary, edited by William T. Y'Blood, 1999, (p50) stated in Gen. Stratemeyer's words on 2 July 1950, "Morale of 8th Fighter Wing and 3d Bomb Wing "superior". In spite of strenuous flying and fighting that has been done, they were all raring to go."

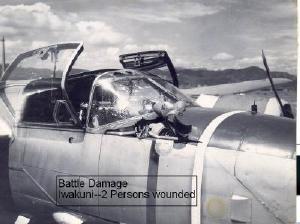

Battle Damage Iwakuni -- 2 wounded -- Note how metal peeled back

at canopy edge showing exit hole. (Courtesy Frank Evans)According to "The United States Air Force in Korea, (p87), Futrell, although the B-26 had proved highly effective in low-level operations, the crews found it difficult to maneuver at low-level in the mountainous terrain of Korea. Additionally, small-arms fire took a heavy toll. Those responsible decided that the light bomber should operate at medium altitude. The 3rd Bombardment Group possessed seven or eight glass nose B-26Cs at the time capably of bombing from medium altitude. Various options were tried, including having the B-26B crews bomb on command from a B-26C bombardier. Lieutenant General Stratemeyer, at this junction, ordered the 3rd Bombardment Group to focus on destroying rail and road bridges south of the Han River to slow down the steadily advancing North Koreans. The B-26B pilots devised new tactics, which required them to execute the attack in a shallow dive and align the bomber with the target allowing for drift and angle. The tactics proved successful.

On 2 July 1950, the Fifth Air Force ordered the 3rd Bombardment Group to move from Ashiya Air Base to Iwakuni Royal Australian Air Base. "Since the Australians occupied the base, the group had to solve logistical and housing problems without the support of a US host unit. In addition, half the personnel conducted the move while the other half continued to support 24-hour combat operations. (Hist, 3BG, 25 Jun-31 Oct 50, Ch 1, p. 3.)"

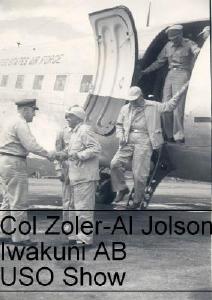

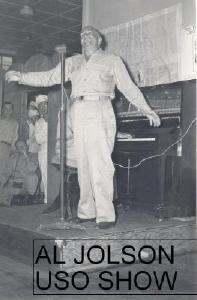

Al Jolson USO Show Left: Col Zoller Greeting Al Jolson;

Right: Al Jolson Singing "Mammy" (Courtesy Frank Evans)

Left: Lt Evans with Bike; Right: Japanese Housemaids (Courtesy Frank Evans)

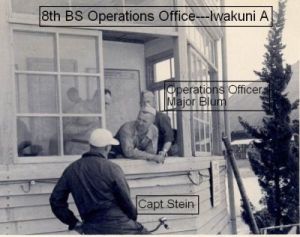

8th Ops Office: Iwakuni A: Operations Officer Major Blum

with Capt Stein (Courtesy Frank Evans)From 1 Jul 1950-19 Jul 1950, the 3rd Bombardment Wing performed reconnaissance and interdiction combat missions from Iwakuni AB, Japan. From 20 Jul to 1 Dec 1950 the tactical group and its squadrons served under operational control of the 8th Fighter Wing. The wing assumed a supporting role, initially from Johnson AB, Japan, but later from Yokota AB, Japan. The wing returned to Iwakuni AB on 1 Dec 1950, regained control of its combat units and performed night intruder combat missions.

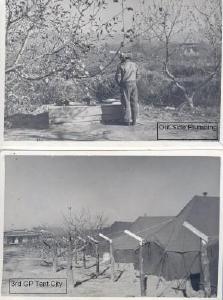

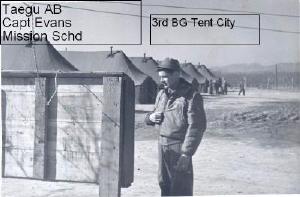

According to Frank Evans, Col, USAF (Ret), "Our Tent City, at Taegu, AB that was used as our turn around Base. We usually left Iwakuni on a night mission and returned to Taegu where another crew took the aircraft on a turn around and then returned to Iwakuni, when the crews piled up at Taegu they were airlifted back to Iwakini to keep the crews in balance."

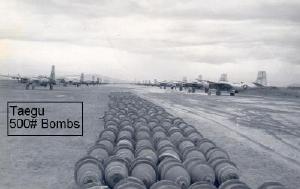

3rd Bomb Group at Taegu (K-2) (Courtesy Frank Evans)According to the 3rd Wing site, "Between 27 June and 31 July, the 3rd Bombardment Group destroyed 42 tanks, 163 vehicles, 39 locomotives, 65 bridges, 14 supply dumps and killed or wounded nearly 5,000 enemy troops. The 3rd Bombardment Group had effectively made the transition from the peacetime training environment to combat. It had fully exploited the versatility of the B-26, flying 676 effective day and night sorties that included interdiction, low-level attack, close air support and night intruder. The achievement earned the 3rd Bombardment Group its third Distinguished Unit Citation and the Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation."

(Courtesy Frank Evans)

(Courtesy Frank Evans)Pusan Perimeter Defense: In July, the North Korean People's Army (NKPA) continued their advance and the Fifth Air Force concentrated on interdicting North Korean supply routes by destroying major road and rail bridges. The outnumbered U.S. forces retreated into the defensive line called the "Pusan Perimeter." The defense line was horseshoe-shaped with Taegu at the apex. The remnants of three defeated U.S. regiments (the 21st, 34th & 19th) -- each one little better than a battalion in size -- fell back to make their stand at the Naktong River and Taegu. The condition of the troops were dire.

U.S. Air Force in Korea (pp135-136) states, "Late in July a few 3d Bombardment Group crews who had been assigned to the 47th Group began to fly night-intruder sorties." (The 47th BG (Light) flew B-26s in World War II in Italy's Po River Valley.) "The 3d Group B-26's were quite different from the planes they had flown in the 47th Group, for they had no radar altimeters, short-range navigation radar (shoran), or AN/APQ-13 blind-bombing radar, but in their initial employment over Korea the 3d Group crews met apparent success. They could see the lights of a Red convoy and even though the hostile vehicles almost always blacked out before the B-26's could make a pass the light-bomber crews felt that they could remember the convoy's position well enough to get in one good strafing pass."

In August, the North Korean Army continued to launch attacks against the Pusan Perimeter, achieving some success, but at the same time becoming steadily weaker. The Fifth Air Force had succeeded in crippling its armor capability and forcing it to move supplies at night. With air superiority achieved, the Eight Army enjoyed the ability to move its forces within the perimeter without fear while the Fifth Air Force pounded the North Korean Army on a 24-hour basis with interdiction and close air support strikes. In the mean time, UN reinforcements were arriving through the port of Pusan.

At the start of the Korean Conflict, the USAF possessed no night-intruder organization. During July, the 5AF used some F-82s for offensive night operations, but General Partridge (5AF Commander) did not think these planes had much value. Early in August, when the VMF(N)-513 began to operate from Itazuke, the all-weather Corsairs provided eight to ten sorties per night, but more effort was needed. The F-80s tried their hand, but they found it impossible to strafe enemy road traffic. F-51 Mustang pilots had "almost nil" results in night-harassment missions.

Rocket run (Courtesy Frank Evans)U.S. Air Force in Korea (pp135-136) states that though Lt. Gen. Stratemeyer (Commander FEAF) was reluctant to reduce his daylight attacks in August 1950, he "directed the 3d Group to place half its effort on night operations. The 8th and 13th accordingly alternated in the night-intruder role, one squadron flying night missions one week and day missions the following week. By using the light-bomber squadrons in addition to the all-weather squadrons the Fifth Air Force managed to fly an average of 35 night-intruder sorties each night during August."

The book continued, "Each intruder organization dispatched its crews singly at periodic intervals during the night to reconnoiter prebriefed transportation routes -- the assigned mission being to harass enemy convoys and force them to move without their lights, thus increasing the enemy's problem of resupplying his combat forces."

In August 1950, the 13th Bomb Squadron flew the first night intruder mission and alternated with the 8th Bomb Squadron. On average, 18 aircraft were scheduled for night intruder work each night, with aircraft taking off every 15 minutes. The group dispatched missions on a 24-hour basis. (Hist, 3 BG, Aug 50, p. 4)

U.S. Air Force in Korea (pp135-136) states "As August wore on 3d Group night intruders, who had begun to supplement their strafing attacks with 160-pound fragmentation bombs, reported that they were sighting fewer and fewer lighted convoys. Communist night convoys were now creeping and not speeding to the front lines. Other evidence indicated the North Koreans, already hypersensitive to daytime air attack, had an unreasonable fear of the night intruders."

Col. Virgil Zoller (later Brig Gen), 3d BW Commander Col. Virgil Zoller (later Brig Gen), 3d BW Commander

Iwakuni AB, Japan

(From 731st BS (L-NA) Homepage)

Click on Photo to enlargeOn 14 August 1950, Colonel Virgil L. Zoller assumed command of the 3rd Bombardment Wing, replacing Colonel Strother B. Hardwick, Jr. The 3rd Bombardment Wing moved to Yokota Air Base. (See Brig Gen Virgil Zoller.) The 3rd Bombardment Group remained at Iwakuni Air Base. 23 August 1950: Colonel Donald L. Clark assumed command of the 3rd Bombardment Wing, replacing Colonel Virgil L. Zoller who moved to setup the 452d BW operations.

On 1 August 1950 the 8th started flying night intruder missions. The 8th flew this type of mission for the remainder of the war except for an occasional special mission. According to an article "Korean Targets for Medium Bombardment," (p. 66), nightly visual reconnaissance of the enemy supply routes were ordered, beginning on 6 August. On the 8th, night sorties were increased to fifty for ALL bombers (B-26 and B-29); by 24 August, Fifth Air Force B-26's alone averaged thirty-five sorties nightly. Late in August the Air Force began flare missions over North Korea. B-29's would release parachute flares at 10,000 feet that ignited at 6,000 feet, whereupon co-operating B-26 bombers attacked any enemy movement discovered in the illuminated area. These M-26 parachute flares from World War II stock functioned poorly, many of them proving to be duds.  B-26B "Shook Up Shark" B-26B "Shook Up Shark"

(Courtesy Lou Segaloff)

Click photo to enlarge According to an article "Korean Targets for Medium Bombardment," (p. 21-22), On 15 August FEAF included the B-26 in interdiction attacks against all key bridges north of the 37th Parallel in Korea. This campaign sought the destruction of thirty-two rail and highway bridges on the three main transportation routes across Korea: (1) the line from Sinanju south to Pyongyang and thence northeast to Wonsan on the east coast; (2) the line just below the 38th Parallel from Munsan-ni through Seoul to Ch'unch'on to Chumunjin-up on the east coast; (3) the line from Seoul south to Choch'iwon and hence east to Wonju to Samch'ok on the east coast. The interdiction campaign marked nine rail yards, including those at Seoul, Pyongyang, and Wonsan, for attack, and the ports of Inch'on and Wonsan to be mined. This interdiction program, if effectively executed, would slow and perhaps critically disrupt the movement of enemy supplies along the main routes south to the battlefront.  Capt Fred Permenter - Pilot (1952) Capt Fred Permenter - Pilot (1952)

(Courtesy Hans Petermann)

Click on photo to enlarge

However, later analysis of this idea would reveal that air interdiction in Korea was not effective because it was not combined with ground initiatives as part of an overall strategy of attrition. But this was balanced out by profound role airpower played in the war. In a paper entitled, "Air Power in Peripheral Conflict: The Cases of Korea and Vietnam.", it stated, "What role, if any, did air power bear in that conflict? Its shortcomings are generally well-known: There were few strategic targets worthy of the name in Korea, and interdiction, while seriously draining the Communist forces of supplies, was never able to totally inflict supply denial upon them. Further, Communist antiaircraft fire took a high toll of attack aircraft, even if Communist fighters (in contrast to Nazi and Japanese fighters in World War II) did not. (UN forces lost approximately 1,200 aircraft to enemy action, only 147 in air-to-air combat). But in many other respects, air power was of profound importance. Postwar assessment found that the majority of Communist losses came from United Nations air attack: 47% of troops killed, 75% of tanks destroyed, 81% of trucks lost, and 72% of artillery destroyed. More significantly, it is not merely arguable but highly likely that South Korea was, in fact, saved by joint and coalition air operations during the critical opening weeks of the war, from late June 1950 down through the bitter fighting on the Pusan perimeter in August and September of that year before MacArthur's Inchon invasion. Further, after the Chinese Communist intervention in the late fall, United Nations air attacks seriously blunted the communist offensive and, in the case of the eastern withdrawal from the port of Hungnam, enabled the retrieval of what otherwise would have been entrapped forces. ..."

It goes on to say, "United Nations fighters, spearheaded by U.S. Air Force F-86 Sabres, consistently dominated their Communist opponents, many of which were Soviet-built MiG-15 fighters flown by Soviet airmen. Thus, throughout the war, United Nations bomber and attack aircraft were free to essentially operate unmolested except from the risks of antiaircraft fire and, at most, only sporadic fighter attack (unless they were operating in or near the so-called 'MiG Alley' in northwestern Korea). United Nations ground forces therefore had a near-constant UN air presence above them, assisting them in their fight on the ground via airborne forward air controllers working with incoming, on-call, or orbiting strike flights. ..."

On September 6 General Vandenberg (USAF Chief of Staff) suggested that the 3d Group be completely converted to night attack. As soon as it reached the theater, the 452d Bombardment Wing could make up for the lost daytime effort. General Stratemeyer was completely in agreement as one of his main requirements was "equipment and tactics to seek out, see, and attack hostile ground equipment at night."

By mid-September, the NKPA forces had paid a terrible price in trying to overcome the Pusan perimeter. "This Kind of War -- The Classic Korean War History" (by T.R. Fehrenbach, 1963) put it this way, "The NKPA had overrun all South Korea except one tiny toehold in the southeast corner -- but the toehold had given it unexpected trouble. Its timetable calling for the Communization of all Korea by 15 August had been wrecked. Worse, the Inmun Gun, the People's Army, had left the bones of its best men scattered along the Naktong River, and the survivors were rapidly bleeding themselves to death against American guns ..." Less than 30 percent of the old China veterans remained, and these were dirty, tired, hungry, and in rags. The NKPA had suffered about 60,000 casualties, most of which had been inflicted by ROK's. Its total combat strength could not have been more than 70,000 with only forty tanks left. On the other hand, the United Nations force had 141,808 of which some 82,000 were ROK's. American combat ground strength was 47,000.

Inchon Invasion and Pusan Breakout (15 Sep 1950): On September 15, 1950 the US 1st Marine Division, ROK marines and 7th Infantry Division troops led the "surprise" attack at Inchon. Despite this lack of secrecy, the landing met with little resistance and was resounding success with few casualties. As word of this spread to the North Korean forces, their forces completely shattered. On September 18, the U.N. broke out of the Pusan Perimeter. By September 23 the NKPA (Inmun Gun) was everywhere in full retreat. US, ROK, and UN forces launched counterattacks against the North Korean forces from the Pusan Perimeter in order to link with the UN forces at Seoul and Inchon

On 16 September 1950, the Eighth Army launched an offensive to break out of the Pusan Perimeter and link up with the Inchon forces 150 miles away. | (Click on photos to enlarge)Top Right: An F-80 leads a formation of 3d BG B-26s against targets near Iri on September 16. White spots just to the left of the fighter and under its wing mark rockets just fired at some enemy tanks. Top Left: The bombers attack the Iri rail yards. Bottom Right: A parabomb floats toward a bridge near Iri. The North Koreans have spanned a destroyed portion of the bridge with a crude but effective earth and timber structure. Bottom Left: 3d BG Invaders wheel around to attack flak installations near Iri. |

According to "The U.S. Air Force in Korea" (p136), Futrell, in September 1950: General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, Air Force Chief of Staff, recommended to Lieutenant General Stratemeyer that the 3rd Bombardment Group be converted completely to night operations. He also suggested that the 731st Bombardment Squadron (Light-Night Attack) be attached to the group since it had been trained low-level night operations. The 452nd Bombardment Wing would assume the daylight mission and the 3rd Bombardment Wing would fly night missions.

On 1 September 1950, four crews and aircraft from the hastily activated 731st Bombardment Squadron departed George AFB, California for Japan. The 731st BS was detached from the 452d BW and ordered to join the 3rd BW. When they arrived, they were attached to the 3rd BG and began flying operations the next day to gain combat experience until the arrival of the rest of the squadron. The remainder of the squadron arrived at Iwakuni on 17 November 1950.

According to the 3rd Wing site, "During the month of September, the 13th Bombardment Squadron flew 60 medium altitude, 99 low-level, and 298 night intruder sorties. During these missions they dropped 422 tons of explosives. The 8th Bombardment Squadron flew a similar number of sorties. The 3rd Bombardment Group reported three crewmembers missing in action from the 8th Bombardment Squadron and three missing in action from the 13th Bombardment Squadron. The group lost three aircraft destroyed and two damaged. (Hist, 13BS, Sep 50, p. 1; Hist, 3BG, 25 Jun-31 Oct 50, Ch 2, p. 6; Summary of Events, 3BG, Jun 50-Mar 51.)"

"The night intruder missions taxed the B-26 crews to their limits because of the distances that had to be flown. The crews had to land at Taegu (K-2) to refuel. Because the field was not adequately equipped, their return to Iwakuni was delayed, further hampering operations. The problems increased as the North Korean withdrew in the face of the United Nation's offensive. Bombers often returned to Iwakuni with their fuel tanks almost empty. (Hist, 3BG, 25 Jun-31 Oct 50, Ch 1, pp. 1 and 7.)"

"Between 25 June and 31 October, the 3rd Bombardment Group lost 42 B-26s directly and indirectly to enemy action, of these 29 were combat, 3 were used for parts and 10 had to be sent to depot for major repair. In return, the group received 50 replacement B-26s of which 44 were assigned to the two squadrons. (Hist, 3BG, 25 Jun-31 Oct 50, Ch 5, p. 4.)The 3rd Bombardment Group reported two killed in action, twenty-five missing in action and seven wounded in action since the start of hostilities. (Hist, 3BG, 25 Jun-31 Oct 50, Ch 2, pp. 5-6.)"

Chinese Lay a Trap The UN forces including three ROK divisions pursued the fleeing North Korean forces. But unknown to the UN forces, the Chinese 40th, 39th and 42d armies -- the equivalent of nine U.S. divisions -- under Commander-in-Chief Peng had marched under the cover of darkness into North Korea on 19 October. They went undetected by American fliers and MacArthur was convinced there was no threat of Chinese intervention. This is what he told President Truman in his meeting with him on October 15 at Wake Island.

On October 21 Pyongyang fell to UN forces. The race to the Yalu continued despite the warnings of a Chinese presence. On October 24 The Eight Army crossed the strategic Chungchon River and one division, the ROK 6th Division had reached the Yalu River on the Manchurian border. MacArthur rejoiced and authorized the use of "any and all ground forces to secure all of North Korea." On October 26, the X Corps landed at Wonsan on the east coast.

After the breakout from the Pusan Perimeter in November 1950, the 8th flew daily strike missions. Dave Bradburn (then a flight commander with the 8th) remembers flying missions out of Iwakuni and at times recovering in K2 (Taegu). In the Crimson Sky -- The Air Battle for Korea by John R. Bruning, it relates these missions. It stated (p113), "The 3d Bomber Wing operated out of Iwakuni Air Force Base, Japan, until late in the summer of 1951, which forced the crews to fly long, arduous missions that sometimes lasted more than six hours. When the Chinese had attacked that spring, FEAF requested that the light bomber wings increase their nightly sortie rate. The only way to do this was to double up some of the missions. For several months, the crews flew from Iwakuni to their patrol sectors in North Korea, completed their mission, and then flew to K-2 Airfield in Taegu, South Korea. Landing a B-26 at night at Taegu was no easy feat because the pierced-steel planking on the runway had begun to deteriorate. The B-26s landing there tore up dozens of tires, and more than a few accidents resulted. Also, the tires were in short supply, so each one lost at K-2 was hard to replace. If the B-26 crews got down at Taegu without incident, they could find a place to grab a quick catnap as their planes were readied for the next mission. About an hour later, they were airborne and heading north to their next target area. Four hours later, utterly exhausted, they were back in Japan, after up to ten hours of flight and combat."  Welcome to K-2 (Taegu Air Base) Welcome to K-2 (Taegu Air Base)

Click to enlarge

(Courtesy of Craig Hinton)Chinese Spring the Trap (2 Nov 50) On November 2 Peng sprang the trap to wipe out the U.S. 2nd Division. By November 5 MacArthur, without consulting Washington (but later approved by Truman), gave the orders to bomb the Korean end of the Yalu River bridges. He now realized that the Chinese intervention was serious, for the Chinese had driven Eighth Army back across the Chungchon River.

The Chinese had annihilated 15,000 of the ROK & UN forces and foiled MacArthur's plan to occupy all of Korea by Thanksgiving. But then suddenly the Chinese withdrew back across the Yalu on November 7. By suddenly withdrawing, Mao guessed that MacArthur, assuming he had beaten the Chinese, would push his troops farther north. MacArther fell for the trap. Between November 10-24, X Corps advanced toward the Yalu River in the east, while the Eight Army closed in on the west.

On 18 November 1950, B-26's from the 3d and 452d BGs flew from Japan to drop incendiaries on enemy troop barracks at Masan in far northeastern Korea. This raid was the first massed light-bomber attack of the Korean war, and it successfully destroyed at least 75 percent of the barracks area.

The Chinese simply waited to spring the trap, then on November 25 the slaughter began. Three Volunteer armies suddenly attacked the western front of Eighth Army along the Ch'ongch'on River. The ROK II Corps was in disarray after both its divisions collapsed. The road to retreat was jammed.

At the Chosin Reservoir, eight Chinese Volunteer divisions lay in wait for 1st Marine and 7th ID. On November 27 the Chinese struck and the rest is history. The debacle, the misery, the heroism, the fighting and the frozen retreat.

General Walton Walker of the Eighth Army ordered a general withdrawal of the Eighth Army -- in order to save his men. By November 28 MacArthur woke up to reality and authorized Walker to fall back to Pyongyang and there to go on the defensive, while X Corps was to withdraw to the Hungnam-Wonsan area.

The wing flew medium level bomb runs, low-level attack, and night intruder missions at the maximum range for the B-26 covering the 8th Army withdrawal. The 3rd Bombardment Group flew close air support night missions in support of the 25th Infantry Division, which was being attacked by Communist forces. The B-26 crews arrived within 30 minutes of being notified and strafed within 50 yards of the front lines of an Infantry company under attack.

Elsewhere, the B-26 crews flew their first "Tadpole" sorties, dropping bombs 1,000 yards of the front line. According to the 3rd Wing site, "The 3rd Bombardment Wing began limited operations using tactical air control posts to control (TACP) night intruder missions. The 502nd Tactical Control Group had established TACPs behind each Eight Army corps area to provide radar direction to B-29 and B-26 crews using the AN/MPQ-2 directional radar. Ground controllers acquired the bombers on the narrow beam radar and specified speed, heading and altitude. The controllers gave the orders to open the bomb bay doors and arm the bombs. At about 10,000 yards from the target, they began a countdown to zero at which time the bombardiers released the bombs. The Eighth Army provided the target list and coordinates. Its units reported good results from the so-called "Tadpole" missions. One veteran recalled that a B-26 crew usually received a "Tadpole" mission when the weather was bad and there was no place to drop the bombs visually. The missions were generally flown at around 16,000 feet. While the winter weather caused discomfort, the sorties were much safer to fly."

The extended range from Iwakuni caused numerous mechanical problems. According to the 3rd Wing site, "Mechanically the aircraft often had to land at Taegu (K-2) Korea for refuel on the return mission. They also experienced a high rate of spark plug failure due to the low RPM range used to extend the fuel range enroute to the target. The winter weather caused icing problems, which also severely hampered mission effectiveness, and flight crews began suffering mild cases of frostbite. Additional cold weather gear solved this problem. (Hist, 13BS, Nov 50, p. 2.)"

The 3rd BG began staging 16 of its B-26s along with maintenance from Taegu (K-2). Although this caused considerable logistical problems, the benefit of being closer to the targets and the increased sortie generation rate far outweighed them. This allowed the group to depart Iwakuni, fly a mission, land at K-2 and them have a replacement crew launch another mission and return to Iwakuni.

Chinese Drive South In December 1950, the Communist forces continued their drive southward, trapping the 1st Marine Division in the Chosin Reservoir area and forcing it to fight its way out to the port city of Hungnam on the east coast. There, it joined other American and South Korean units in evacuating North Korea by ship in mid-December. In western Korea, Communist forces pushed the Eighth Army across the 38th Parallel.

The Far East Air Force flew interdiction and reconnaissance missions that helped slow the enemy's advance. When, the Chinese forces attempted to move at daylight north of Pyongyang in their pursuit of the Eighth Army, the Fifth Air Force struck, killing and wounding an estimated 33,000 enemy troops. The Chinese switched back to moving at night.

According to the 3rd Wing site, "December weather and severe icing conditions hampered B-26 operations. The Invaders assigned to the group were not equipped with the "hot wing," and field modifications were not practical. In addition, de-icing chemicals and products proved ineffective due to the high speed of the B-26. Many aircraft had to abort prior to reaching the target due to icing conditions. No aircraft were lost based solely on icing problems; however, aircraft were lost for unexplained reasons in conditions prevalent to icing. (Hist, 3BG, Dec 50, Ops Ch, p. 3.)"

The Communist forces continued their advance in December. On December 5th, the UN forces were driven from Pyongyang and on 25 December, the Communists crossed the 38th parallel. The Communist forces advanced to a position roughly 50 miles South of the 38th Parallel where U.N. forces stopped them on a line that ran from Pyongtaek on the west coast to Samchok on the east coast. On 25 January, Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway, who had replaced General Walker as Commander, Eighth Army, when the latter was killed in a December jeep accident, launched the first U.N. Counteroffensive. By now the Communist forces were worn down and their supply lines overextended and under constant air attacks.

On 1 December 1950, as part of a reorganization of the Fifth Air Force, the 6133rd Tactical Support Wing at Iwakuni was inactivated and the 3rd Bombardment Wing was administratively moved from Johnson Air Base to Iwakuni Air Base where it rejoined the 3rd Bombardment Group and assumed responsibilities of base functions. Colonel Virgil L. Zoller assumed command of the 3rd Bombardment Wing, replacing Colonel Donald L. Clark.

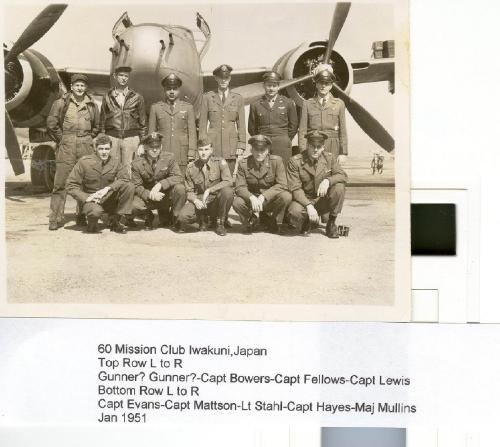

According to the 3rd Wing site, "Weather, lack of trained personnel and shortage of supplies hampered operations during the month. The B-26s were not equipped for winter operations and experienced icing problems. Due to a shortage of navigators, observers were pressed into service to provide another set of eyes for the pilot. Additionally, there was no set policy on how many missions needed to be flown before a crew member could be assigned to less dangerous duties. (Hist, 3BG, Jan 51, Ch 4, pp. 2-3.) The 8th Bombardment Squadron possessed an average of 16 aircraft, the 13th Bombardment Squadron had 17 B-26s, and the 731st Bombardment Squadron had 10 aircraft. (Hist, 3BG, Jan 51, Material Maint Sec, p. 2.)"

In January 1951, technicians began installing SHORAN (short-range navigational system) and the 3rd BW began training personnel in its use. However, it was proven that the ground based AN/MPQ-2 radar used by the Tactical Air Control Post provided better target definition and increased accuracy. Regardless, in February 1951, the first combat SHORAN mission was flown. By the end of March, combat missions had increased to 12 per night.

On 4 January 1951, Chinese Communist forces occupied Seoul. According to the 3rd Wing site, "The 3rd Bombardment Wing increased its operational tempo. In the past, B-26 crews would fly to the target from Iwakuni, then land Taegu, spend the day resting there before returning to Iwakuni. The new plan required them to turn around at Taegu after the night mission and fly a daylight mission before returning to Iwakuni. The new operational commitments required the 3rd Bombardment Wing to fly approximately 38 sorties per day, while experiencing a high loss of aircraft and an insufficient number of replacements. Weather and icing continued to plague operations. The wing was heavily committed during the month and flew missions as far north as the Yalu River. (Hist, 3BG, Feb 51, Ops Ch, p. 3.)"

Starting in the spring of 1951, the 3d Bomb Group was charged with night interdiction. Targets for their nocturnal missions included road crossings, rail lines, truck and vehicle convoys, and troop concentrations. Occasionally, airfields were also attacked. When the first interdiction effort of the year began, the 3d Bomb Group pioneered night intruder tactics through painful experimentation. It tried all sorts of "wild" ideas as tactics were worked out and optimal ordnance loads and types of bombs were determined. They tried dropping roofing nails and "tetrahedrons" (similar to jacks) to puncture truck tires...bad ideas. Finally they settled on things like the 500-pound "butterfly bomb" (similar to "cluster bombs") with bomblets that lay on the road until detonated by passing trucks.

Initially, when the 3rd Bombardment Wing began flying night missions as far north as Sinanju on the Yalu River, the enemy vehicle drivers had kept their headlights on. With experience, they learned to shut them off, making locating and attacking targets difficult.

In January 1951, crews of the 3rd BW tested using C-47 "Lightning Bug" transports to drop U.S. Navy Mark VIII flares over targets north of Seoul. Previously M-26 parachute flares had been used, but proved unreliable. Based on the result of several nights of operation, the 3rd Bombardment Wing had six C-47 aircraft modified for flare operations in February 1951. One C-47 was generally employed with two B-26s and acted as the control plane. This allowed the crews to concentrate on their low level bombing of an illuminated target. It also assisted artillery units in identifying targets at night and kept enemy movements at night to a minimum.

On 10 February 1951, Eighth Army forces captured Kimpo Airport and the port at Inchon. The forces continued north, bypassing Seoul.

According to The U.S. Air Force in Korea (pp325-326), during the early months of 1951, the 5AF "usually required the 3d Wing to fly 38 sorties each night, an effort which could include ground-radar controlled strikes against fixed targets, ground-support missions, as well as intruder sorties. The 3d Wing staged all its missions through Taegu Airfield, a practice which was not entirely satisfactory since communications with Iwakuni were poor, gasoline and bombs were often in short supply at the forward base, and the deteriorating pierced-steel plank runway at Taegu shredded critically short B-26 tires. In the ground emergency, beginning on 23 April, the Fifth Air Force required the 3d Wing to fly 48 sorties each night, and the wing met the requirement by using each aircraft for two sorties a night from Taegu -- one intruder and a second ground-support sortie."

"Intruder crews of the 3d and 452d Wings varied their tactics according to the model of planes they flew, the terrain they flew over, and the availability of natural or artificial illumination. Even if an intruder crew had flare support, Korea's rugged terrain hazarded low-level operations. Since aerial charts were frequently inexact, B-26 crews usually pulled up from strafing attacks at altitudes not less than 1,000 feet higher than the highest published height of terrain features in the vicinity of a target. One pilot further added that the "safe" pull-out altitude was actually 1,000 feet higher than the published altitude of the highest obstacle, plus an additional 500 feet for each married man on the crew. When night-intruder crews could secure flare support, they could work closer to the ground."

The book (p326) also stated, "To find answers to certain problems which are peculiar to night-attack operations, " stated Colonel Virgil L. Zoller, commander of the 3d Bombardment Wing, "we have often groped as we have operated in the darkness." The tactics employed by the 3d Wing intruder crews were influenced by the rough and mountainous terrain of North Korea, where changes in weather made positive identification of landmarks difficult and low-level attacks hazardous. Intruder tactics were also influenced by Communist actions, which varied according to their straits for supplies up forward. And, of course, intruder attack methods were different on moonlight nights, when Communist vehicles ran without lights but trains, which never used lights, could be spotted. The degree of natural illumination thus influenced intruder attack. In addition to all these factors, the night-intruder crews also experimented with "wild ideas" which might, or might not, pay off in terms of destruction to the enemy."

It continued, "Fundamental to any understanding of night-intruder tactics employed in Korea, however, is the recognition that the night-intruder crews, who flew alone in the dark, were unable exactly to determine what damage they were inflicting on the enemy. The Fifth Air Force counted automotive equipment destroyed if it exploded or burned violently or left the road at high speed and collided with some other object. Railroad equipment could be claimed as destroyed if it exploded, burned intensely, or was derailed in an area where recovery was doubtful or improbable. But in the dark night-intruder crews were seldom able to score the results of their strikes in such positive fashion. Lacking an ability to assess, the night intruders could only hope that the tactics they used were the right ones."

It further stated (p459), "Although the night intruders were undoubtedly more effective than usual against the streams of Communist vehicles which jammed the roads in the autumn months of 1951, it was all too evident later on that claims of the night-intruder crews were exaggerated. Flying alone at night, unable to secure photographic verification of their claims, the night-intruder crews were understandably unable to determine the exact results of their missions. Apparently several factors determined the extent of claims turned in by night-intruder crews. As early as September 1951 some Fifth Air Force operations analysts noted that night-intruder crews did not indicate that any one type of bomb was better than another for destroying hostile vehicles and suggested that crews were claiming vehicles destroyed in proportion to the number of vehicles sighted and the number of B-26 sorties flown. General Weyland also attributed the increased night-intruder claims of August and September to the fact that the B-26 wings were flying more night-intruder sorties than ever before. The number of Communist vehicles sighted showing headlamps had some correlation with night-intruder claims, for B-26 crews to some extent measure the success of their missions in terms of the size of the enemy convoy sighted and attacked."

According to The Three Wars of Lt. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer, His Korean War Diary, edited by William T. Y'Blood, 1999, (p355) gives a clue to the type of munitions they used. General Stratemeyer stated, "The 3d Bomb Group is in immediate need of 260 lb frag bombs. They like to use them on practically every mission. Action will be taken and a letter prepared for my signature to Colonel Zoller, 3d Bomb Wing commander, giving him all necessary information on their arrival." It continued that about a visit to Iwakuni on 16 January 1951 (p393). Gen Stratemeyer stated, "...then proceeded to Iwakuni where we were met by Colonel Zoller and his staff; listened to his briefing of the officers for the night missions which was conducted by Major C.C. Hill, my former pilot. General Vandenberg appeared to be extremely well pleased what what he saw -- and with the operations of the 3rd Bomb Wing."

Praise for the efforts of the 3d Bomb Wing (and other B-26 wings) was unanimous. However, in February 1951, Lt. Gen. Stratemeyer was concerned about the attrition rate of the B-26s due to combat losses. According to The Three Wars of Lt. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer, His Korean War Diary (p412), "Light bomb units of my command are severely reduced in combat effectiveness thru lack of aval acft. Present auth(orization) is 112 UE (unit equipment) B-26s. We have recently asked that this be increased to 144 to provide 24 UE acft per sq. This requ was based on the fact that the B-26 has proven to be our best day-night support-interdiction weapon. The increase will considerably enhance our combat capabilities. At present we have a total of 110 B-26s in FEAF, of which 16 are ineffective in FEAMCOM. ... We are losing 6 B-26s per month in operations. ... Delivery of B-26s must be advanced if our rqmts are to be realistically met."

However, the B-26's that were sent were "shocking disappointments." According to The U.S. Air Force in Korea (p461), "Some of the old planes still had "flat-top" canopies, which disqualified them for combat since crewmen who wore winter flying equipment and survival gear could not squeeze out of them in bail-out emergency. Even with the nonstandard B-26's, moreover, USAF ultimately had to recognize its inability to bring the 3d and 452d Wings up to war strength. In the spring of 1952, a final USAF programming action allocated 24 B-26's to each 3d Wing squadron and 16 B-26's to each 452d Wing squadron."

It continued, "The supply of B-26 replacement crews was also deficient. Geared to produce 45 crews every 5 weeks, the combat crew training school at Langley Air Force Base could not satisfy FEAF's attrition and rotation requirements which went from 58 crews a month to 63 a month, and then to 93 a month in the last half of 1951. USAF had to obtain the additional crews by levying on zone of interior commands for casual crew personnel who were formed in crews for training in the Far East."

In May 1951, the Chinese launched the Fifth Chinese Campaign in which the Chinese suffered a major defeat with 17,000 dead and 10,000 captured. With the Chinese no longer capable of mounting another major offensive, Mao ordered his troops to turn the war into one of sheer endurance. The Chinese were used to guerrilla warfare and were not used to tunnels and trench warfare.

On May 31, 1951, the negotiations began -- shakily at first because of the insistence on it being held at Kaesong in North Korean territory. General Ridgeway told the JCS he would refuse to attend at Kaesong -- even if directed. However, finally it was agreed to hold it at Panmunjon.

At the outset of the Korean conflict the 3rd was at two Squadron level (8th BS and 13th BS) with the 731st Bomb Squadron (L-NA) from the USAF Reserves attached to it. On June 25, 1951, the 731st was redesignated the 90th Bombardment Squadron (Light - Night Intruder) and absorbed all aircraft and personnel of the 731st. Simultaneously, the 731st Bombardment Squadron was inactivated.

In June, Captain Heyman of the 8th Bombardment Squadron became the first 3rd Bombardment Wing B-26 pilot to score an air-to-air victory in shooting down a "flying bathtub" -- a Papov Po4 heckler commonly called "Bed Check Charlie."

In June 1951, Detachment 1, 3rd Bombardment Wing, stationed at K-2 (Taegu), inactivated and all personnel and resources were sent back to Iwakuni AB, Japan or K-8 (Kunsan), the future home of the wing. A primary reason for discontinuing operations from K-2 came from a critical shortage of tires for the B-26. It was noted that the poor conditions of the K-2 runway, notably the steel planking, caused considerably higher tire failure rates. In one 10-day period at K-2, 56 tires required replacement. (Hist, 3BG, Jun 51, Ops Section, p. 2.)

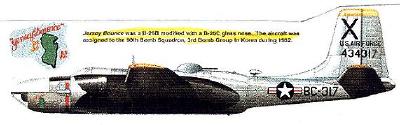

The truce talks began on July 10, 1951...and the war dragged on...and on...and on. The deadly accuracy of the 8th was soon felt by the enemy as more and more trucks and locomotives were destroyed and the main supply routes to the Communist front lines became hazardous for daytime movement of troops and equipment. The enemy was soon forced to camouflage their trucks by day and move only at night. The versatile 8th countered this move however. On June 25, 1951 the 8th was redesignated as the 8th Bombardment Squadron (Light, Night Intruder).  | "Jersey Bounce was a B-26B modified with a B-26C glass nose. The aircraft was assigned to the 90th Bomb Squadron, 3rd Bomb Group in Korea during 1952." Jack Barclay added, "As I recall this aircraft was transferred to the 90th BS and I think they lost their CO in it. Aircraft still has 8th BS colors on fin and wing tip and horizontal stabilizers." (From A-26 Invader in Action by Jim Mesko) |

Mike Voskian with Jersey Bounce. (Courtesy Larry Caseria)

Larry Caseria added, "Mike Voskian. You will find him in the supply section. He originally worked for me (engines) but transferred to supply right after Lt. Schmidt and I took Mike for a ride. He had never flown so we took him on a check ride and let him fly in the nose so he would have good visibility. It turned out to be a traumatic experience for him and never wanted to be around airplanes again. He would actually get physically ill when he heard the airplanes running so we had to remove him from flight line duty." |

Staged ordnance photo during Korean War shows 100-pound bombs, four scuffed napalm tanks, and around 6,000 rounds of .50-caliber ammunition. Pilot Lt.Col. Joseph Belser, left, and Sgt Alfred Head, crew chief, both from the 3rd Bomb Group, posed for the photo. (Bowers collection) |

After the mammoth Chinese drive was stopped short of Seoul and the Communists were steadily driven northward again. Only a Chinese request of "peace talks" and international politics halted the United Nations advance in June of 1951. With the details arranged, armistice talks between U.N. Command and NKPA/CPVA representatives begin at Kaesong on 10 July 1951. U.S. Adm. C. Turner Joy headed the U.N. delegation. From the start there were problems when the NKPA/CPVA barred UN Press teams and Adm. Turner walked out. Later the press was allowed in.

On 23 July, the Far East Air Force, accompanied by naval aircraft, launched a massive air strike against North Korea's hydroelectric power grid, causing a blackout that lasts for almost two weeks. Results of the air strike extend into northeast China, which loses almost 25 percent of its electrical power. On 27 July, the negotiations reached an impasse when Nam Il, the chief delegate for North Korea, lost his temper at a U.N. proposal that the military demarcation line be based on the present battle lines. On 30 July in order to keep pressure on the communists, Gen. Ridgway ordered massive air attacks on Pyongyang, the North Korean capital. Four hundred forty-five planes hit the city. The AFHRA stated "July 30: In the largest single mass attack for the month on targets in the Pyongyang area, ninety-one F-80s suppressed enemy air defenses while 354 USMC and USAF fighter bombers attacked specified military targets. To avoid adverse world public opinion during on-going peace negotiations, the Joint Chiefs of Staff withheld information on the strike from the news media." The entire 3rd Bomb Wing was involved in this push that included every available USAF fighter bomber from the 8th FBW along with USMC support from the 1st MAW.

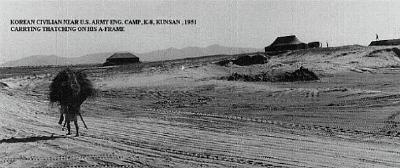

Move to Kunsan AB (K-8) (Aug 1951) As the peace talks at Kaesong dragged on through July and August, the 3rd Bomb Wing moved to Korea to be nearer its targets. On 18 August 1951, the Squadron moved to Kunsan, Korea under the command of Lt. Col. Stanley V. Rush. While the front line positions remained stagnant, the 8th flew hundreds of missions to hamper the Red efforts to build up their supplies in order to recover from their ill-fated Spring offensive.  Korean Laborer at K-8 near the 808th Engineering Aviation Battalion (SCARWAF) (1951) Korean Laborer at K-8 near the 808th Engineering Aviation Battalion (SCARWAF) (1951)

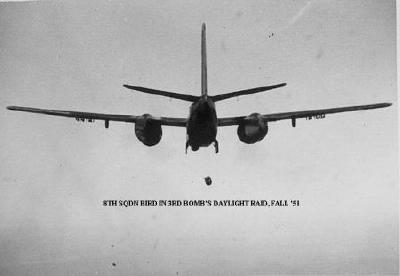

(Courtesy Al Gould)At first the 8th's efforts were confined mainly to night route recce's (reconnaissance) although bomber streams, rail recce's and daylight formations were used effectively. With the solidification of the front line, a new kind of bombing came into being. The "tadpole," striking at enemy front line positions protected by weather or darkness, hit with such uncanny accuracy that the Chinese and North Koreans developed a mystical fear of the "planes that can see in the dark."  Rare Daylight Mission from K-8 (1951) Rare Daylight Mission from K-8 (1951)

(Courtesy Al Gould)

Click on photo to enlarge |  Rare Daylight Mission from K-8 (1951) Rare Daylight Mission from K-8 (1951)

(Courtesy Al Gould)

Click on photo to enlarge |

Lt.Col Wilson returning from Day Mission (1951) Lt.Col Wilson returning from Day Mission (1951)

(Courtesy Al Gould)

Click on photo to enlarge

Douglas B-26 Invader The A-26 was developed from a 1940 Army Air Forces request for an attack aircraft to replace the A-20, B-25 and B-26 Marauder bombers then entering service. Drawing heavily from their A-20 Havoc design, Douglas built three Invader prototypes to fill the light bomber, night fighter and attack roles envisioned by the Army. The first of these, the XA-26 light bomber variant, flew on July 10, 1942.

The A-26A never made it to the production line. Although the flight trials were successful, the XA-26A was never put into production, since the Northrop P-61 Black Widow night fighter which had already been put into production had a similar performance and was deemed to be adequate to meet the USAAF's needs.

Two Invader models were built; the A-26B had a six- or eight-gun nose, while the A-26C used a glass nose for a bombardier or camera equipment. The first 500 A-26B models were built at the Douglas plant in Long Beach, California, while another plant in Tulsa, Oklahoma built most of the 1,091 A-26Cs delivered. Frustrating production delays due to a lack of tooling, project engineers, poor communications and numerous change orders prevented the plane from entering service in mid-1943, as had originally been planned.

Invaders entered World War II in mid-1944, when four were evaluated by the 5th Air Force in the South Pacific. With a top speed approaching 400 mph, the A-26 was the fastest U.S. bomber of the war. The A-26B flew into combat on November 19, 1944, with the 9th Air Force in Europe, and deliveries to Pacific-based units soon followed.

The 8th Bomb Squadron conducted the first combat trials of the A-26B in May-June 1944. After conducting local tests, the unit flew the aircraft on combat missions. However, due non-availability of military targets, the full capabilities of the A-16 were not tested. According to the Monthly Unit History, 8th Bombardment Squadron (L), June 1944, Part I Chronological Narrative, "THE A-26B - COMBAT TRIALS" it stated: The pilots were greatly disappointed with the A-26Bs, which received considerable testing in combat during June. Unfortunately they did not run into any really good shipping or grounded aircraft targets, but average targets of this theater were attacked.

Capts. Greene and Gordon and 1st. Lt. Shook were checked out and flew the A-26s as nearly as good a plane for low level attack as the A-20. They thought it would be good for medium bombardment and excellent as a "Fat Cat".

The principal drawback was the extraordinarily poor lateral visibility caused by the projecting engine nacelles. Visibility to the sides during a barge search or on attack is practically nil. The forward vision also is considerably restricted, compared to the A-20. This feature alone was felt to count the A-36 completely out for low level attack on average targets in this theater.

Another disappointment was the short range -- not exceeding that of an A-20; also the cruising and maximum speeds were considerably under what had been expected. On the advantage side were the terrific forward firepower (3500 X .50 cal. expenditure, or 1 1/2 to 2 times that of the A-20, being usual on strikes), the large bomb load, the comfortable cockpit and ease of flying, combined with the ability to carry a navigator, crew chief or observer, without crowding. In June 1948 the A-26 was redesignated as the B-26, after the similarly-designated Marauder had been retired from service. Although obsolete, the Invader distinguished itself in the night interdiction role in Korea, and flew the first and last USAF bombing missions of the war. The highly versatile plane was used for bombing, reconnaissance, transport, and night interdiction, primarily with the USAF's 3rd Bombardment Wing.

The following 1993 article tells how the Douglas Aircraft Corporation's A-26 Invader was renamed to a B-26 Invader, forever after causing confusion with the Martin Aircraft Corporation's B-26 Marauder, a nearly the same size and shape medium bomber. There is no such thing as a "Douglas B-26 Marauder" -- but many in the press started causing this misnomer. The article was written by John Moench, M/Gen, USAF, Ret, who is also the author of Taking Command -- a novel about how Kunsan AB had degenerated into a low-class backwater hell-hole by 1959 after the 8th Bombardment Squadron (L-NI) had departed. The article was excerpted from the March Field Museum website."THE MARAUDER" VERSUS "THE INVADER"

By Major General John 0. Moench (August 1993)

I think it's about time the truth is known. I write this in appreciation of the fact most of the persons of the time of the decision to rename the A-26 as the B-26 have now "Gone west" or are disinclined to engage themselves in thoughtful process.

In retrospect, it was a most unfortunate quirk of history that caused the A-26 "Invader" to become the B-26 "Invader". How did this all happen? Was there a sinister plan behind the renaming --- a plot? Was it, as many have suggested, something "diabolical" --- or was it really an unfortunate event? Here is the story.

As I recall, the year was 1949. The new Air Force was still an organization not fettered with all the rules and regulations of the U.S. Army and the hierarchy was determined that it would never be so burdened. For anyone serving in today's Air Force, this resolution supporting "simplicity" may fall on very deaf ears. But, at the time, we operated mostly with blank sheets of paper to which, as needed, we applied a minimum of wordy, ironclad rules and regulations. Decisions were made by individuals --- many of them as junior as I --- and generally with minimum protocols, staff study and definition.

Following World War II, at the ripe age of twenty-four, I went directly to the Air Material Command at Wright-Patterson and took over the production control of all the United States Depots in the Continental United States and more. Then, after three years there, I found myself in charge of aircraft maintenance in Air Force Headquarters. Don't ask me how this all happened --- it just did.